Becoming-language

On TC Tolbert's 'Gephyromania'

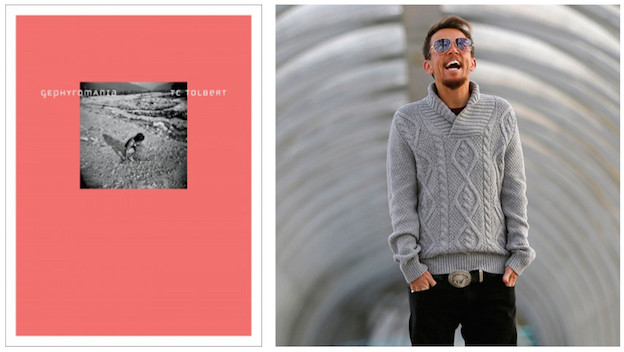

Gephyromania

Gephyromania

TC Tolbert’s poetry collection Gephyromania plays with, problematizes, and bridges various subjectivities and concepts of the body, identity, and text. Throughout multiple readings, Tolbert’s language creates a sustained state of anticipation, evoking a feeling of bodily movement (in both reader and author) not inappropriate for a volume whose title refers to an obsession with bridges. A bridge both separates and unites, just like a long-distance communication. What follows here is a review in the form of an unsent epistolary blast. As a friend of the author, my own problematic subjectivities are candidly referenced here, and the distanced eye of critical writing has been deliberately abandoned.

Message 1 6/26/14 11:15 a.m. CST

TC, it’s Jay. I’ve got your book and I want to open it out and mate it with mine, what I’m working on now, but that can’t happen. You know what? I wonder about my discomfort with speaking/languaging from within my own subjectivity. There’s something I mistrust in that, in myself. Or is it fear, the fear of punishment? My obsession with self-correction as a way to forestall the aforementioned. And how I would insist that my own transitioning is not self-correction. Do you agree? You say,

I want to tell you about my body. About testosterone

as unwitting art historian. About recovery. Me(n). What it feels like

underneath there. The part you cannot know. but should. (42)

I want this too. How can I trust this want in you but not in myself?

Message 2 6/27/14 9:15 a.m. CST

So I’m reading Judith Butler’s The Psychic Life of Power,and in her introduction she says, “[e]xceeding is not escaping, and the subject exceeds precisely that to which it is bound.”[1] It seems to me that this is what Gephyromania is “about,” if you go for that word in talking of your work. The challenge of time is present here in these poems, living as/in/with a body through time, a body in radical transformation as the medium of time flows about you. And you, in transitioning, have exceeded (not escaped) the embodiment from/with which you began. I make this connection without implying that “escape” was ever part of the goal, which I can’t claim. But exceeding happens, whether intended or not. And you’re still a body, you still must live in the tricky enclosure of your body. Me too.

This “bridge” place you build and use in the book — one goes back and forth on a bridge and maybe that’s the point too, or part of it. Not that you would (or could) go back to the embodiment from which you started, but rather, that body is also still in/with this body. You say,

You have forgotten that I do so little

with the skin I’m in. You make me a ladder

and now I want you to make me more. (30)

I’m not imagining a person as the “you” every time that pronoun arises, but when it does, here, it allows me to imagine the “you” empowering the creation of the bridge you travel, perhaps the bridge you become. There is a way in which we become bridges, isn’t there? Still anchored to — bound by — where we began and what we were then/there. And this is not “failure.”

Message 3 6/29/14 7:40 a.m. CST

So are we casualties of good advice, the same advice delivered deadpan to us again and again as though it were scripted? How to be a poet, to be a queer trans wo/man of any/all gender — can anyone really claim to know how to do and be?

Yeah, yeah. Pound, whatever.

Goddamned well of loneliness. Make it new. (76)

This is where we come from. Does where we originate actually help us bridge? Help us move? Help us change?

If there is not here

there’s a line I crossed. Somewhere valence

got Prufrocked with the T. (30)

There’s much to be said for the problematized power of others — maybe peers of who we were, maybe anticipated peers of who we’re becoming towards — to help with deciding and discovering how we locate ourselves, how and where and to what/whom we connect. But it is also important to problematize the origin-point of the poetic body (the embodied poetics?) in a space of high-modern text experiment. It’s an origin, I mean to say; I read in these poems an acknowledgement that there must always be many origins to the becoming-bridging. If there’s a range of poetics that can be called trans and genderqueer (within which we met), can we also posit a range of poetics that can be called transitional? Or is that rather limited word encompassed by the “trans” of our understanding?

Someone like Stein, living a queer life though not perhaps a “trans” life, somehow still managed a transitional poetics by exploding the documentary or utilitarian function of language. I’ve come back to Stein lately, which actually shocks me, because somehow I carry this idea that an understandable poetic framework for my particular masculinity relies more on looking around at, say, Kenneth Goldsmith or K. Silem Mohammed[2] than back toward a modernist icon like her. But what was Stein’s on-paper gender anyway? I don’t hold with the idea of masculine or feminine writing — this is a contradiction in me, as I clearly do embrace the idea of trans writing. That there can be such a thing that emerges in and from a text. Maybe what I mean is that there’s something about being trans that makes the word language into a verb. “And who wouldn’t/language in whose voice” (30).

I think this phenomenon is the manifestation of our exceeding the “good advice” we were given. We can no more escape the bonds of language than we can escape the born-in body. But we language ourselves anew, and our bodies force language to exceed itself. The question of whose voice is never resolved. The voice is multiple, and should be. This is why I never left Tzara behind, because he also languages. Makes a body with fragments of text, and calls it the approximation it is, calls himself the approximation any person necessarily must be. Perhaps not trans-identified, still he had the courage to bust the lid off of the idea that the self is singular and whole, proposing that whatever we are, we are not born but made.

Message 4 6/30/14 10:20 p.m. CST

It’s storming; fat waves of rain pound down on the roof, against the windows. Thunder coughs in the distance. Tomorrow early I have to go to diabetes school; I was diagnosed a couple of weeks ago, after my latest bloodwork for T levels. Transitioning has saved my life, in more ways than one, but often when I get healthcare I’m putting my head in the lion’s mouth. Someday I’ll tell you about my mammogram.

The thunder is closer now and the lightning more violent. I’m glad for your “A Love Note for My Breasts (Abridged).” Here’s the whole thing because I love it so much:

Thank you for the joke about Tokyo. I’m cutting you off now. For my grandmother and the way she talked about my grandfather. She said he liked her for her big brown eyes.

Thank you for protecting me from straight women. I’ll miss that. For making me think long and hard about why there was a marriage I was leaving. For the 1997 I never had. (28)

I think this gets me because of the way it speaks of forbidden things, or at least speaks of things in a forbidden way. I want to claim more of the not-nice; you know, the things not said or done in polite company, whatever or wherever that is. “I’m cutting you off now,” said in a poem for one’s breasts — but of course, that’s only shorthand, dancing with the popular idea of what embodiment is, means or entails for transmen. This phrase bridges the vast space between “mutilation” and liberation, a space made public in a process of dubious consent, by other people’s publicly expressed affects: revulsion, acceptance, hostility, pride. But “cutting off” is also a way to describe ending a toxic or abusive relationship. I hear liberation in it, ambivalence too, or irony — “protecting me from straight women.”

Is it your actual body that’s written in — or into — these poems? Is this something you can say came with or out of subjective experience? Because I find myself responding to your words more literally than I usually do for poetry, as though the narrator’s voice is your own, making a claim for the bodies contained in the book. I find myself doing that thing with your work that I do not want people to do with my work — I’m identifying with the poet. But I am also wondering about the question turned inside-out; that is, do you see the writing of the poems as part of the process of forming your actual body, beyond just reflecting it?

Weird question, and one I can only ask another poet.

Love,

Jay

1. Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 17.

2. That is, I expected my poetic masculinity to lean more on the “post” avant-garde than the “modern” avant-garde.

Edited byLaura Goldstein Michelle Taransky