'silence isn't always a trick'

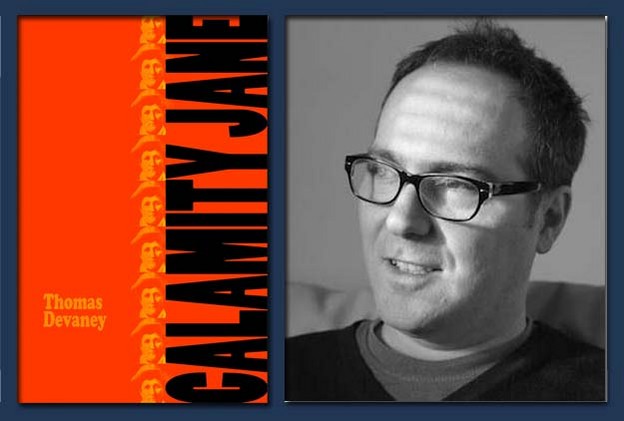

Thomas Devaney's 'Calamity Jane'

Calamity Jane

Calamity Jane

Thomas Devaney’s dedication for Calamity Jane, “A Solo Opera for Jeanine Oleson,” situates Calamity Jane — famous as a gunslinger, sidekick of Wild Bill Hickok, and heroine of dozens of dime novels[1] — more overtly in the realm of dramatic performance than in the realm of Western myth. Born Martha Jane Canary in 1856, orphaned at ten and left alone with two younger siblings, she became widely known as the character implied by her nickname, which she claimed to have earned while working as an army scout during campaigns against Native Americans (when she reportedly also began dressing like a man).[2] Calamity Jane fascinated the nineteenth-century public, just as she has the twentieth and twenty-firsts, who consumed her many biographies and sought her tales of swilling whiskey, swearing, and shooting. Staged as an opera, Jane’s largely apocryphal life story, the excesses of the Wild West, and the theatricality of American history, somehow become more obvious and — in the homeopathic philosophy of “like cures like” — quieter, less desperate, far stranger, and both too meager and too elaborate for the uniform contours of western narratives, of big and little “w” types.

In this reflectively performative space, Jane’s awareness of herself as a story that’s been told many times remains in the foreground to hold open (rather than to settle) questions about what’s real and what’s true. Calamity Jane begins and ends with poems that inspect givens of measurement, gender, and human and higher law, and extend that skepticism throughout the book to the illusory American vision of control and domination. The book’s opening poem, “Martha Canary,” asks,

How far though?

How far west?

How dry the air?

How frozen the ruts?

[…]

Who doesn’t believe her own eyes?[3]

These first lines establish the book’s questioning of limits, moral and territorial. The answers frequently come in words of non-being, negation, and indefiniteness: “nothing,” “no,” “nowhere,” “no one” fleck the poems Jane utters and predict the diminishment of empirical certainty Jane’s “real story” (3) effects. What she has seen and done often exceeds description and belief, as well as the narrative forms in which she is cast as part of the American epic. Ending in the line “only ever out,” “Martha Canary” predicts the receding frontiers of history, truth, nation, and self the book and its speaker-subject become. Delivering in song-poems her venture into the unknown — that stays unknown in the Western traditional sense — Calamity Jane profoundly upsets coherent views of American history and its storytelling.

This disturbance is accomplished by the personality Devaney develops through Jane, which, tellingly, does not speak loudly or more authoritatively than other versions of her “real story.” Although she does occasionally reference the inadequacy and irrelevance of storytelling to her experiences, Jane, who sometimes speaks to an unidentified interviewer and sometimes speaks about past interviews and the novel and newspaper stories they resulted in, talks and sings in a voice shaped by listening carefully. “Jane Improvises a Popular Tune in Her Head” demonstrates the blunt musicality of this voice and the humane patience harmonizing its grace and gravity:

Usually when I am talking to people

I don’t talk so much. They talk plenty

for both. The truth is, I like to listen;

whatever they want to say, it’s fine with me,

it really is. I don’t know how else to live,

but they can talk all night. The good and

the good try, I’ll listen. The winds

of a hundred winters never end. Yesterday

they were howling down from the mountains

right up my back — a shove and a chill;

those gray wolves and that dirty sagebrush smell again;

a child swept away. (13)

The acute attention to other people’s speech anchors all the work of this impossibly fine collection. Jane’s loving unselfconsciousness, conveyed by her affable assurances, “it really is. I don’t know how else to live,” indicates lack of interest in engaging with forms of authority essential to nationalism or markets, whether to combat them or to yield to them. While no one poem from this book can represent its emotional or formal range properly, the turn this poem takes illustrates the way Jane’s voice carries from familiar narrative generalization (“Usually when I am talking to people”) characteristic of prose and conversation and into poetry’s compassion and abstraction, “The good and / the good try, I’ll listen.” In this elegantly compressed movement from describing conversations with chatty strangers to private philosophy, Jane articulates a respect both for divine (like Plato’s Good) and for mortal intentions: God tries and good people try; those who try are good, and succeed or fail, they deserve, in Jane’s thinking, to be heard.

At the poem’s indented turning point, that compassion blows back into personal vulnerability emphasized by the brutal sensuality of the weather and landscape. In that furious howling of a hundred winters’ winds “right up my back,” the chronology muddles and collapses, along with the tactile, aural, visual, and olfactory imagery. A hundred years and yesterday, a woman’s back against the mountains and “a child swept away” swirl in the momentum of emotion and memory, both as unpredictable as the land and the natural forces constantly reshaping it. Jane’s tenderness towards good intentions and personal effort, whether God’s or humans’, comes from her understanding that trying doesn’t really matter when wind and wolves attack. Neither innocence nor conviction will stop the child’s — or anyone’s — swift erasure. Into comfortable national ideals predicated on the primacy of individuality, Calamity Jane introduces the engulfment of non-self that terrifies and harasses, sweeps identity away and splits consent from freedom in the codeless West.

In this poem and in others, Jane abandons claims to self-mastery and the swagger of outlaw heroism essential to the nostalgia and decadence driving narratives of the West, chief among them the closely related myths of will power and exceptional character that sustain belief in progress. While Jane disappears into a vortex of sound, smell, and loss along with the destroyed child by the close of “Jane Improvises,” she more directly refutes the scripts of American individualism in poems where she counters the assumptions of her interrogators. “Jane on how she got by as an Orphan” begins with the line, “The answer is, I didn’t,” and she later summarizes, “More than once I was left for nothing” and “There was nobody, just me.” The poem’s close underlines the urgency of basic needs (instead of restlessness for new challenges) directing her celebrated adventures, “I’d go anywhere where there was fresh water”; the phrase “anywhere where” — duplicating the anonymity of place and the depletion of the imagination — further stresses the desperation to escape cold, thirst, and terror overwhelming the body and eclipsing the mind. Such language that discredits humanist and especially Romantic ideas of individuality and the wilderness through which individuation most effectively emerges reverberates in poems like “Fort Russell,” which ends, “Nothing, nothing. / Blank and nothing — / how long was I nothing?” (22). Jane’s de-idealization of her adventures casts suspicion on the foundations and products of the American literary tradition from Hawkeye to Huck, disqualifying the “usable past” it promotes and invents.

This conceptual shift has formal implications as well. Throughout the book, the limits and definitions of Jane as she has been written and the American West for which she performed as metonymy on Wild Bill’s stage are revisited in the poems’ reversal of the dramatic monologue format. As in the book’s opening lines, what Jane doesn’t know and knows she doesn’t know — how far, how cold, how long, how gone she has been — recasts her life as a wonderment of struggles and luck unrelated to hard work or moral will, not a triumph of the pioneer spirit supporting Manifest Destiny. Not only do these strategies change the dramatic monologue’s lesson about a speaker’s arrogance and the dangers of talking too much, but they also indict the audience for its smugness. Devaney’s Jane is both wise and endearing in her understanding of cruelty (unless it’s directed at horses), but she does have rare moments of condemnation reserved not for the rapists and racists, but for interviewers and readers who mask their indecent curiosity as research or truth-seeking.

In “Fielding the Same Question in Other Words,” an annoyed Jane corrects the dime-novel notion that the West has some understood set of rules of conduct she continues to honor by evading the issue of her conjugal life:

What else can I say? I never was polite.

But I’d never ask something like that;

never ask anyone about bygones like that.

It’s not a code. The West isn’t a code.

I’d just never ask those type questions. (17)

While Jane bats away the fiction that the West was an inscrutable system navigable by those few initiated to and surviving its wilderness, the poem “Fort Laramie continued … ” confronts the complementary motives in which historical interest tries to cover for salaciousness. The poem begins, “I didn’t want to have to insist, but now I have to insist. // Stop with the fucking Laramie questions” and ends, after stanzas confirming a time of constant sexual violence, “What the fuck did you think I was going to say? // Fuck you for fucking asking” (24). Although Jane rebukes a specifically addressed “you,” she’s also calling out anyone who’s eagerly sought the gory details of another’s suffering — whether to provide self-congratulatory contrast to ethical codes and conditions of the contemporary world or to expose self-righteously the wrongs committed by “heroes” and “great woodsmen” against past innocents in the name of national expansion, discovery, or civilization. Fuck them for asking, and fuck us for wanting to know.

This foray into frank obscenity to renounce invasions of private misery, as well as many other far more discreet challenges to misguided assumptions about the Wild West, brings to mind (and not only because of the book’s connection to opera singers) Lauren Berlant’s notion of “Diva Citizenship.” Like Berlant’s real and fictional African-American divas who interfere in the presumed race and gender neutrality of American ideals, Jane’s speech accomplishes a “dramatic coup in the public sphere in which she does not have privilege” that “does not change the world” but seriously vexes the operations of “dominant history.”[4] In “Fort Laramie continued … ” Jane’s Diva Citizenship intervenes in narratives of male exceptionality — heroism, greatness — that often have dramatized and justified their exploitation of land and bodies, partly by locating brutal actions securely in the past. Positioned at a temporal remove, violence exacted and violence survived often become forgivably miniaturized beside their perceived results in the present (like we learned our lesson and won’t let it happen again). Jane’s bitter account of being “Fucked and fucked worse” by men and boys alike challenges the safety of chronological distance with the most basic materials of heteronormativity. The emotional immediacy of Jane’s reaction, importantly, troubles the gender oppositions built into the “fucking” she references. Her anger rises because the interest in what male celebrities she may have encountered as either prostitute or public concubine is promoted by a heteronormative binary in which she is the captive or complicit feminine component, confirmation of which would at once challenge (because she can’t be one of the guys if she fucked guys) or reiterate (because fucking guys confirms her status as woman) her token woman status in otherwise all-male accounts of the West. But Jane’s diva challenge to her inquisitor — what Berlant describes as “flashing up and startling the public”[5] — and to us readers, too, is that the binaries of that ethical framework do not apply to her story, nor to our story. In the encampment, no one had a say; everyone was fucked, clueless, and joyless, all victims and all fugitives. Jane’s Diva Citizenship, her queered dramatic monologue that protects the right to remain silent of the abjected past, insists on more compassion and more complexity of identification from both tellers and readers of the American story.

Jane’s attention to the gendered paradigms that have distorted her story leads to further complications of humanist logic that become especially vivid where she counters the preoccupation with pinning down her sex in order to stabilize her gender. “Blood-and-Thunder Stories,” which operates as one of several introductory poems, begins, “Was I a woman?” Here, and in the book’s closing poem, “The Dead and the Dead,” in which she says, “Someone said I was a man” (45), Jane wonders what has made people ask and speculates in both poems that answer and cause lie with her speech, not her anatomy, conduct, or appearance. In “Blood-and-Thunder,” Jane confirms her womanhood by stating, “Strange that my cursing would show it most” — that “Cursing is a marker between me and men; / and one between men and animals.” (2). When rumors that she is really a man persist, Jane looks again to speech, in this case what she hasn’t said, as the cause for this: “Why? Because I know something I won’t tell? / […] Because I never say I ain’t? / Don’t know” (45). That final statement, “Don’t know,” ends the book in astonishment at what worries and interests people, but it’s a directive, too — don’t know and don’t think you know what people have done or who they are. Listen instead.

Jane’s abdication of moral absolutes in favor of listening gives Calamity Jane its deeply ethical orientation and makes her Diva Citizenship especially compelling. Her insights “flash,” “startle,” and “estrange” familiar explanatory structures of the American past and its authorization of the present, but far more often, Jane models sympathetic humility for the many, nameless transients who, like her, have been at the mercy of luck and weather. Throughout, Jane charts the unpredictable ways power, her own and others’, slips and slides out of conventional modes, like comedy or tragedy, success or failure. She recognizes the false ideological goods her story has helped to sell, yet is glad to “dine out on Wild Bill ’til the day I die, / and in the hereafter too” (17). She accepts gratefully the celebrity name that provides “the best place … to hide” (14) and that makes her story true, despite her real story never having been told.

Even a poem like “All Men Are Mean” twists a generalization into a reminder that perspective and context make exceptions always the rule:

—mean doesn’t mean all bad.

Some bastards are just that: hardened.

Listen, silence isn’t always a trick.

Nice folks aren’t always so nice.

At least with a mean guy you know where you stand. (18)

Collective terms like “mean men” or “nice folks” don’t mean much, and self-knowledge beyond one’s basic skills, like caring for the sick or shooting straight, is a foolish, false consciousness. “No one knows what it’s like to be a man — ” she says in “Something about Men,” “not even the men” (28). Jane often seems a genuine innocent in her steady refutation of interior and exterior selves needed to underwrite epiphanic transcendence (the spiritual version of economic and historical progress), but she is wily enough to recognize when mere words fail. Then, only song can carry the intimacy and horror of the West, a song emerging from silence — not the kind that tricks another into talking more than he should or lies by omission, but the silence required of listening, and of empathy allowed by the courageously unprotected state that invites it.

“Jane’s Daughter,” perhaps the book’s most affecting poem, equates song with the coextensiveness of mother and newborn, a point of pure contact that becomes the invisible, powerful center of a community:

I wanted to tell her something.

Nothing,

there was nothing else.

We were there: she with me,

and me with ye, I’d say.

She holding me, me singing —

the bare wet of it.

There’s no night to take away.

A fit of tears with nowhere else to go. (40)

Called by the song, men and women of many races and nationalities leave the small family humble but badly needed gifts: among them, a moss bag, clean towels, food, and a washing bowl. Through this maternal template, song becomes a vortex, a still point around which gathers a world of listening fields and people, who may hear the song “but never get a look.” This gorgeous, peculiar moment near the close of Calamity Jane seems nearest to divining an antidote for the arrogant ills revealed, unraveled, and forgiven through its restaging of the Wild West. Removed from spectacle and performance, yet singing and meeting “in thirst” for love, kindness, and nourishment, the “nothing” Jane wants to tell her baby becomes the beginning of another possible narrative, one in which people who have nothing offer all they can, in a very different national opera of gesture and generosity.

1. The Deadwood Dick novels, the “most popular dime series of all time” by Edward Wheeler, secured and promoted Jane’s celebrity, although the stories rarely resembled her actual actions or personality. See Richard W. Etulain, “Calamity Jane: A Life and Legends,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History (Summer 2014): 27–28. In 1896, she travelled briefly with the Middleton and Kohl dime museum show, which billed her as “Famous Woman Scout of the Wild West” and “Comrade of Buffalo Bill and Wild Bill,” hype that led to a century of misperception that Jane worked for Bill Cody, a story Buffalo Bill himself capitalized on after her death, although Jane never did join his show. See James D. McLaird, “Calamity Jane: Life and Legend,” South Dakota History 28, no. 1–2 (1998): 14–15, as well as James. D. McLaird, “Calamity Jane and Wild Bill: Myth and Reality,” Journal of the West 37, no. 2 (1998): 31.

2. Jane’s birthdate has often been thought to be 1853. Her tombstone incorrectly stated her date of birth as 1850, but she was forty-seven at her death in 1903. See Richard W. Etulian, “A Life and Legends,” 33.

3. Thomas Devaney, Calamity Jane (Baltimore: Furniture Press Books, 2014), 1.

4. Lauren Berlant, “The Queen of American Goes to Washington City: Notes on Diva Citizenship,” in The Queen of America Goes to Washington City: Essays on Sex and Citizenship (Durham: Duke University Press, 1997), 223.