Against apocalypse

A review of Ron Silliman's 'Revelator'

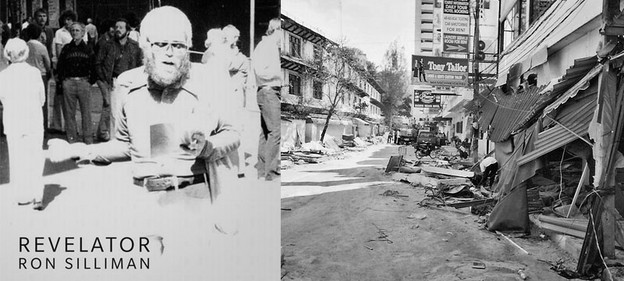

Revelator

Revelator

Somewhere along the way, Ron Silliman and his fellow L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets earned the reputation for being heartless. In the absence of lines like “I fall upon the thorns of life! I bleed!” and without understanding the historical contexts to which L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E responds, it can be hard for the uninitiated to identify emotional elements. After all, a poetry movement concerned with human rights, poverty, and opposition to violence can’t be entirely without sentiment.

Although he hits as heavy with theory as his peers (cf. The New Sentence), Ron Silliman’s work, like Lyn Hejinian’s (My Life), is saturated with first-person narrative, love, and nostalgia, notably in works like Ketjak (1978), “Albany” (1981), and The Alphabet (2008). Revelator fits within this strand of “slant” personal narrative.

A “revelator” is someone who reveals — in traditional uses, someone who reveals the word of God, specifically “John the Revelator,” who recorded the Book of Revelations. Due to the social context of his poetry, we can assume that Silliman is neither God nor God’s transcriptionist, but (as Gillian Welch’s revelator isn’t Blind Willie Johnson’s) something else, perhaps Ron himself, pictured on the front cover of the book reading Ketjak with a 1970s revelatory spirit, or perhaps, as Welch puts it, Time.

The jacket copy positions Revelator as “a poem of globalization and post-global poetics” that “addresses the problem that there are only two global systems: the biosphere and capital, while every response to these global systems is invariably local.” On the first page we get a hint of the political arena and the speaker’s desire for a total, but seemingly out of reach, reform:

… “Outsource Bush”

Against which, insource what? Who

will do it? … (9)

And again shortly after, the speaker’s personal response to the dire political situation of Bush’s presidency, again with an underlying sense of the total failure of the system:

… at Monticello I

very nearly wept, to imagine

just once the president as

the smartest, most questioning, most

rigorous of all … (13)

Amid Silliman’s panoply of motifs (bird-watching, taking the dog for a walk, aging) the cultural context of a global system where the “center cannot hold” emerges in descriptions of the war in Afghanistan, Fox News, Chipotle burritos, McMansions, and other contemporary economic and political references. The speaker’s mind, a tight fabric of many threads in close proximity, lets alternating images warp and weft, a concern for labor and markets freely woven with more personal thoughts: “peel cellophane / from a new tea carton / no indication where it’s grown / (Argentina!) no record no ____ / sense of the map” (32–33). Like Joyce and Zukofsky, Silliman uses the dense narrative to record himself as he records a specific moment in time and comments on its (sometimes overwhelming) social and political problems.

Again referring to the jacket for entry points, David Melnick calls the writing “friendly” while Roger Gilbert says it’s “fun,” and C. D. Wright goes along with the gag, using the term “witty.” I’ve never had a very good sense of humor, but I don’t find Revelator to be so carefree; I do find it to be warm, sympathetic, and humane. Consider the following passage, where at least four narrative threads converge:

for days the networks discover

new amateur videos, waves far

greater than one can imagine,

on the beach bathers not

even thinking to run, buses

floating through streets of debris

Banda Aceh, this week’s geography

of the public imagination, Phuket’s

stream of tourists washed away,

bulldozers scooping corpses, our newscaster

alone in an empty village,

only the battered mosque remains,

where are the people, how

does this outer life, apocalypse

reported, penetrate my dreams, three

men on the street walking

discussing who will reach 60

when, the way as teens

we spoke of 20, not

even seeing the homeless woman

asleep beneath the newspaper racks

at Mission & Fourth, fifth

of bourbon warms, warns, passed

between three beneath the bridge

day is done, day is

the ever-present challenge, wake

or not, the painter Jess

simply stays asleep. … (20–21)

The speaker watches the coverage of the 2004 tsunami; men who may or may not be the speaker and his friends discuss aging; a woman is homeless in a heavily traveled district of San Francisco but no one cares or even notices; three people of undetermined status share bourbon under a bridge; death; Jess, Robert Duncan’s partner, who died “of natural causes” (but not, as those in the South Asian tsunami, “of nature”). This passage has many motifs that appear elsewhere in Revelator: TV coverage of international disasters; the sense that the speaker is aging; an awareness of (and perhaps guilt about) extreme socioeconomic disparity; the threat of death; strong mental ties to the process of writing and to the literary community. The revelator is haunted by scenes of unnatural death, and often — in scenes where TV coverage speaks of American wars — personally haunted by his tacit responsibility for them. On the microscale, he’s aware of his own death and the mortality of his personal community. None of this seems particularly “fun” (Gilbert), but it does reflect a “desire to pull everything in” (Wright) and to let it flow forth in an open-mouthed tangle of record and revelation.

Time, which eats its own children, wants to pull everything in, and Silliman’s revelator fights back with the same weapon. From the most dear and personal to the anonymous televised global community, we are all mortal, and we all “rage against the dying of the light” quixotically: “I scream, you / scream, we all scream for / that which is unnamable, unquenchable, / inconsolable (deep in one’s chest / surrounding the heart) art is / a mode of stalking, balk / at any configuration, at what’s / inescapably omitted” (12–13). Silliman’s artistic desire to pull everything in, to mark it, to keep it against the threat of global and personal apocalypse, makes this a work of what Martin Hägglund calls “chronolibido”: “Poetry engages the desire for a mortal life that can always be lost.”[1] Silliman writes:

Dear Krishna, it’s 6:11 A.M.

upstairs a faucet turns briefly

Lilly is grown now, Alan’s

hair thins at last, Melissa’s

perfect smile still shines but

no sign of Lulu, time

erodes what’s dear, what’s near

is past too soon to

grasp fully the consequence, dawn

threatens a new day constantly

sun as vicious as dusk

or rather simply uncaring, birds

disinterested in the infant’s corpse,

it’s language that introduces emotion

or the other way round (23)

The revelatorhas multiple levels. He warns of the violence of global markets, war, environmental collapse, and socioeconomic inequality. He warns of personal apocalypses: deaths among his personal communities, marks of aging, and his own demise. These are godless revelations: we’re already in the apocalypse; there is no afterwards. “Revelator is the opening poem in a major sequence entitled Universe. It’s the jumping off point for a work that, if Ron Silliman were to live long enough, would take him three centuries to complete” (book jacket). We know Silliman cannot write the whole universe — but his intense desire to take a snapshot of our mortal lives, to “pull everything in,” provides a haunting, dense, breathless battle against Time “coming to take its breath away.”[2]

1. Martin Hägglund, Dying for Time: Proust, Woolf, Nabokov (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012), 2.

2. Jacques Derrida, The Work of Mourning (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), 143.