'Tide in and tide out'

A review of Dean Rader's 'Landscape Portrait Figure Form'

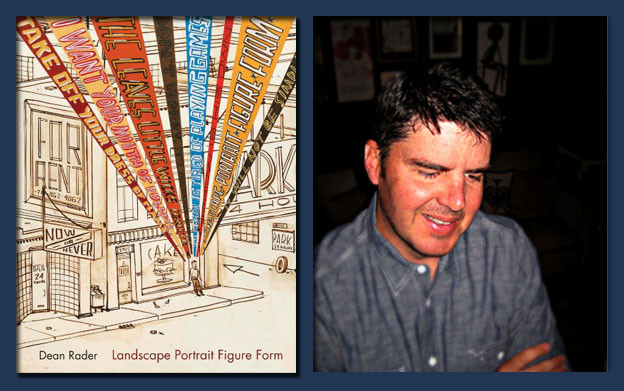

Landscape Portrait Figure Form

Landscape Portrait Figure Form

“American Self Portrait,” the poem beginning Dean Rader’s Landscape Portrait Figure Form, introduces with considerable urgency the book’s interest in living and writing deliberately as an American poet. With a mouthful of bravado, the poem speaks almost exclusively in imperatives, demanding the materials of national portraiture:

Give me the sheriff star pinned to the mermaid

and that tiny piece of wood from your throat.

Give me the saw blade, the plastic cat’s eye.

Give me the flash drive of your tongue.

I want to save everything. […] (1)

The voice swings from demanding to sensitive, greedy for the power and romance of the sheriff’s Disneyfied star and outlaw enough to steal the cross right off your necklace, to take emblems of authority along with the power and the junk. Everything is potentially precious; what matters turns on a dime, and the American impulse to “save everything,” by rescue and in storage, is as close to its drive to dispose and replace as two sides of a page. The large, unfocused desires for kitsch and carpentry, badges and baubles, and for all possible worlds and words stored up on the tongue’s flash drive articulate the complicated American vision for which Landscape Portrait Figure Form seeks form and expression.

Throughout this compressed book, Rader openly inspects the American poet and the American nation in their mutual production in a conceptual landscape very different from Whitman’s matrix of soil and soul that produced his own exquisite voice and character. In Whitman’s world, the poet could watch and wait, gather the voiceless into his lines and give them voice, stand in the middle of a throng yet stand apart from the crowd and its conversations. In the 21st century, the poet cannot imagine the isolate individuality of Whitman’s “Me myself” — or can only imagine it — nor can the poet unselfconsciously envision writing from a protected interiority undisturbed by other people and nations and their news, wants, and views. Rader’s poetry asks how to be an artist in a nation founded on and still struggling with the demand for representation and what poetry as a medium means in an era of representational sprawl.

Many poems in this collection bear “America” and “American” in title or in body, but matters of portrayal and representation, of both personal and national identity, inform every poem in the book, including those in the middle section conversing with Paul Klee’s art and theory. “Self Portrait as Wikipedia Entry,” the book’s second poem, underscores these related concerns in what begins as a joke about the current pressure nearly everyone feels to have a “web presence” and the open secret that Wikipedia is unreliable and entries easy to fake, even though it is the first source most consult (even its decriers) for information:

Dean Rader was born in Stockton, California during the Summer of Love. His sorrow is his own. He believes in star-sting and misnomer; he carries a toy whistle in his pocket. American by nationality, he was conceived in a Fiat near the Place du Chatelet. (2, links Rader’s)

Beginning with terms faithful to the traditional biographical template of birthplace and links to history, the poem moves swiftly to offset the humanist assumptions of individual specialness and achievement built into the biographical entry and encyclopedias generally. Absurd details that call attention to the ease with which one might invent facts mingle with plausible conclusions about poetic genealogy: “one of his recent poems […] suggests an influence of Simone Weil” (2-3). Notably, “Simone Weil” is not hotlinked, implying the medium’s (and Americans’) lack of interest in theology and disdain for the French.

This mixture and its mimicry of non-academic resources also imitate trends in contemporary poetry to celebrate the passing of authenticity by invoking ironically its codes. Many of Rader’s poems seem to participate in the trend to flout traditional authorities, especially and including sincerity, through a display of popular culture know-how blended with erudition, a trend that (also ironically) tends to serve the same elitist attitudes it often hopes to mock.

But I think it is a big mistake to see Rader as merely a meta-poetic self-deprecator in this poem or anywhere else, even in the cheeky blurb on the back cover. “Self Portrait as Wikipedia Entry” ends with an excerpt attributed to Rader reportedly circulating on the internet. The fragment is spare but crammed with gorgeous aural and visual images that comment on the production of writing and its capacity to sustain the fragile connections of the collective “we.” Under the pretext of a dubious citation, the fragment permits the intrusion of the sincerely playful poet’s voice, converting a busy gag about wikipedic self-importance into a sly statement about the serious matters of poetry, like facing impermanence and the inevitability of suffering:

Line up and line out

says the moonwhittle.

Loss is the ring on our finger, the bright gem

compassing every step as we drop down.

Believe in what you know and you’ll go blind.

Experts doubt its authenticity. (3)

In this closing line, the mistrust of authenticity becomes a way of authenticating the poem while stressing the tangle of functions making “authenticity” always already doubted.

Significantly, Rader’s presentation of his poetic presence as a fragment drifting at several removes works like Sappho’s fragments to keep in view the poet and poetry as both whole and part, all there is and the mark of what isn’t. “Think of me as the broken you” (31) the speaker of “Study of the Other Self: American Self Portrait II” instructs the reader through a similar image. Throughout LPFF, drifting pieces of self sometimes wander up to and sometimes forcefully direct the reader to reconsider a relationship with the poems and with language. “Study of the Other Self” ends in a devastating comment on the little, unnoticed customs that connect us, like the American idiom’s combination of word and gesture:

Believe me when I tell you

that there is nothing beyond

these words, that wall, your name —

Here, stick your arm through the bar,

I want to sign your cast. (32)

Both the abrupt undercutting of what seems the start of a nihilistic or at least atheistic argument and the childlike bluntness of the command to “stick your arm through” end this poem in a familiar (but we forget!) template of our interdependency, the ways we heal physically and socially through attention to word and body. Rader’s cast is one of several images of protective care and social glue — others include a cape, coat, mask, and umbrella — but the custom of signing someone’s cast captures best that double-sided American egotism introduced in the first poem. Signatures on a cast can seem like claims to small-time celebrity (I know someone who broke her arm!) and self-advertisement, but they are equally signs of rooting for the other guy, the broken you, to be whole again. The broken you who sticks that arm through the bar trusts the grace of the ritual, that deep contract of mutual salvation and goodwill.

In these varieties of address and presence, Rader’s work urges a model of subjectivity that recognizes both humans and their poems as parts of one another, greatly in need of ways to see and feel our contact and closeness. These “I”s and “we”s and “you”s all hunger for tenderness and intimacy. And like the faux fragment picked up by the faux Wikipedia entry, the poems link loss and lapse to the danger of thinking you know it all or that what you don’t know isn’t important, of believing you are complete. “Believe in what you know and you’ll go blind” is a warning that combines Socrates’ paradoxical notion of wisdom (knowing you know nothing) with Dickinson’s directive about truth telling, accomplished through angles and repetitions. The moonwhittle’s playful command and description of both life and writing, “Line up and line out,” warns that ignorance and arrogance, as well as rushing the Truth, all can blind — this wry warning had me thinking of Dickinson’s description of delivering truth as apt for the interwebs’ era of self and study where information and revelation occur in a constantly expanding, multidimensional Venn diagram: “Success in circuit lies.”

Success also relies on looking, thinking, and patience — circuits of attention that are active but unhurried. The fragment predicting blindness for unexamined knowledge cautions, in this context, against the urgency that comes with technological connectivity: we are conditioned to expect information promptly in forms that can be gulped down right away or stored on a convenient (and fast) drive or in the cloud, not in long, looping circuits eventually lassoing us in enlightenment. Again, reminiscent of Whitman’s self-named speaker who leans and loafs, Rader’s speakers encourage watching, waiting, and listening. In “Rush,” an epistolary poem, the speaker laments “the / unfortunate man who rushes through” (34) in a hurry to satisfy wants rather than to examine them. These poems present alternative ways of occupying our multiplying territories. Rader’s is a poetics of slowing down and of wandering. It calls for a slackening of pace and a release of destinations in order to recover the sacred elements in the world around us, not only in the waves and clouds but also in the art that, like prayer, leads us out of ourselves and alters our vision of the ordinary.

Although spiritual appetites appear throughout the book, they are most explicit in the poems about Paul Klee’s painting. “Becoming Klee, Becoming Color” describes a stripping of self so thoroughly it’s almost Donneian in its pursuit of transformative vision. The poem’s voice enters into the processes of the artist, envisioned as an opening and offering of self to the materials of art:

When he closes his

eyes he tries to want what the colors want:

the agony of onyx, the sorrow of burlywood,

the obsessions of oxblood. Over and over he

asks of the colors to find their form. (12–13)

These lines narrate the efforts towards self-abnegation preceding creation as a struggle for pure vulnerability more important than the creation itself. Pressing against the book’s meditation on American portraiture, intense study of color, and the call for color to change shape further suggest an alteration in consciousness to accompany the shifting racial palate of the contemporary United States. The poem ends in a provocative genesis of shapes and boundaries, called into being by the release of ingrained perceptual modes,

[…] ochre lune the sun and its shadow

self, a black and white incircle this

city and its roads, that instead of pushing

us out, draw us in. (14)

The opening of spiritual and topographic borders results not in chaos or abandonment, but in embrace and inclusion. Released from “colors / that are not theirs,” hidden structures extend a vision of human community established on attraction and collectivity rather than security or institutions.

In echoing Whitman’s priorities and lyric strategies, Rader’s work carries Whitman’s faith that “Americans of all nations … have probably the fullest poetical nature. The United States themselves are essentially the greatest poem” (711).[1] It also carries with that faith the disappointment Whitman described in Democratic Vistas much later in his life that the truly American poem had yet to be written and that Americans were squandering the promise of democracy in hot pursuit of capitalist frippery.[2] That irresistible structure hidden within ideas of color and order and concealed in the virtual piles of data, saved and protected but too vast ever to be interpreted, requires facing the many griefs that conceived them, like poverty, exclusion, exile, injustice, and loss. LPFF is in many ways a book about grief and its wandering, lonely states: “What is life but dark / waters washing us up? Tide in and tide out” advises “Self Portrait as Photograph Never Taken” (8). Our pains and failures are considerable, but they are not permanent — and they are not our whole story.

Facing personal and national sorrow, though, does not mean holding on to it. A popular political message for decades, especially since 2001, has been that to allow tragedy to fade from our immediate thoughts in the slightest is to dishonor and to disillusion ourselves. I think the most powerful, useful statement of this book is its rejection of the American preoccupation with remembering everything and being remembered and the belief that to do less is a failure of pride or moral will. If our Wikipedia entries disappear and our computers crash, so what? “We’ll be okay,” the same poem tells us. “We don’t need anything except what we will remember, and even that / will change, like a cloud whose rain is about to fall” (9).

That embrace of what cannot be known, like what we will remember or where we will end up, is a difficult path of faith, one that poetry and the poet can still, as Whitman maintained, encourage us in, although the practice is a solitary wandering. “Paul Klee’s Winter Journey at the Beginning of Spring,” my favorite poem of the collection, ends with an affectionate comment on the reader-poet/poem relationship:

Reader, I want to apologize

for bringing you here. I know you thought we were headed

someplace else. I confess I did as well. Grief is a

snow squall. It blinds but it too moves along. Do not be angry.

It might be cold, but I have left you the coat. (25)

Our wanderings, like our waste lands, are temporary, though painful and real. Throughout Landscape Portrait Figure Form, poet and poem offer us garments of warmth and kindness that help us endure the loss of control over the narrative of ourselves and our intentions. We cannot save everything nor have everything, but when we stop cherishing origins, ends, and the superlatives accompanying them, we enter a landscape of adequate comforts and plenty of company.

1. Walt Whitman, “Preface 1855, Leaves of Grass, First Edition,” in Leaves of Grass: A Norton Critical Edition, ed. Sculley Bradley and Harold W. Blodgett (New York: Norton, 1973), 711–31.

2. Walt Whitman, Democratic Vistas and Other Papers (Amsterdam: Fredonia Books, 2001); see especially 64–66.