Poetry as path, as weapon

On Uche Nduka

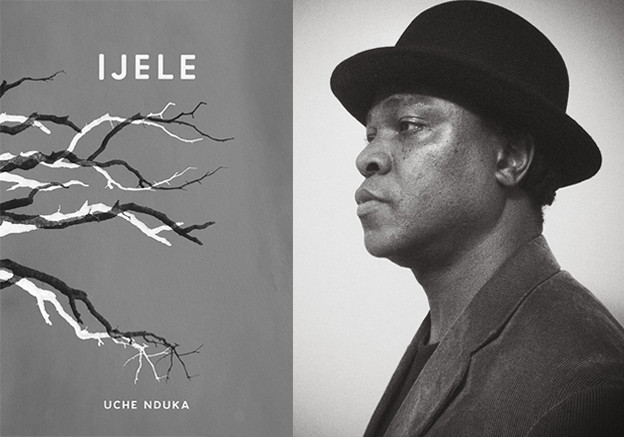

Ijele

Ijele

How many poetries are there; how many could there be? The poetry of investigation, the poetry of protest, personal poetry, national poetry, international poetry, documentary poetry, poetry of war and peace, emotional, environmental, philosophical, identity poetry. And what’s at the root of all these poetries, if anything? Poetry as a way of approaching the world — as the urgent effort — probably futile — to get at something inside or outside through language — or to escape into language as a way to survive a brutal material or psychological world. Somehow language — the effort in the ineffability of words — can save us if we can engage at a deep enough level to get past the pain. That’s then a poem and more than a poem. It’s a mode of living. What we call a poem might not be more than a momentary snapshot of an ongoing life in language — a dislocation, an exile.

Some thoughts on reading Ijele, a powerful prose text by the Nigerian poet Uche Nduka. Born in 1963 into a family of Christian priests, Nduka was brought up bilingual in English and Igbo and earned a BA in English from the University of Nigeria in 1985. When he was four years old the Biafran War (the Nigerian civil war) broke out. Possibly as many as three million people died in that conflict, many of them children — Nduka’s generational peers — mostly from starvation. Chaos and ethnic violence in Nigeria preceded that war and continue to the present. Top Nigerian government officials regularly and spectacularly fleece the nation’s coffers. The bloody terrorist activities of Boko-Haran, whose members recently broke into a boarding school and slashed the throats of students asleep in bed, go on without restraint.

Nduka left Nigeria in 1994 for Germany, when he won an arts fellowship from the Goethe Institute. He’s lived out of the country ever since, in Germany and Holland for twelve years, and in 2007 emigrated to the US, where his parents and family live.

Given this background, it’s clear that for Nduka, poetry has had to be much more than a polite profession or an aesthetic preoccupation. He has of necessity had to find in poetry a means of survival and a method for fighting back. No way to set aside the scars, the disappointment, and the social rage, and go on to write a poetry of reflective personal feeling. Also, it would seem, no way straightforwardly to attempt to describe or depict the immensity of what has been experienced and felt — writing would have to take you beyond that to a more total or global sense of engagement with language as defiance, as hope, hope not for a probably impossible political solution to the chaos, but hope for a present, in writing, in which sanity and endurance prevail, even as the pain is confronted head-on. At any rate, this seems to be what Nduka’s writing does. Poetry as path or weapon — as life.

i had barely been born when i nearly lost my life. that music is not higher than the unity of pines. how intact am i. how intact am i. how intact are you. i should turn my back on them:these opened wounds may swallow me. we make claims for the land hoping it will not betray us.quandrants of parenthesis.overnight, waterlilies rose and sent mails to him.waterlilies speaking for the lodgers. not a few are anatomically incorrect. (“Overnight,” 25; unconventional spacing in original)

A prize-winning poet well connected in Nigerian and African literary communities, Nduka writes in the Western avant-garde tradition, but without particular affinities that I can see, judging at least from the work in Ijele. What’s inspiring about the book is its line by line intensity, and the way it simply states, baldly and without pathos — almost, at times, coldly, without regret or protest — its themes of sexuality, dismay, exile, resistance, dislocation, without any promise or redemption other than in the text itself. The book consists of eighty one-page prose poems (a few are longer) written in mostly disjunct sentences without capitalization. The compositional method seems to be improvisational, listening on a word-by-word basis for what seems to want to come next, and allowing that to happen, celebrating surprise, spontaneity, contradiction, reaching out for something not yet realized. Onward, always onward. Yet the poems do not wander or drift — there’s a driving rhythm and insistence to them, an urgency, a sense of defiance. I found the text frankly difficult to read for its density and intensity — I kept wanting to read on, but sometimes found that difficult to do; I needed breaks. So it took a while to get through. Ijele seems intent on doing its work, reader or no. Nduka is a fiercely independent writer.

So far I just like doing my own thing and not buying into the hype of either formal or informal English; traditional or avant-garde usages. I enact a language style that suits my mood and the subjects I am interested in. Linguistically it seems there are a lot of trenches that have not been explored in poems/poetry. I keep attempting to investigate them. I don’t want to feel like people expect me to write in English timidly. I have always been wary about the conformist pressure of Nigerian, African, European, and American literary scenes. Yet I guess I am not fully in possession of the knowledge of the things/factors/situations that motivate the shifts in the usage of English in my work. I try not to overthink this phenomena. Pushing the boundaries is what a real poet does. I am writing about the United States of America now, but with my eyes wide open. (Nduka to Johannes in Montevidayo, September 24, 2103)

Wanting some information on the word, I ran Ijele through Google translator. In Zulu it means “prison” or “warder.” In Igbo it’s the title for a traditional masquerade about a courier between the spiritual and physical worlds — in the case of Nduka’s poems, between Nigeria and Europe/America or between the social horror and triviality of the world and the possibilities for survival with integrity that a life of poetry provides.

words invite us to take part in stamping their feet; in thrashing the desks of belles-lettres;in scorning the mirage of a bookworm; in fusing bindweed and algae. my logic cannot catch all the spoils of the possible. my past momentarily cannot cease being a thirst. being no visitation of a whip, being no visitation of loss, the subterfuge of a needler is patently absurd. this present incarnation of the philosopher’s stone does not interest me. some courtesies are diabolical. overall the fowl has bled to its limit. interruption is our condition. in interruption is our trace. the way in is not the way out. going in the direction of thirdness it is better to be incensed than bored. (“Branching,” 72)

As a writer concerned with poetry as more than poetry — poetry as a life in language that can realistically confront the world as it is without going mad or resorting to the various impressive strategies for distraction that our present world has on offer — I am drawn to Nduka’s work. Because of what he has seen, what has formed him, there’s a level of passion in his work beyond what’s normal in much other writing today.