'What kind of poem would you make out of that?'

A review of 'Coal Mountain Elementary'

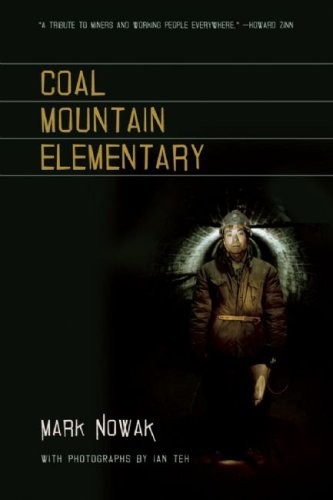

Coal Mountain Elementary

Coal Mountain Elementary

“What do you think are some of the costs associated with mining coal?” This quote from the American Coal Foundation appears in Mark Nowak’s Coal Mountain Elementary, which I happened to read in the days following the Deepwater Horizon explosion in 2010. Reading the book during the worst environmental disaster in US history, I couldn’t help but also ask: What are some of the costs associated with offshore oil drilling? For that matter, what are the costs associated with any industry? And by “costs,” I’m not just talking about what we hand the cashier for a tank of gas.

If you ask the person in the street what they know about the costs of energy—economic, environmental, human—chances are they can tell you very little. Whatever interest there is in discovering the actual costs of energy production seems to surge after news of some crisis— a mine collapses, an oil rig explodes—only to ebb after rituals of public apologies, committee hearings, promises to review industry regulations, and so on.

And then it’s back to business as usual.

One way to increase and sustain consumer consciousness is to provide media that explore the costs associated with business as usual, and to this end we’ve seen a trend in recent years toward critical investigative reporting on industries such as coal and oil in nonfiction books, documentary films, newspaper and magazine exposés, and blogs.

And what about poetry?

In his essay “Investigative Poetry” (1976), Ed Sanders emphatically states that poets should “NEVER HESITATE TO OPEN UP A CASE FILE EVEN ON THE BLOODIEST OF BEASTS OR PLOTS.”[1] Coal Mountain Elementary makes an excellent case-file contribution to the tradition of investigative poetry, taking as its point of departure the coal mine explosion on January 2, 2006, in Sago, West Virginia, which killed twelve miners. Readers may recall not only the deaths of these miners, but also the miscommunication to family and media that these miners had been rescued. But the Sago mining disaster is only one of the stories in Nowak’s book. Unlike more traditional investigations that focus on a particular case or event, Coal Mountain Elementary is a collage of first-person testimony from the Sago Mine Accident Report and Transcripts (SMART), news reports of mining disasters in China, “lesson plan” materials from the American Coal Foundation (ACF), photos of Chinese mine workers from Ian Teh, and the author’s own photographs of American mining towns. I would add to this list Nowak’s blog at coalmountain.wordpress.com, an ongoing chronicle of mining disasters that reminds the reader that the story of coal mining’s devastating impact on human lives and communities isn’t finished. Among other things, the book’s multimedia approach encourages the reader to critically reflect on the coal mining industry beyond national, cultural, and historical boundaries.

Before even opening the book, the chthonic, coal-colored cover tells us that we are going down into a dark place to learn something elementary, elemental, and primary. A miner stands in this darkness, an arc of light gilding the tunnel wall behind him, and stares directly at the reader. The book’s title, in jagged script as if pick-axed out of rock and laid out on what appears to be lined school paper, announces a curriculum of coal. The educational motif extends to the book itself, which is divided into four sections: three “lessons” and a coda. Each of the first three sections is organized around text from one of three ACF “lesson plans”: “Coal Flowers: A Historic Craft,” “Cookie Mining,” and “Coal Camps and Mining Towns.” As noted in the “Works Cited,” these lessons were created “to develop, produce and disseminate, via the web, coal-related educational materials and programs designed for teachers and students” (179). A visit to the ACF website reveals that the foundation is supported in part by “coal producers and manufacturers of mining equipment and supplies” and that the lesson plans were created for K–12 students. Aside from the corporate sponsorship of education, there is nothing particularly suspect about these lesson plans for children. Within the classroom of Coal Mountain Elementary, however, the curriculum takes on an ironic and somewhat surreal tone. In “Second Lesson: Cookie Mining,” for example, “Students participate in a simulation of the mining process using chocolate chip cookies and toothpicks. The simulation helps to illustrate the costs associated with the mining of coal” (65). From the “PROCEDURE” section of the lesson:

1. Review the costs

associated with coal mining:

land acquisition, labor,

equipment, and reclamation.

Coal companies

are required by federal law

to return the land they mine

to its original, or an improved, condition.

This process, known as reclamation,

is a significant expense for the industry. (94)

On the opposite page, we read the following news report:

An explosion tore through a coal mine in northern China on Wednesday, leaving at least 62 workers dead and another 13 missing, the government said, the third disaster in recent weeks involving scores of miners. The latest accident highlights the Chinese government’s continuing battle with mine safety despite repeated crackdowns and pledges by the leadership to improve conditions. Wednesday’s explosion occurred at the run Liuguantun Colliery in Tangshan, a city in Hebei province, when 186 miners were underground, said an official with the Tangshan Coal Mine and Safety Bureau who would only give his surname Zhang. Zhang said 82 minders escaped on their own and 32 were rescued, but three of those later died. The bodies of 59 other miners had been recovered by early today and rescuers were searching for 13 people still trapped in the mine. (95)

As the news report makes clear, there are more “costs / associated with coal mining” than the lesson plan reveals. Coal is not chocolate; there is no reclamation for the dead. But more is going on here than factoring the total costs of mining coal. In addition to its critique of the coal mining industry, Coal Mountain Elementary may also be read as a critique of pedagogy, including US standards of education and corporate involvement with curricular development. I also see an implicit critique of metaphor as an educational and literary tool. In the first lesson, students transform coal into “flowers,” and in the second lesson, cookies substitute for mountains, chocolate for coal, and toothpicks for mining tools. Of course, metaphors have the potential to expand consciousness and make deeper ethical connections between ostensibly disconnected subjects, objects, experiences, and ideas. Within the context of news reports and testimonies of mining disasters, however, the metaphorical comparisons and substitutions of these lesson plans tend to conceal more than they reveal, ornamenting and sweetening the prosaic and bitter story of coal. Coal Mountain Elementary relies not on metaphorical comparisons but on metonymy’s spatial contiguities among juxtaposed texts. It is a readerly text: the reader must make connections between decontextualized documents, instead of relying on the writer to make them. For instance, the above news report of a coal mine disaster neither transforms nor substitutes for the previous lesson plan. Instead, the report provides a new context or container for reading the lesson plan, which forces the reader to revisit the question: what are the costs associated with coal mining?

Reading news reports and testimonies of government subterfuge, out-of-touch mine owners, and bureaucratic bungling, it is tempting to simply deride the naïveté of these lesson plans in order to process feelings of sadness and rage over the destroyed lives that we encounter in the book. But to scapegoat the ACF curriculum does nothing to engage the deeper social, political, historical, environmental, and economic realities of the coal mining industry. Any possibilities for irony’s distancing and derision begin to recede in “Coal Camps and Mining Towns,” which draws on a lesson plan that is less metaphorical and more attentive to material realities: “Students look at the history of the coal mining industry by researching coal mining towns” and “write short stories that highlight the people who lived in coal communities” (135). What also makes this section more effective is how the lesson plan aligns more closely with what Nowak is doing with the materials at his disposal: investigating language, history, origin myths, communities, and individual lives.[2] Here is a section from the “Coal Camps and Mining Towns” lesson plan:

NATIONAL STANDARDS:

National Council for

the Social Studies

Standards: Culture;

Time, Continuity,

and Change;

People,

Places, and

Environment.

National Council

of Teachers

of English

Standards:

Students

employ

a wide range of strategies

as they use different

writing elements

to communicate

with diverse audiences

for a variety of purposes. (144)

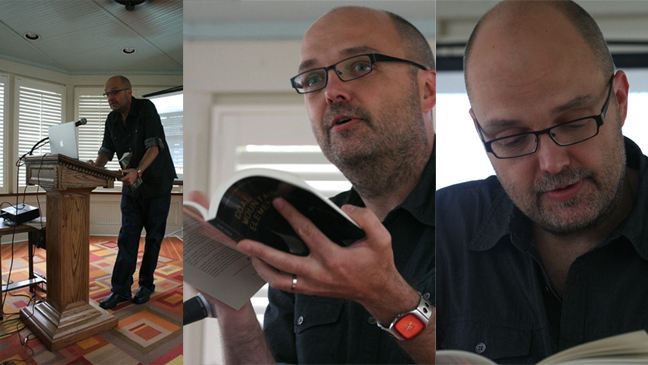

Mark Nowak reading from Coal Mountain Elementary at the Rose O'Neill Literary House, all images ⓒ Karly Kolaja

Compare the adjacent passage taken from the Sago Mine Accident Report and Transcripts:

I’m going to tell you, the only thing—carrying Mr. McCloy out, I was on the right-hand side in the back, close to his head. And what I was doing, and we all were doing it, we were talking to him all the way out. Hang in there, we’re going to get you out. And I put myself, my eyes on his hand, and I noticed he had a wedding band on, and I’m thinking about this young man. And I watch his hand all the way out to see if he moved any, and that’s what I did. I was watching to see if I could see any movements. But I did notice his wedding band on his hand. He never did move his hand that I could see. (145)

An abrupt tonal shift moves us from the generalized language of the lesson plan (“Time,” “Continuity,” “Change”) to first-person testimony in which the particular detail of a wedding ring becomes a focal point in this miner’s life and the life of the narrative itself. Within the original context of the Sago hearings, these recollections were most likely passed over as immaterial, but for those who knew Mr. McCloy, these memories of material details undoubtedly communicate what Nowak calls “a variety of purposes.”

*

Johannesburg Mines

In the Johannesburg mines

There are 240,000

Native Africans working.

What kind of poem

Would you

Make out of that?

240,000 natives

Working in the

Johannesburg mines.

—Langston Hughes[3]

In a blog post titled “Poetics (Mine),” Mark Nowak points to Langston Hughes’s “Johannesburg Mines” as an example of a poem that “works in divergent fields that make parallel (and antithetical) critiques, analyses, and representations.” During a Q&A following his May 2010 reading at the Wooden Shoe Bookshop in Philadelphia, Nowak also mentioned the Hughes poem as an inspiration for Coal Mountain Elementary. I want to make a brief detour into this poem not for the obvious connection to mining, but to point up tactical affinities between the poem and Coal Mountain Elementary. The first three lines of the Hughes poem assert a prosaic fact that may have come from a newspaper, followed by a question: “What kind of poem / Would you / Make out of that?” The question is then answered, more or less, by the very fact that prompted the question: “240,000 natives / Working in the / Johannesburg mines.” Of course, much can be made of syntactical shifts and changes in diction (for example, “Native Africans” to “natives”), not to mention issues of race, class, colonization, Apartheid, labor history, and so on. But what I want to note here is that the process of receiving information, formulating a question, and then restating the information becomes the answer itself: a poem called “Johannesburg Mines.” Does this “answer” the poem’s question? What does it mean to answer the question of how to “make” poetry out of facts by restating those facts? Is the question addressed to the reader, or to the speaker himself? Does the poem imply limitations on what poetry can “make”? Does it imply some transcendence of poetry’s limitations? Is the poem a commentary on the ethical limitations of aesthetics? Is it a commentary on the ethical possibilities of aesthetics?

In Coal Mountain Elementary, facts are restated in response to an implied question which might go something like this: What kind of poem would you make out of the lives and deaths of coal miners throughout the world? As a composite of verbatim news reports, testimonies, and curricula, Coal Mountain Elementary is a matter of record: Mark Nowak did not “write” this book any more than Langston Hughes “wrote” a poem on the Johannesburg mines. But who “wrote” Coal Mountain Elementary is less interesting to me than what Nowak reveals about how we define authorship, and what we call Coal Mountain Elementary (poetry; not poetry; found poetry; documentary poetry; investigative poetry; working class poetry; labor poetry) is less interesting to me than what the book reveals about our expectations for poetry. Authorship implies a number of things, including authority, authenticity, ownership, originality, and the transformation of experience into cultural artifact, and perhaps more than any other literary genre, we expect poetry to somehow transform experience into something else. We also seem to think of poetry as a more suitable genre than, say, fiction or nonfiction prose for reflecting the private and interior experiences of the writing subject.[4]

In an era of political poetry marked by what may be called a negative rhetoric of blame, on the one hand, and an internalized rhetoric of lament, on the other, I hear in Nowak’s book both implicit praise for miners and an externalized rhetoric of the document. The very fact of including the voices of miners and rescue workers in the book is itself an act of praise as well as a desire to let those closest to the experiences speak for and as themselves. In turn, you can hear in the words of the Sago testimony transcripts the emotions that testifying calls forth, as well as the unfolding of memory in the syntax and rhythms of spoken language. What I most appreciate about Coal Mountain Elementary is its foregrounding of the document in a time when so many investigative media seem to position the author at the center of the text. In this way, Nowak’s work harkens back to earlier approaches to the document in the poetry of Charles Reznikoff (Testimony, Holocaust) and Muriel Rukeyser (The Book of the Dead), as well as the documentary style of Frederick Wiseman in his critiques of schools, hospitals, mental wards, and other institutional spaces.

Although Nowak documents the costs of the coal industry in human life and livelihood, he does not address the costs to the environment. This raises the question: What would a documentary poem on the coal mining industry’s destruction of the environment look like? One difficulty in addressing the environment through documents may have to do with the fact that we define the document as a human and cultural artifact. This definition excludes natural objects (bodies of water, flora) and subjects (nonhuman animals) that have no “voice,” let alone “personhood,” that would qualify as document in any of the traditional (i.e., anthropocentric) ways that the word is currently defined. This also raises important questions about rights, insofar as documents and the ability to document are often invested with legal significance. Although questions concerning environmental rights are absent from most cultural conversations, they are currently being discussed among legal scholars, political scientists, bioethicists, and environmental activists.[5]

Of course, each occasion demands its own form, and no single method of documentation is inherently superior to all others. Indeed, the popularity of documentary films by Michael Moore and Morgan Spurlock, as well as investigative nonfiction prose by Michael Pollan and Jonathan Safran Foer, attests to the effectiveness of using first-person narratives as vehicles for delivering compelling critiques of various industries and institutions. In Coal Mountain Elementary, however, critical and creative accountability shifts squarely to the reader, who must make her way through the materials without any overt master plot or central narrative voice for guide. Along the way, each reader is called upon to answer the question: at what cost?

1. Ed Sanders, Investigative Poetry (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1976) 23.

2. My focus here is on the more paratactic and nonlinear elements of Coal Mountain Elementary, but another way to read the book is to explore syntactical and linear elements that help to organize the book. Some of these elements include the narrative coherence within the news reports and testimonies, the chronological unfolding of both the Sago mine disaster and mining disasters in China, and the sequencing of the lesson plans that begin with activities for elementary school students (“Coal Flowers: A Historic Craft” and “Cookie Mining”) and graduate to an activity for middle- and high-school students (“Coal Camps and Mining Towns”).

3. Langston Hughes, “Johannesburg Mines,” The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, ed. Arnold Rampersad and David Roessel (New York: Random House, 1994) 43.

4. For a more detailed discussion of authorship and authority as they relate to a poetry of witness, see my essay “Poetic Representation: Reznikoff’s Holocaust, Rothenberg’s ‘Khurbn,’” in Response: A Contemporary Jewish Review 68 (1997): 129–140.

5. For an early exploration into the idea of environmental rights, see Christopher D. Stone’s “Should Trees Have Standing?—Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects” (1972), reprinted in Should Trees Have Standing? Law, Morality, and the Environment (Oxford University Press, 2010). See also the recent movement for a United Nations Universal Declaration of Planetary Rights.