'The lip of a paragraph'

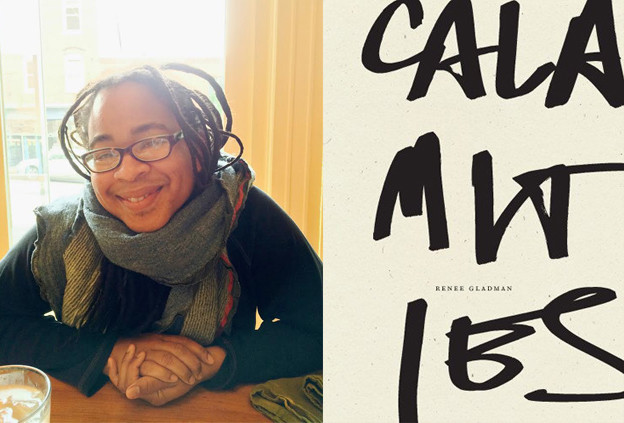

On Renee Gladman's 'Calamities'

Calamities

Calamities

On the last page of Renee Gladman’s Calamities is a thick line drawn upon its lower portion. Beginning from the leftmost part of the page, it extends out to the right where it is cut off by the righthand side of the page. The line is one of Gladman’s principal preoccupations; its depiction here, as one abruptly stopped by the edge of the page, seems to me to epitomize the unrepresentability of a line. A line is infinite (a line drawn between point A and point B is, geometrically, a line segment), and so the line on this last page, marred by a threshold, is, perhaps, the only way to characterize its infinity, its perpetual, outward reach. Guillotined in this manner, the line demands conceptualization but collapses at the edge of actuality. Although the line is cut off, it doesn’t necessarily seem to or feel like it’s going to stop. There is a certain decisiveness, an aggression, that this line contains. Yet, despite its longing for an ineluctable propulsion, the cut-off line exemplifies the vexing frustration of trying to represent something that seems fundamentally unrepresentable. And this irritating impasse is redoubled in Gladman’s attempts at writing narrative and making a writing narrative. Calamities, in other words, is an exercise in performing the difficulties of writing the space of writing itself. I employ “writing” in its verbal and gerundial sense: on the one hand, the act of writing narrative, and on the other, the case for Gladman’s work as a writing narrative — a congealing plasticity wherein, with its questions, propositions, tangents, walls, obstinacies, disentanglements, and conglomerations of thought, writing jettisons itself away and toward its zero degree. [1]

Calamities is a practice in attempting to represent, through vestigial accounts, or “small acts,”[2] the “thing” of narrative itself. I use this rather dumb and elusive term as I hesitate to designate it as anything other than a concept that requires thought and then its immediate relinquishment so as not to fossilize its distinctiveness. Not a core or kernel of narrative but “thing” as a placeholder for the space between thought and inscription. Therefore, in addition to the question of the line’s infinity and its impossible representation is the question of the line as inscription: “The line came out of the hum most of the time and it landed in the space of the page, becoming buildings, becoming paragraphs, being a suggestion of urban planning, being a suggestion of energy, how energy behaves in space” (114–15). The line is a projectile, a unit of meaning, which finds its expediency on the page. Later in the work Gladman will explore the consequences of the line as regards drawing and writing but not, let us make the distinction, drawing versus writing.

The body is employed whether one makes marks on the page or types on a keyboard; “thus, drawing is writing” (104). Gladman reminds us that any kind of inscription is, fundamentally, about making lines, even if these lines emerge before us on a monitor. The equivalency that Gladman makes between drawing and writing is most readily grasped in her admonition that “a drawing was also a paragraph of writing” (117); therefore, a line is “drawing writing” but also just writing (110). The reminder elicited by the fact of drawing/writing as a material and visual construct, and one that necessitates language and interpretation, means that Gladman’s investments congeal around “the questions that led to writing” (5). In other words, Gladman is interested in the space of narrative, which either transpires in drawing or writing. This is expressed in Gladman’s own perplexing ruminations:

I kept writing that I was no longer writing, but then also looking at the drawings: shouldn’t they be better if they were now all I had? I had to write in order to figure out what I wanted from the drawings. And I had to write in the drawings as if drawing because this helped me formulate what I wanted to ask: At what point? At what point did my sentences become this way? (120)

It is, therefore, not so much that the equivalency between drawing and writing impoverishes meaning; rather, it relocates narrative thought within an interstice: “you coveted that ability to think in paragraphs with a single sentence” (43). If the thought of paragraphs can be expressed as a line or a single sentence, then what Gladman is interested in is that generative space where that thought takes place, and not solely its mode of expression. This interior space is described as trying to write “about narrative inside of narrative” (6).

Calamities contains brief poetic essays that meditate on writing, reading, speaking, drawing, transcription, administration, lovers, baths, race, sexuality, geometry, and motion. Up until the section called “The Eleven Calamities” (there are, in fact, fourteen), each essay starts with “I began the day.” Gladman returns to this inciting proclamation in the fourteenth calamity, the final essay of the book. Despite the authoritative force, certainty, and apparent description of the beginnings of narrative in each essay, the irony of Gladman’s acts of narration is that one constantly feels stuck in some narrative rut.

Gladman generates a type of description that’s neither metafictional nor strictly autobiographical. I do not want to attribute this writing to the interior space of a writer’s mind (although such an interiority is sometimes furnished to us readers). Gladman admits this herself: “not those asinine problems of writer’s block or other equally frustrating problems of self-worth (feeling too much or not enough)” (5). Gladman therefore situates herself in the space of the “writing subject.” The writing subject may index the writer as a subject who is writing, as well as the subject of the writer. An easy way to make this distinction would be the narrator versus narrative. But it is precisely the dissolution and eventual discarding of such boundaries that ultimately interest Gladman.

I do not want to proposition an either/or of writing. Rather, Gladman, attempts to access the space of the writing subject (the being that is narrating and what is being narrated) as a way to explode the very terms that distinguish them in the first place, with residual consequences on such distinctions between form and content, subject versus object, inside versus outside. The sentence/line therefore offers the opportunity for modality, maneuvering, and improvisation as it depletes the space between thought and enunciation:

One of my favorite words was in my mouth, and I was torn between chewing and swallowing it, so that it could become a part of me, another organ that processed or eliminated some material of my being, or spitting it out immediately, without doing any damage to its form, so that I could study the word in all its glory. That word was sentence […] I was ready for its philosophy; but when something is in the mouth, there is not always that clear relationship of container to contained. (95–96)

This is precisely why the fold serves as an apt metaphor for the experience of reading Gladman’s book. If you take a piece of paper and continually fold it into halves, the number of folds increases while the size of the piece of paper decreases. The fold is at once additive as it is subtractive. Folds, as they increase in number, generate more and more possibilities, and completely reimagine the space within which they are reconfigured. Space is reconfigured, (re)constructed, diminished, and translated along new and different planes. Folds help us break down the “inner” and “outer” of our experiences of the world (“Could I talk about narrative as I was operating within it?” [7]). But the positing of the internal and the external, closed and open quotes, does not function to hypostatize the difference, but to add to its extremities. In Gladman’s text, we learn to trace how these distinctions become less and less significant; writing inside narrative is merely one of many conceptual folds that, in its immediate assumption, is displaced to another point of reference. Each essay feels knotted; like being in a mouth. And one is never quite sure about the space of enunciation. The fold of narrative is not singular; it stacks itself against other narrative folds only to illuminate constellations of thought. But what becomes necessary is not the untangling of its density but the tracing out of its textures, surfaces, and shapes. A fold is something binding yet elusive; its status is only determined by the meeting of two planes which may obscure the fold itself. It is therefore not in the name of teleology but of experience that we must seek a phenomenology, an erotics, a contouring of writing.

Let us return to the philosophy of the sentence. It is precisely in thinking about the sentence as a line, as something that promises teleology but can only deliver on an unfathomable infinity, that we may emerge at the point where narrative does nothing. The preoccupation of the philosophy of the sentence is demonstrated by one of Gladman’s slips of the tongue, where “the city” is the “errant word” for “the sentence” (3). This unconscious error reveals a lot about the relationship between the sentence and the city. Errancy is apt; in addition to the mistake of enunciation, it actually does more to link the sentence with the city as it brings about, and aligns the sentence with, notions of psychogeography, the flâneur/flâneuse, wandering, trajectories, routes, crowds, and inner/outer experience. Gladman’s attention to the urban, the geometric, and the architectural is bountiful: “buildings first, then people” (52); “something that was geometric, but also a poem” (60); grids, matrixes, sieves, and their holes (34–35); “picture-feeling” (43); “land-shape” (108) — in short, writing as “geometry instead of verbal consequence” (44). Metaphors of the visual and the constructed help to reiterate Gladman’s conceptualization of drawing-writing.

This is not, however, strictly about the nature of form and content (although those are of interest) but of some space within which the question of writing is elicited. What are the questions, the inclinations, and the emanations that lead to narrative (in whatever form they take)? While it can often feel that this narrative space of production attempts to register the affective space wherein “poetry comes from nothing” (35), that isn’t to say that it doesn’t touch upon aspects of other worlds. “Drawing,” as well as drawing upon, the objective world, in Gladman’s narration of acts of narrative, often involves pulling in and magnetizing things, objects, peoples, thoughts, and feelings that allow a world to be created.

For one thing, it isn’t difficult to see how a seemingly limited attempt at the description of narration can also resonate with the character of a sexual and gendered metaphor. It’s possible to see, for example, that the notion of the fold is one that can be aligned with anality.[3] There are a number of tacitly and not-so-tacitly suggestive terms and images that center the question of narrative around crevices, cavities, interiors, and gaps: the fold, the line, the dash (3), “Narrative—” (6), “writing about narrative inside of narrative” (6), “clos[ing] the quotes when I bottomed out” (8), “emanations” (34), the holes of grids and sieves, as well as the space of “nothing” where poetry emerges (35), “the lip of a paragraph” (55), the description of fabric draping over an ass as “penis-pocket,” “slit,” “pouch” (87), and writing about “trying to look at [the world], but it was lying on my face” (91). These terms and images can be collated into a catalogue of metonymic iterations of the (anal) fissure of narrative.

Talking about narrative therefore gets us to other fictional elements: story, plot, metaphor, patterning, events, affects. The difficulty with such a project, however, is summarized in Gladman’s desire to “say it was language with its skin peeled back but you couldn’t use peeled-back language to tell an audience that the drawings were language peeled back” (102). Undoubtedly, the peel brings us back to the beginning of one of Gladman’s essays: “I began the day inside the world trying to look at it, but it was lying on my face, making it hard to see. The word was made up of layers, one encompassing the other, and it smelled like onion” (91). I cannot help but be reminded of Roland Barthes’s “alimentary metaphor” of the onion as regards narrative.[4] As Gladman writes:

nor could I deny that seeing myself inside an onion or belonging to an onion (perhaps not quite located within it, locatable) provided a useful way to observe how I was a part of something that formed a sphere of folds, where one fold lay organically next to another, each one thicker as you moved outward, away from the core, though onions have no true core, or rather, no core that survives our trying to reach it. And that was why I thought it was difficult to understand this world. You dislodged the thing you were trying to find, and whenever you moved, it moved. (91)

Calamities, therefore, demonstrates an analogous claim toward the essay as what Gail Scott, in Spaces Like Stairs, describes as “a perpetual work-in-process.”[5] Part of the feeling of perpetuity is, in large part, due to this difficulty of trying to explain the thing you want to explain that is “language peeled back,” which moves as soon as you get close to scrutinizing it, dwelling in it, touching it, noticing it.

This might explain how the “calamities” are differentiated from the other essays of the book; Gladman writes that even though they “had become something quite different from earlier parts of the book,” they “belonged in the book all the same, and more so each time I tried to get out of the book” (119). The “calamities” make sense insofar as they represent Gladman’s inability to stop. More than a mere anomaly, the extra calamities not only index the possibility of the perpetuity of the work but, like the guillotined line, represent the excess of trying to articulate the very traces and folds of writing that seem to remain within our reach but constantly elude our grasp.

If there is any frustration in reading Gladman’s essays it is that the promises of their propulsive force are almost always left unfulfilled. And the book goes on to articulate this frustration to itself: “You had to be okay that it took you twenty minutes to make this multilevel statement and accept that you hadn’t actually scraped the surface yet of what you were really trying to see in this language” (43). What speaks, then, is the frustration of process itself — the representation of a genre of incompleteness. But what sticks is that it is the very sign of inventiveness that invigorates and animates reading and writing.

Reading Calamities is incantational. The reading experience is one drenched in the constant feeling of ignition and obstruction. Calamities at once demands and inhibits; it solicits and perturbs. It frustrates and tickles. And it reminds us, most forcefully, that narrative is erotically phenomenological.

I began this essay talking about the line on the last page of Calamities and the question of its infinity. It is true, however, that this line does have a point of departure. Theoretically, a line expands infinitely both ways. I wanted to begin this piece with the infinite character of the line as a way of thinking about Gladman’s descriptions of the difficulties of representation because that is what I saw in the line’s arrest. But how might we account for the fact that this line doesn’t extend infinitely both ways? Perhaps, another way we can read this last page is in the spirit of each essay: a line that says “I began the day,” and one that also challenges the infinity of the line by showing us its emergence from nothing, by showing us, likewise, how “poetry comes out of nothing” (35).

1. Roland Barthes, Writing Degree Zero, trans. Annette Lavers and Colin Smith (New York: Hill and Wang, 2012), 14: “A language and style are blind forces; a mode of writing is an act of historical solidarity. A language and a style are objects; a mode of writing is a function: it is the relationship between creation and society, the literary language transformed by its social finality, form considered as a human intention and thus linked to the great crises of History.”

2. Renee Gladman, Calamities (New York: Wave Books, 2016), 1.

3. Chance had me reading Eve Sedgwick’s essay on Henry James and fisting around the time of the composition of this piece and I owe her and her thought a great deal since it allowed me to think along similar lines about narrative fissures, cracks, surfaces, textures, and folds as they resonate and appear in Gladman’s work. See Sedgwick, “Shame, Theatricality, and Queer Performativity: Henry James’s The Art of the Novel” in Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003), 35–66.

4. Barthes, “Style and its Image” in The Rustle of Language, trans. Richard Howard (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1989), 99: “The problem of style can only be treated in relation to what I shall call the layered quality of discourse; and, to continue the alimentary metaphor, I shall sum up these few remarks by saying that, if hitherto we have seen the text as a fruit with its pit (an apricot, for instance), the flesh being the form and the pit the content, it would be better to see it as an onion, a superimposed construction of skins (of layers, of levels, of systems) whose volume contains, finally, no heart, no core, no secret, no irreducible principle, nothing but the very infinity of its envelopes — which envelop nothing other than the totality of its surfaces.”

5. Gail Scott, Spaces Like Stairs (Toronto: The Women’s Press, 1989), 9.