The space of the imagination

An interview with Lisa Jarnot

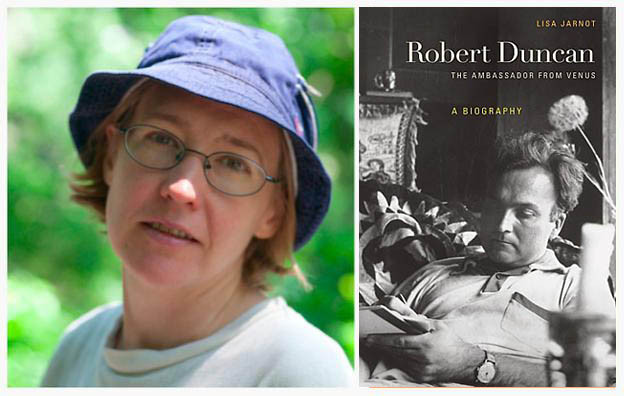

Note: Lisa Jarnot’s magisterial work on the life and times of Robert Duncan, The Ambassador from Venus, is an important and much-needed text. Apart from being the only full-length biography of the poet, it is a rich and dense document of literary and cultural criticism, which places Duncan within larger social and historical contexts. As literary biographies go, it merits comparison with some of the best: Richard Ellmann’s James Joyce, Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era, and Hermione Lee’s Virginia Woolf come to mind. The Ambassador from Venus will become essential reading for those who want to understand Duncan as both a person and as a poet. I recently met with Lisa to discuss the biography, Duncan’s life, and poetry in general, and what she plans on doing next, now that the fifteen-year odyssey of researching and writing is over. — George Fragopoulos

George Fragopoulos: Long before you started working on the biography, you were interested in Robert Duncan’s work. Can you say something about your early relationship to his poetry and work?

Lisa Jarnot: I worked at the Poetry Collection — the rare book archive at the University of Buffalo, SUNY, when I was an undergraduate and a work-study student in 1987. That was also the year Duncan’s papers arrived. Duncan had sold his materials to pay for his healthcare costs due to his kidney failure, and his papers arrived in waves. I read all eighty-one notebooks and made an index of what was on the pages. It was unusual work for an undergraduate, but it was due, I think, to the fact that the curator of the archive at the time did not want a graduate student to do it. He didn’t want to have someone working on that material with professional aspirations, so he let me do it.

So I knew Duncan’s work inside out and was totally fascinated with it. As a fledgling poet, I was already interested in Allen Ginsberg’s work, but here was Duncan — a poet who was very different from Ginsberg. I mean, Ginsberg was this crazy, far-out, Beatnik poet, and Duncan was this genteel, domestic, middleclass poet. The contrast was huge, and the poetics held a big contrast as well. Ginsberg had that huge, sloppy Whitmanesque line that was filled with all these pop-culture references and Duncan had all these references to nature. I read Roots and Branches and thought Duncan was a nature poet or something; I couldn’t really make much sense of it. I actually thought at first it was kind of stupid. [Laughs.] It’s not his strongest book. But Robert Creeley was also at Buffalo and was teaching a graduate seminar on Duncan and Olson and Ashbery that he let me sit in on. He was covering most of Duncan and Groundwork. The fact that Creeley was [teaching] Duncan and thought he was great made me want to know why. At first I wasn’t convinced, but everyday I would go to campus and sit and read Duncan’s notebooks. I was saturated in it.

Fragopoulos: Your biography really makes great use of the archival records. For example, you bring to light the fact that Duncan spent a good portion of his early twenties working on a novel, “Toward the Shaman.” What remains of that in the archive? Did he come close to finishing it?

Jarnot: That’s in the archival material out in Berkeley and I would have seen that stuff later, around 1989 or 1990. There are six notebooks, from about 1939 to 1942, that contain all that he worked on for the novel. He sold those early — I’m not sure why — and all the rest of the stuff he held on to until he made the sale to Buffalo.

[The novel] would have read like Anaïs Nin’s diaries [had he finished it]. It was lots of fragmented stuff, really juvenilia. It was self-analysis, more or less, the kind of work he would have done had he been in analysis. It’s not really that interesting.

Fragopoulos: You also quote extensively from his letters, but we really only have his correspondence with Denise Levertov in its entirety in publication. I’ve always wondered what his correspondence with Creeley is like, for example.

Jarnot: The interesting correspondence is the one with Jess. There is a real hashing out of poetics there. The correspondence with Creeley was less interesting to me; there is a lot of business being discussed there, because Creeley had university positions and was able to arrange gigs for Duncan. But with Jess, it’s different. When Duncan is on the road and is about to give a talk or lecture, he’s writing to Jess about what he’s thinking about. Those are pretty intense letters.

Fragopoulos: Speaking of Jess Collins, Duncan’s longtime partner, your biography at times is almost as much about him as it is about Duncan. Jess was an interesting artist and an emotionally complex person in his own way. You didn’t get a chance to meet Duncan, but you did meet Jess. What was he like?

Jarnot: I met Jess in August of ’88 and we had lunch together. I moved out to San Francisco in ’89. I would see Jess every now and then, and we would have lunch or dinner together. He was very shy and didn’t let too many people into the house. I think he let me in for a couple of reasons. One, I was a girl. Two, I was also shy. I was non-threatening in a number of ways. My shyness didn’t make for a deep relationship. We mostly talked about the lemon tree in the back yard, and about cooking. I asked him a ton of questions about Duncan and Duncan’s friends, which in retrospect, probably wasn’t that interesting to him. But I saw what that household was like. On the occasions I was there, Jess let me look around. And when I started the biography, he let me photograph the house and all of the bookshelves. It was a great education. The first time I was there, he cooked me chicken livers, and I was horrified by it, but it was great. We went through their record albums and listened to a Stravinsky recording. And I was so shy and had to pee and I couldn’t even ask to use the bathroom. I had to leave before the recording was over! [Laughs.]

I’m kind of glad I didn’t meet Duncan, because I feel it could have affected the biography. I had a neutrality. I always say that if I ever write another biography, it would be of Stan Brakhage; but I knew Brakhage, and think that would change my writing — I admired Stan so much. But I’m glad I met Jess. He was so emotionally complex. There was a part of him that was like an old Victorian aunt. He was almost prim, and he was very unanalyzed, unlike Duncan. Duncan knew his own psychology inside out. Jess was more shut down. In psychoanalytic terms, he had a huge split. He either loved people or hated them. You could ask him about Jack Spicer and he would say, “I hate Jack Spicer!” and, you know, Spicer had been dead for years. There was something entirely childlike about him.

Fragopoulos: Was he still creating art at that point in his life?

Jarnot: Yes, when I met him he was working on one of the Salvages, the one with the eagle in it, I forget now what it’s called — Torture the Eagle Until She Weeps? He was also working on jigsaw puzzles to add to collages. When I started the biography in 1997, he was doing okay, but it was the beginning of Alzheimer’s. When I saw him in 2000, his immediate functional memory was gone. He knew what happened in the 1950s, but couldn’t remember what he had bought at the grocery store.

Fragopoulos: So what made you want to write the biography?

Jarnot: I knew I wanted to do something with Duncan, and I knew I wanted it to be something substantial. I taught at the Naropa Institute in the summer of ’97 and Ed Sanders had given a lecture on book-length poems. At the time, Sanders was writing his long poem of the life of Allen Ginsberg, and his history of America in verse. He suggested I should write a biography of Duncan. Ed was really essential in helping me in many ways. He had developed research, organizing techniques that went back to the work he did on Charles Manson. My entire organizing system for the book was based on techniques that were drawn from him. For example, Ed had a way to cross reference files in three-ring binders so that nothing could get lost. I had index cards with subjects on them like “Duncan’s Mother,” or “George Herms,” whatever, and then boxes filled with these cards, and those cards were cross-referenced with files in the three-ring binders. It was a wonderful system. And I had about sixty of these binders. Ed’s idea was that you had to be able to find every piece of paper within thirty seconds. He also suggested things I would never have thought of — that I should look up Duncan’s FBI file or that I should write form letters to every university Duncan ever spoke at. I collected tons and tons of stuff.

Fragopoulos: Was there an FBI file?

Jarnot: If there was one, it was lost. I think there probably was one at some point. He was at the march on the Pentagon with Mitch Goodman and Dr. Spock, and he did speak out at anti-war demonstrations. I sent out a request and the FBI said they didn’t have anything. I wrote back saying, “you probably do,” and they reopened the search but still couldn’t find anything. I’m assuming he is cross-referenced somewhere — the same with his military records. I wrote to the army twice, but they said the records were destroyed in a fire. Duncan said he was dismissed from boot camp as a sexual psychopath, but the official record is gone.

Fragopoulos: For Sanders, the book-length poem form seems to have been influenced, in part, by Charles Olson. Can you say a little more about the Olsonian aspect that influenced Sanders, and whether this was something that you were also conscious of?

Jarnot: Yes, for Sanders the idea [for a book-length project] partly came down through Olson, but not so much for me. But Sanders and I were of like mind and it came down to a question of history. For me, it was about loving the history of the counterculture and being seventeen and learning about Alan Watts, Lenny Bruce, Bob Dylan and the Beats. The ’60s were so formative to me and my life as a poet. So what interested me, in the course of writing the biography, was finding those intersections, finding those moments where Duncan rubbed up against the history, and San Francisco was interesting for those reasons.

That is the greatest thing about writing biography: all those little things that you find, all the discoveries you make. I went out to find the ashes of Duncan’s adoptive mother at the Chapel of the Chimes in Oakland. Then I talked to his cousin Gladys, his biological mother’s niece, and she told me about the plot where his biological mother is buried and it’s within a stone’s throw of where his adoptive mother is interred! It’s in an adjacent cemetery. And Duncan never knew this. Or you go someplace where no one wants to go; it’s a mausoleum, a dusty old place, a very strange pursuit. Or going to Bakersfield, for example, to meet Duncan’s adoptive sister, Barbara, in what seems like the middle of nowhere, to see the movie theatre he went to in 1936 … it’s still there.

Fragopoulos: How difficult was it for you, as someone who primarily writes poetry, to write a biography — something that is totally different in terms of genre and style?

Jarnot: It was really hard. I wrote many drafts. It took fifteen years. The first draft was written as verse, or at least broken up into stanzas. I wanted to be able to have the dramatic entrances into chapters and I had to learn how to do that. My favorite biography is the Richard Ellmann James Joyce, and what I liked about that book were the really short chapters, and I had to convince the publisher [University of California Press] to do that because they were worried about the length of the book. I wanted to have the shorter chapters, like little vignettes, and I wanted to have the quotes before each chapter. I like dramatic intros, like Carl Sandburg’s Lincoln biography, which begins with the story of Lincoln’s grandfather being shot by the “red man” while working in his corn field, an epic movie opening. My original draft had the story of the [San Francisco] earthquake of 1906, but that eventually disappeared. I kept the story of the seemingly magical meeting of the Duncans and the Symmeses in Duncan’s Aunt’s Faye’s pharmacy; that was part of the original scaffolding. The first section was heavily written over and over again, but the section on New College was written early, and the chapter about the Zukofsky event altercation with Barrett Watten was as well, so I tried to keep as much of that as I could.

I wanted it to read like Capote, like In Cold Blood, which is so hard to do. Writing modern biography is so maddening because the record is so dense; there is so much material. You can track what somebody is doing every minute. And today, with emails and the like, I don’t know how people do it. Duncan was an obsessive record keeper. He was always on the road, so there are a lot of records of his actions from the universities he was at, and all the letters he was sending and receiving. And in the ’80s he was keeping a daily calendar of what he and Jess were doing every day. His notebooks are different. There are a lot of reading lists and reading notes; he didn’t have diary entries so much. So there was too much info. I could have easily spent another ten years writing. I have a list of things I never looked at. My copy editor helped trim it down. But trying to combine interesting prose with historical data is really hard. In some ways, University of California Press wanted me to tell the readers why he was an important poet and get it over with, but I was obsessed with the details of what Duncan and Jess were eating for dinner. So I had problems with the readers hired by the press. The manuscript went through a couple committees. One reader on the first committee complained that there wasn’t enough literary criticism in it. But there was a historian in the second committee, and he said it was solid as a book with intersections into history. And I didn’t want it to be a work of literary criticism. I wanted people more to get a feel for the personal context of the poems.

Fragopoulos: What do you make of the current moment in Duncan studies? It seems like there is a renaissance of sorts going on, what with last year’s The H.D. Book finally seeing “official” publication, your biography, and all of these new projects coming out this year as well …

Jarnot: I’ve heard it described as the beginning of a “Duncan industry.” I hope it’s not; I mean, I don’t think of Duncan as a commodity. Duncan’s selected interviews have just come out [edited by Christopher Wagstaff]. The H.D. Book is in print. James Maynard is editing the prose and Peter Quartermain is finishing the early collected works. So a Duncan renaissance? Yes, hopefully. I hear people now saying that Duncan is a great American poet and he’s never been that before. He’s always been a more marginalized figure — a regional poet? a romantic poet? But Ginsberg is a great American poet. And so is Ashbery. So that’s what I would love to see: for people to read Duncan on that scale. And for Duncan to be read by people who are outside of the “avant” world, because he was certainly there in the ’60s and ’70s, in all kinds of unusual places, rubbing shoulders with writers in a more conservative tradition.

Fragopoulos: So what’s next for you?

Jarnot: I’m rereading Duncan and teaching his work, especially Groundwork Two. There is some really beautiful stuff there. And reading-wise it never ends. I mean, you reread someone like O’Hara — and I love O’Hara, he’s one of my favorite poets — but you go back to the poem and you say, “I know that line.” You go back to Duncan and you are like, “Hey, how did that happen?!” You are surprised by what you find there.

Fragopoulos: Can we call it a density or depth to the work …? I find that in much of Duncan’s work there is a kind of spatial poetics at work. The sequence “A Seventeenth Century Suite” in Groundwork: Before the War comes to mind.

Jarnot: Yes, it’s a hermetic architecture; “the work must have recesses.” And there it is. It just shows up. In Ground Work [he] is trying to position himself in that space of watching the war. Last week in class we were reading that poem about Southwell and the burning babe, and there is that scene where Duncan is saying, here is Southwell and he believes so much in his vision of Christ that he is willing to give up his life for it. And there is Duncan, watching the Vietnam War and asking himself, “Where am I and where am I as a poet”? And, at the same time, what is he going to do about his relationship with Denise Levertov? Who, at the time, is moving in a different direction. It’s a real soul-searching poem.

Here is the thing with Duncan: You look on the surface and it’s very iambic, it’s just trotting along, very hyper-romantic, but if you look below, take it line by line, there is this huge attempt to confront just about everything in the universe, really. By the end of the poem he manages to come to some sort of conclusion about the nature of reality. I mean you can see why this would have driven the Language Poets crazy, because he so much believes in the poet with a capital “P.”

Fragopoulos: And this brings us back to the household, to the domestic space he and Jess shared together, because what also comes across in your biography is this incredibly intense dedication that both Duncan and Jess had to their artistic lives and to that space they shared.

Jarnot: Yes, but there are also drawbacks to the world of the imagination. When reality creeps in, you’re kind of screwed. [Duncan and Jess] shored themselves up in a house that was an incredible, imaginative space, but when the roof was leaving there was no recourse; there was no magic spell for that, especially after Jess fell ill. They really lived in the world of the imagination. Like Brakhage said, they were upset about the moon landing, because that was the space of the imagination suddenly being colonized by the real. And in their house you really felt like a participant in the imaginary, in the “made place;” it was an amazing place to be.