Renee Gladman and the New Narrative

Event Factory

Event Factory

The Ravickians

The Ravickians

Little discourse exists today, at either pole of high literary theory or pop discourse, that narrativizes the bond between the individual writer and the reader in poetry or fiction, other than metaphors of the “literary market” as a collective purchasing power or critical arbiter of taste. The death of the author coincided with the birth (and, some would argue, tyranny, in reader-response criticism, blog, and spectator culture) of the reader as a determinant of value and meaning.This is modernity’s grand narrative of failed representation (of war, and the “nothing that is not there, / and the nothing that is”: the horror vacui of the man, or a generation of men and women, without qualities), in what Marshall McLuhan declared to be our postliterate culture, wherein the author has been lowered from the status of sacerdotal epistemological subject (one who knows, and who disseminates knowledge), to a bureaucratic mouthpiece carrying out her author-function, to a ghostwriter of forms (canonical, extracanonical, or undecided).

The most well-known interpolation of a reader in nineteenth-century literature is “Reader, I married him,” from Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Roland Barthes’s The Lover’s Discourse (1978) and The Pleasure of the Text (1973), Toril Moi’s Sexual/Textual Politics (1988), and other essays by Julia Kristeva, Hélène Cixous, and Luce Irigaray constitute a few cornerstones in the textual hermeneutics, instantiated by Roland Barthes, of both écriture (writing about writing) and écriture feminine (the inscription of the female body and female difference in language and text), as well as theories of the lyric, narrative, personhood, and body politics. Choosing between the assembly and gleeful dismemberment of a purely citational, web-derived textual “body” (Flarf) or a version of Homeric mimesis (e.g., Kenneth Goldsmith’s Day, wherein he transcribes mass media’s ideology rather than poetic tradition) takes the questions of agency, intentionality, and framing (for writer or reader) and turns them into questions of proprietorship (intellectual property and copyright or droit moral): a swift divagation from the epistemological and ontological questions that haunted the modernists, from Sartre’s “What Is Literature?” to the question of whether a “poem” is defined or judged by its constitutive elements (its material body as expressed in syntax and line, meter and rhythm), its function (how it “works”), or its telos (was it “intended,” and if so, for whom). Writing to one’s audience is a doubled-edged sword. While pandering to the masses can be a means of survival at the cost of authenticity, limiting one’s projected readership to those schooled in academic jargon or in the parlance of an elitist (pop or hipster) coterie can also be forms of false consciousness.

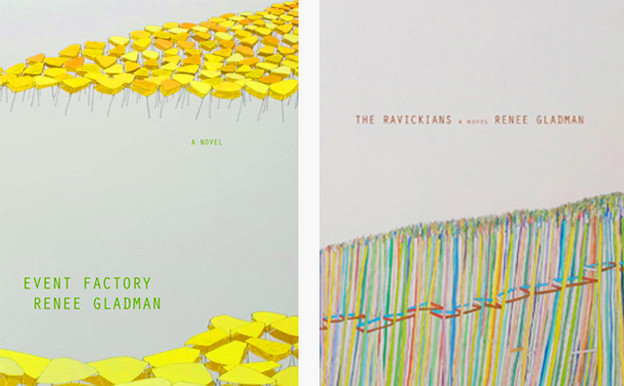

New Narrative writers mark the gulf between readerly intimacy and direct interpolation in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries and today’s habitus of authorial onanism as a symptom of capitalist alienation, and also as its source. One New Narrative writer is Renee Gladman, a professor at Brown University (school of experimental aesthetics). The author of A Picture-Feeling (2005) and several works of fiction, including Event Factory (2010), The Activist (2003), Juice (2000), and Arlem (1994), Gladman tests the potential of the sentence with the cartographic precision and curiosity endemic to the New Narrativists, whose work is framed in spatial rather than stylistic terms. Gladman’s work, and the work of other New Narrativists (Kathy Acker, Camille Roy, Michelle Tea, Eileen Myles, Laurie Weeks), borrows more from new performance theories than from narrative theories (Walter Benjamin, Louis Althusser), most of which insist on separating art from aesthetics, or operating within a performative frame rather than conflating form with content. A productive, Brechtian sense of the alienation effect is different from the totalized spectacle: the formal and real subsumption of aesthetics under capitalism and performance, anesthetizing emotion and the participatory real. In the words of Walter Benjamin: “We will arrive at a moment of sufficient self-alienation where we can contemplate our own destruction [as a species] as in a static spectacle.”

Richard Hornby’s antiperformative “metadrama” and other neorealist art theories that deny the performative aspect of personae, or the frame, populate contemporary art in pop and academic circles. The neoliberal subject has been split into the spectacle itself (a ticketed event, or occupied site, rather than a commodified subject), and an observer of and in spectator culture, passively watching the made-for-TV sitcom/soap opera/reality show not only of other event-sites. Gladman’s Event Factory (the first novel of The Ravickians, a series taking place in a fictional city in an invented language) as the new psychological novel? Hardly.

Beyond postmodern formalism lies connectivity (or the abandoned dream thereof): Gladman distrusts the power of authorial language to uphold meaning for a reader (the stabilization of a signifying code, allowing for communication: language’s original “function”). Gladman invented not just words in The Ravickians but a language, Ravic, to “say what my voice would allow me to say,” and rid her voice of the “vowel presence” of Spanish and English: “With a name like Luswage Amini, syllables get pronounced the way a black Southerner speaks. It’s like Lu-SWAGGE, kind of slow, drawn-out … I think black people and Eastern Europeans should have a conversation about possible overlaps between their experience.”

Likening the communicative restraints of the English tongue to a stiffening body, Gladman suggests how communication is conscripted by not only logos, but the grammatology of the language in which we are speaking or writing: “the subject-verb-predicate order enforces a pattern. Having the body as an extra means of communication is one way of addressing that limitation, but the body still imposes another kind of order. You age and can’t communicate because you can’t spend three minutes in a backbend.”[1]

E. M. Forester’s panacea for modernist nausea and anomie(“only connect”) strikes the postmodern auteur as hopelessly naïve, yet narratives of isolated suffering and disconnection (heightened in cyber culture) dominate American media, as we arrive and depart, yet rarely connect, during travel, and only at a temporal remove in reading. The flexible labor of geographically mobile subjects (fully wired and easily transplanted) may adapt us to the workplace and urban living, but what is the “added value” (or hidden cost) of not connecting with a writer, or reader, or, in reading (or writing), failing to make connections or understand?

The lines between past and future, as well as cultural and racial fixities, dissolve from solid to liquid in Gladman’s story “Calamities,” a text whose armature is performance: “There’s this feeling that there is a community or interested parties who are reading these essays, because they are also junior faculty or are also living in lonely cities or also have a crazy idea, like that black people could be Eastern Europeans.”[2] The fetishization of aesthetics over labor, of capital over art, extends to the fetishization of the text: written language’s trace of presence rather than “real presence” of speech displaces the difference of the other, beginning with the authoritas denied God the Father and the narrator (Sartre’s dreams of totalized meaning) and ending in simulacra, or witnessing of the “untruth” of texts removed from structural laws (linearity, progression, meter, authorial intent, and time). “The truth of writing is the not-true,” as Alice Jardine says. “Writing is … the supplement in motion: liquid, inconsistent, imp-proper, non-identical to itself, it menaces all laws of purity.”[3] Including, apropos to Gladman’s work, the purity of genre and classificatory essentialisms regarding race, ethnicity, and other taxonomies of species and culture. Paradoxically, the supplemental trace marks of the absence of presence: lack rather than meaning as the condition of thought and experience, and self-alienation within representation (the written text) bearing the necessity of its own deconstruction and critique.

Whether the staged interiority of a monadic “I” is in conversation with an interiorized “Thou” (and, in the history of Greek drama, the collectivist, or royal, “we”) and is an a priori construction projected, as W. R. Johnson believed, for a reader, or whether the work of the lyric is the staging of that self, tempt questions of cultural representations of the graphic “sign” (mark, character) and the word, as differentiated from voice, and, in many Indo-European and Gallo-Romantic languages, the split between sign and referent. The “absence” of presence, attenuated in narratives wherein a new tongue is out of necessity invented, transcends the catch-22 of unrecognition or invisibility (lacking signification) or, risking speech, only to be reappropriated and resignified by canonical “authority” or a hegemonic race, class, or gender.

The trace, as an epitaph marking the lost object or memory, goes by several names in Jacques Derrida’s work (differance, arche-writing, pharmakon, specter): Derrida was also interested in the “gothic rhetorical effects” of encryption, paralysis, violation, and unspeakability, employed to “vex topological distinctions” through punning, and remains, since Plato, the most significant thinker on dialectic between the privileging of the text over orality. While it remains a mere supplement or index to presence, it “cuts” through the dream that there was an ontological presence, to which the infinite drift (the elided chain of signifiers not originating in or ending in a transcendent signified) refers. Language games, whether poetic or narrative, written or spoken, are speech acts, intention or not, with socially consequential and transferential implications: “I am listening” also means “Listen to me.” Or, as Jonathan Culler notes, a “work has structure and meaning because it is read in a particular way, because […] properties, latent in the object itself, are actualized by the theory of discourse applied to the latent act of reading.”[4]

Ironically, in today’s “New Narratives,” the building blocks of language, rather than communicative dialogue, perform a form of theatricality feigning indifference from an audience. This alienation is revealed in the paratactic “anti-cartography” of Gladman’s prose: at ease with dislocation, in rejection of totalized meaning and the responsibility of the auteur to serve as authority or guide. Gladman creates dense paratactic webs of relation, language, and plot, further complicating rather than streamlining or theorizing these contradictions (Barrett Watten’s Total Syntax, for example, nods to a patriarchal lineage of writers including Olson, Zukofsky, and Pound attempting to create a master-code or ur-text to embody language and its rule-sets to address the paradox of how language generates meaning, if meanings prismatic and in flux). Gladman’s writing process is one infinite drift, lacking formal closure or even dialogue: “I don’t have to end them … I would hope that through the accumulation of attempts to understand myself in particular experiences, maybe I would be something. That would be the self, an accumulation.”[5] Gladman’s disseminated speaker, sans self, thus laments: the map is missing, and even if we had one in our hands, would we follow it, even if being able to cognitively “map” our environment, personal history, or historical time?

For Gladman, epistemology is subject and site, as is the urban imaginary, or what Adrienne Rich calls the politic of location. The map figures largely in The Activist, a novel whose chapters include “Tour,” “The Bridge,” “Radicals Plan,” “Never Again Anywhere,” “White City I, and II,” driven by the question “Why is the map mutating?” and, later, despair (“The map has become everything to us, yet we can’t control it”). Capital’s liquidity is a literal metaphor for Gladman, who describes modern consciousness as a kind of freebasing on isolation, in “Juice”:

When my faith returned all my lovers were gone. That morning I woke to the two hundred and thirty-second day of the crisis; I was beneath my bed … lonely, but I was also sure. Life without juice had taken on the name and shape of my weakest character, who — when we passed on the street — did not know me. I knew it was me by the way my head felt: people find themselves in an idea and feel so specified by the idea that they are compelled to show it. Today all my ideas are liquid. That day of my faith, friends thinking I was sick came by … The juice on my mind was no longer juice. There was an absence there, but one so constant it became familiar. I did not want to drink it.[6]

Gladman’s anti-epic stance (a literal form of self- and other-leveling) expresses the body, and the denial of grand narrative’s distancing from temporality (and any perspectival judgment on one’s surroundings, based on a priori or theoretical “knowledge” distinct from, or as inextricable from, empirical experience). In this way, Gladman illustrates viscerally the inability to fully sever text from context, or form from content, questioning whether abstracted, reified, disembodied meaning (the decontextualizations of formalism and neoliberalism) can even be considered meaning, given the first order of alienation — representation — as such. “I was most interested in experience — how you obtain it, how you ‘capture’ it — but what led me to poetry rather than fiction, where experience is captured all the time, was a need to slow the whole thing down, to draw out the moments of experience, expose the gaps.”[7] In Event Factory (wherein an outsider struggles to physically orient herself in a city) and in The Ravickians (wherein a novelist struggles to represent that city), Gladman first sensitizes us to the politics of (mis-) translation before announcing the solution to mis- and un- recognition of otherness (the abject, foreign, or unassimilable subject into the maw of globalized English, and capitalism) to be the creation of a new, or forgotten, language: art, its forays into the unknown, outside of Hegelian sublation, market determinations and codified laws, a “language” immediately understood (i.e., in no need of pricing or translation) by a reader versed in encryption of truth. Metaphor incarnate, the trick mirror of potentiality as well as the actual weight, and worth, of relationships, the journey through sprawling mazes, of, and in, to life.

1. Renee Gladman, “The Company That Never Comes,” interview with Lucy Ives, Triple Canopy (January 30, 2012).

3. Alice Jardine, Gynesis: Configurations of Woman and Modernity (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986), 146.

4. Jonathan Culler, Structuralist Poetics (New York: Routledge, 2002), 113 .

5. Gladman, “The Company That Never Comes.”

6. Gladman, “Proportion Surviving,” in Juice (Berkeley: Kelsey Street Press, 2000).

7. Renee Gladman, interview with Joshua Marie Wilkinson, The Volta 7 (July 2012).