The poet's novel

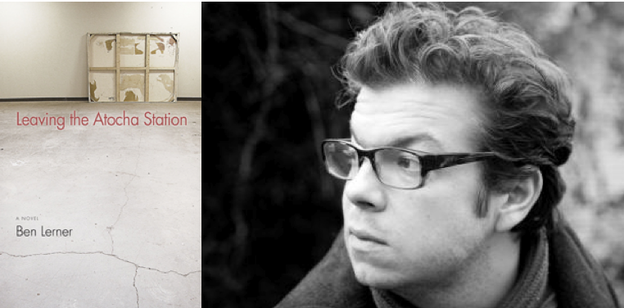

A review of 'Leaving the Atocha Station'

Leaving the Atocha Station

Leaving the Atocha Station

Some poets transition from poetry to novels rather in the spirit of an enlisted man joining the officer corps. Denis Johnson comes to mind as someone who turned from poems to novels without looking back; even more prominent is the case of Michael Ondaatje, whose best fiction, I think, still has a foot in poetry (Coming Through Slaughter, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid). Others, like Stuart Dybek and Charlie Smith, may continue to write poetry but nevertheless have passed on, have risen or fallen to the identity of the fiction writer.

The rarer and more interesting cases, to my mind, are those poets who write fiction but remain poets. Joyelle McSweeney has written two novels, Flet and Nylund, the Sarcographer; but because their prose is often strange, calling the sort of attention to itself that prose fiction rarely does, they don’t sacrifice the eccentricity of poetry. Better known is the case of Roberto Bolaño, who began as a poet but became famous as a fiction writer. As far as I can tell from the one volume of his poetry that I’ve read, the world is entirely justified in esteeming him only for his fiction; yet he thought of himself as a (failed) poet and I persist in thinking of him that way, for the strange anti-eloquence of his writing and his hilarious grim persistence in writing always only about poets and their rancid idealism.

Flet by Joyelle McSweeney (Fence); Tree of Smoke by Denis Johnson (FSG); Coming Through Slaughter by Michael Ondaatje (Vintage)

I suppose that’s really what I’m talking about here: those poets who write fiction as a bid to enter the center of literary attention that novels nominally occupy, versus those who, through temperament or incompetence, are destined to remain ex-centric.

Then there’s Ben Lerner. A ferociously ambitious and successful younger poet from Topeka, Kansas, Lerner, a one-time recipient of Fulbright fellowship to Spain and the author of three generally acclaimed books of poetry, has just produced his first novel, Leaving the Atocha Station. It’s about a ferociously ambitious and successful younger poet from Topeka, Kansas, albeit one who is not yet comfortable with or fully conscious of either his ambition or his success, on a Fulbright-like fellowship to Spain. His Adam Gordon is as transparently autobiographical as is Bolaño’s Arturo Belano, and at the same time both alter egos are presented to the reader through veils of irony and self-loathing.

In his first-person narration, Gordon presents himself to the reader as an almost entirely dysfunctional human being, preserving a semblance of autonomy through the use of various drugs, prescribed and otherwise. It is not at all clear whether we are supposed to respect his poetry or not — a few samples are presented that do nothing to defy Tony Hoagland’s persistent denunciatory motto, “the skittery poem of our moment.” Gordon himself doesn’t respect it but Teresa, a Spanish translator and one of two attractive women that he finds himself entangled with, respects it enough to want to translate it and publish it in a handsome chapbook edition, a reading from which at a gallery in Madrid is the culminating event of the novel.

Lerner even goes so far as to give Gordon his own nonfiction thoughts; as a note on the copyright page tells us, “The novel includes, albeit in altered form, a reading of John Ashbery’s poetry that first appeared in my essay, ‘The Future Continuous: Ashbery’s Lyric Mediacy,’ published by boundary 2.” He also does not fail to remind us that “Leaving the Atocha Station” is an Ashbery poem (one of his most obscure, which is saying something); Ashbery, and the world of poetry Ashbery has bequeathed to us, haunts the book. For much of the novel Gordon is preoccupied by his lack of fluency in Spanish and his attempts to use that lack of fluency “to preserve the possibility of misspeaking or being misunderstood, and to secure and amplify the mystery” that comes with language that fails to be fully communicative.

Poetry books by Ben Lerner: Angle of Yaw (2006), The Lichtenberg Figures (2004), and Mean Free Path (2010)

The consonance of this with poetry, in its deliberate obscurity, its refusal to be “about” anything, is entirely deliberate and forms the major theme of the book: the failure to be present to oneself or to others, in one’s own life or in History writ large (the most significant event in the book is the 3/11 Madrid train bombings, the aftermath of which Gordon witnesses). Language, or rather language’s failure, finds the pathos in this travesty of alienation, even as Lerner finds comedy in it; as Gordon reflects at a poetry reading he gives, “I told myself that no matter what I did, no matter what any poet did, the poems would constitute screens on which readers could project their own desperate belief in the possibility of poetic experience, whatever that might be, or afford them the opportunity to mourn its impossibility.”

Gordon/Lerner may intend this as cynicism, but like any display of cynicism there’s a bruised idealism at its center. “If I was a poet,” he thinks later, “I had become one because poetry, more intensely than any other practice, could not evade its anachronism and marginality and so constituted a kind of acknowledgment of my own preposterousness, admitting my bad faith in good faith, so to speak.” If one is a bad poet, a false poet, that does not injure Poetry’s eidolon; much harder and more adult is to accept that poetry, like any art, can fail as often as it succeeds, and as a human being one can be part of that success or failure and bears the responsibility for trying.

So we have here again another portrait of the artist as a young man, which like Joyce’s novel displays a good deal of irony toward its protagonist without completely disowning either his idealism or the writer’s own ambitions, albeit in a negative, almost Gnostic form.

I can’t decide yet whether this novel constitutes a bid for centrality — if Lerner will now be leaving the Atocha Station of poetry for the maculate shores of fiction — or if its obsessive focus on poetry and failure will consign it to eccentric status. It’s quite funny, I should say — in his self-inflicted humiliations the protagonist reminds me of nothing so much as an intellectual Larry David — and there’s some interesting if lightly milled grist for considering Gordon as an archetypal self-involved radical artist from “the United States of Bush.” How archaic already that designation seems, another sign of American innocence as inexhaustible destructive resource; as Gordon remarks in one of his endless attempts to sound deep without actually committing himself, “The proper names of leaders are distractions from concrete economic models.” The fatuousness of this, even in its truth, damns the helpless self-regard of the beautiful-souled American Left with withering effectiveness.

In an interview with his friend Cyrus Console (who also turns up as a character in the book), Lerner speaks of Adam’s predicament in terms of aesthetic position: “the virtual possibilities of art are always in a sense betrayed by actual artworks.” What fascinates me is how the positions virtual and actual (terms, Lerner tells us, taken from Allen Grossman) roughly correspond to the two genres under consideration here. Poetry, at least modern poetry, in its fragmentation, its gesturality, is the quintessential art of the virtual: it suggests, Gnostically, the withdrawal of the numinous from the space of the poem. The novel is a creature of the actual, even in its greater physicality as object (a distinction rapidly eroding); as young man, I thought to write a novel, like reading one, was in some way to participate the real. (Fantasy novels, oddly, for me always bridged the gap: their worlds were not real but painstakingly actualized, even as their endlessness, their tendency to trilogize or series-ize, dovetailed back into the virtuality of the always-incomplete. This is why I halfway hope that George R. R. Martin doesn’t finish A Song of Ice and Fire, to preserve some speck of the virtuality the TV series had devoted itself to shredding. End of digression.)

“I promised myself, I would never write a novel,” Lerner’s protagonist says — or is his promise really a dare? Poetry perpetuates adolescence through its refusal to actualize: a poem in itself is like a young man dawdling his way through college, refusing to declare a major or propose to his girlfriend, refusing to commit, to engagé. This is the pathos of poetry, even to the point of “Pathetic!” But it’s also the source of poetry’s great reserve of utopianism and hopefulness, even when, tonally, it despairs. Oh I’m sure there’s a poetry of the actual as well, akin to what Robert Van Hallberg calls “civic” poetry so as to distinguish it from the Orphic. But if the former is more grown-up, more resigned, it lacks I think the power to shake the heart that comes with the Orphic. The tragicomic valley of hesitation between them is where Lerner’s novel is located.