The crowd inside me

Michael Lally in conversation with Burt Kimmelman

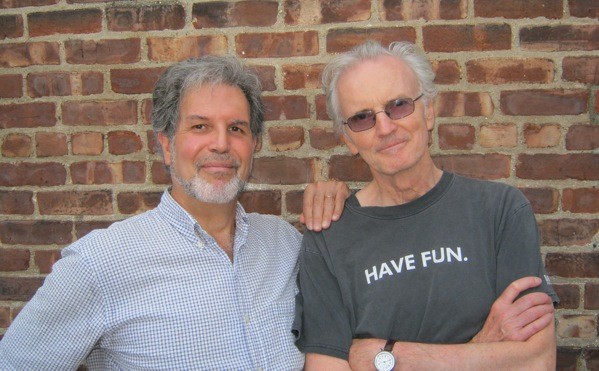

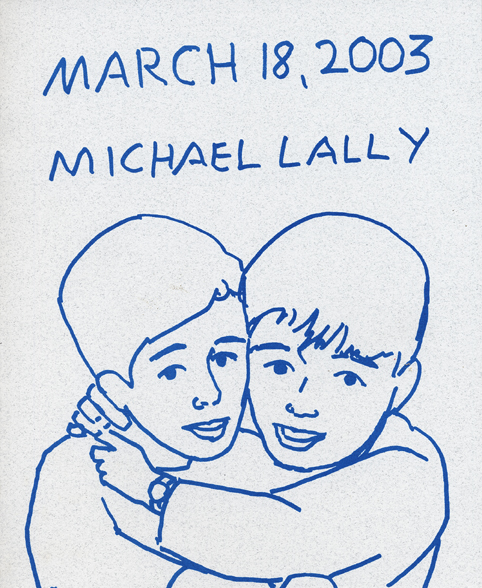

Note: Michael Lally is the author of twenty-seven books, including two collections of poetry and prose from Black Sparrow Press — one an American Book Award winner for 2000, It’s Not Nostalgia — and the long poem March 18, 2001, jointly published by Libellum and Charta, with artwork by Alex Katz. He is also the author of Cant Be Wrong from Coffee House Press, which won the Oakland PEN Josephine Miles Award for “excellence in literature.” He has appeared in many films and TV shows and worked as a scriptwriter, or “doctor,” from the late 1970s to the early 2000s. Recently a CD of him reading poems set to music, Lost Angels, was released by Monomania Records and is available for downloading at iTunes. This interview took place in the first three months of 2011.

Burt Kimmelman: Your life — at least as early as your jazz piano playing and then when still very young the publication of your first book, South Orange Sonnets — has been marked by intense creativity and a lot of artistic achievement: poetry, acting and so on. And your work has been lauded often (including an American Book Award). You haven’t played music professionally in many years, and since your recent brain surgery you have stopped acting professionally, but you continue on as a poet/writer. Do you see your respective careers, particularly poet and actor, as having been discrete, or is this really “all Michael Lally all the time”? I wonder if this question is not germane to any critical approach to your poetic output that is, at least for this reader, voiced and maybe really has to belong to a persona, one Michael Lally.

Of course you’ve written a lot — not just verse — and there is variation in what you’ve published. So maybe you see yourself as having produced a number of poetries or, let’s say, works of writing (there is your printed prose as well, and lately your blogging). This is an interesting notion — since you’ve been involved (centrally, peripherally, or somewhere in between) in a number of poetry scenes in your lifetime. What do you think?

I heard Elinor Nauen give a talk a while ago (at the Telephone Bar in Manhattan, as part of the Pros’ Prose series she and Martha King curate) about the East Village in the sixties, and she mentioned a magazine she coedited back then, a feminist publication whose each monthly issue featured a naked male poet as its centerfold. The monthly issue when you were the feature showed you masturbating. Would you say that this incident is iconic of your literary work overall?

Michael Lally: Complicated question, Burt, and based on some misconceptions I think. My interest and motivation have always been complex, from my perspective. I’ve written fiction (some included in my two Black Sparrow books, It’s Not Nostalgia and It Takes One to Know One, though I declined to distinguish it from other writing in those collections, leaving it up to the reader to discern which was “real” and which “fiction,” since both were based on my experiences and observations); and I’ve written criticism (I was a book reviewer for The Village Voice and The Washington Post back in the 1970s and ’80s for instance) and political journalism (I was a regular columnist for various, mostly alternative, newspapers throughout the late 1960s and early ’70s, and now write some political commentary on my blog, Lally’s Alley) and other kinds of writing that weren’t autobiographical in any obvious way. But I always took the admonishments of my early literary heroes having to do with writing about oneself seriously, as in Beckett’s “What doesn’t come to me from me has come to the wrong address.” And Dostoevsky’s “But what can a decent man speak of with most pleasure? Of himself.” And Whitman’s “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” etc. Or Thoreau’s “I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew so well.”

Michael Lally: Complicated question, Burt, and based on some misconceptions I think. My interest and motivation have always been complex, from my perspective. I’ve written fiction (some included in my two Black Sparrow books, It’s Not Nostalgia and It Takes One to Know One, though I declined to distinguish it from other writing in those collections, leaving it up to the reader to discern which was “real” and which “fiction,” since both were based on my experiences and observations); and I’ve written criticism (I was a book reviewer for The Village Voice and The Washington Post back in the 1970s and ’80s for instance) and political journalism (I was a regular columnist for various, mostly alternative, newspapers throughout the late 1960s and early ’70s, and now write some political commentary on my blog, Lally’s Alley) and other kinds of writing that weren’t autobiographical in any obvious way. But I always took the admonishments of my early literary heroes having to do with writing about oneself seriously, as in Beckett’s “What doesn’t come to me from me has come to the wrong address.” And Dostoevsky’s “But what can a decent man speak of with most pleasure? Of himself.” And Whitman’s “I celebrate myself, and sing myself” etc. Or Thoreau’s “I should not talk so much about myself if there were anybody else whom I knew so well.”

My original motivation as a kid was to express some realities I didn’t see represented in any of the arts I had any knowledge of (all of which — up until my mid-twenties when I was already married and beginning a family — was based on my own searching and autodidact reading). But in the process, and pretty quickly, I became equally motivated by the idea of “making it new” (as Pound prescribed), at least for me, meaning technically, not just in the subject addressed or delineated, but in the approach, the uses of all the linguistic devices I could discover or invent.

There were periods when others could see that, when critics and fellow creators told me or wrote me or even wrote in reviews about how original my artistry was during whatever period struck them as that, but as often happens when someone makes an abrupt change (a famous and well-worn example is Dylan going electric) they’d feel betrayed or just lose interest when I moved on to new discoveries or experiments, or encounters to retell and reshape etc.

That kind of shape-shifting and heart-following and new-direction exploring I couldn’t survive without doing. (Another favorite quote of mine that’s emblematic of a core drive, and also contributed to it, is a bit of the lyrics Jon Hendricks wrote for a Lambert, Hendricks and Ross version of Charlie Parker’s tune “Now’s The Time” — “If you be still and never move, you’re gonna dig yourself a well-intentioned rut and think you’ve found a groove.”)

I’ve often said “poetry saved my life” and I mean it. I was a driven man for most of my life, and still am to some extent, and part of that compulsiveness has been a kind of graphomania, where if I didn’t write on any particular day I would start to feel like a junkie withdrawing from his drug of choice, really really bad.

As for the photo of me in that Koff calendar, it wasn’t of me masturbating. But it was more posed than the others in it seemed to be. Though obviously everyone in it was posing for the camera, I just did it in a way that made it clear that this is a pose for a camera and I and the viewer are aware of that, rather than I’m pretending to be caught in the nude drinking a beer or whatever, as though I didn’t know the ladies from Koff were coming to photograph me in the nude today. (I asked if my lady of the time could take mine, since she was making her living then as a photographer — though she was actually a composer — but her takes were more like what ended up in that calendar from everyone else, so I had her teach me how to take the photo myself and got what I was looking for — and what Elinor was probably referring to was my telling her how in order to get the photo right I tried many tactics including at one point a little “fluffing” which I ended up accidentally getting on film because the camera went off too soon, though I didn’t use that shot — or the one that I had been doing that to set up — because it didn’t seem “posed” in the way I was going for.)

Part of all that was about “authenticity” — a label easily exploited and often misused I thought. The idea that Charles Bukowski, for instance, who worked for the Post Office, which granted can be, for some, a soul killing job (though I have family and friends who actually dug it back in those days) yet was for me the epitome of what I rejected from my childhood — the kind of safe and secure job my father wanted me to take, like my brother the cop etc. — so that I could pursue the life of an artist and live by my wits, that Bukowski was seen as an authentic artist of the rugged individual literary rebel loner type when he had a steady job and later made six figures a year from his books so he didn’t have to worry about jobs, the fact that he was taken as the gold standard for “authenticity” while the struggles of many others I knew — including mine to survive while raising children (mostly on my own) on my creative chops — could be seen by some as “selling out” (like my going into movies and TV as an actor at forty) originally bugged me and then amused me, the transparency of people’s desire to be conned but not want to have the con revealed.

I was into revealing that, my own, and fighting with every bit of my intellect and artistry to expose it and reveal as much as possible whatever “truths” I could at least approach if never quite reach.

Kimmelman: That’s a really funny story about the photo! Was that East Village scene a part of what you might consider your living authentically? And maybe in connection with how you were living: can you say more about the “realities” you “didn’t see represented,” as you say, when you were young, and how you responded to or with them artistically?

Was there a lack of “authenticity” you were missing, perhaps? I ask this especially given what you’ve said about Bukowski (the Bukowski industry maybe, in both poetry and film — I’m thinking here of the wonderful film Barfly, for example — two worlds you have been deeply involved in). Do you think too much was made of the need for “authenticity” in the sixties, looking back on that period now, one decade and more into the twenty-first century?

And maybe in this regard, looking back on Bukowski’s life, I wonder if one could plausibly argue that he nurtured what I’ll call a lived persona. What’s wrong with the “I” in poetry anyway? I guess actors are supposed to be extraverted and self-centered, while poets are supposed to be (should be?) introverted, and possibly altruistic (yes I know these are gross oversimplifications). If there is in fact a voice in your writing — indeed a consistent voice from one work to the next — particularly in your poems (as compared with, say, the purportedly selfless or subjectless, at times antilyrical, stance of Language writing — a movement you were at least tangentially involved with in its initial period), is that voice in fact a disguise or otherwise a subterfuge to protect the real or, to use your word, the authentic Michael Lally? Or are you disavowing the notion that there is a voice in your writing, authentic or otherwise?

Lally: By “living authentically” I just meant being honest about who and where I was in any given moment, rather than posturing or trying to create an illusion (I know guys who became cops or firemen etc. and still made music or did other more creative work, but they didn’t pretend to be anything other than what they were, that’s what I was after, not pretending I wasn’t ambitious or didn’t want as much respect and admiration for my work and efforts as I did, but also not pretending I was from anything other than I was or that I didn’t find a lot of literary theory and criticism totally boring and irrelevant in terms of how I experience(d) my own creativity and understood others’ (though I loved reading some of it when it stimulated my sense of language possibilities, one of my early favorite books being Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity, of all things). My point about the calendar was not to imply that the poets in it, which included Bukowski (why did he become such a major topic of our conversation?!), weren’t aware they were posing, or were pretending they always hung around naked on their roofs or wherever the photos were taken, but that their poses didn’t reflect the kind of consciousness I wanted to convey of “hey, we both know I’m posing for an unnatural photo of me naked so I’m gonna make the ‘posing’ part of this transaction obvious.”

I used to say about my work that I felt it was my job to make the subtle obvious and the obvious subtle.

As for the “realities” I “didn’t see represented” when I was a kid, here are a few examples. My family seemed to represent the stereotypical “Irish” (i.e. Irish-American) family. My father’s Irish immigrant parents lived down the street — she had been a “scullery maid” and he was the first cop in our town. My father was a seventh-grade dropout self-made businessman (home repairs) and part of the Essex County [New Jersey] Democratic political “machine” on our local level. My older brothers were a priest, a teacher (music), and a cop. My two sisters married a cop and a teacher (machine shop). I was the poet/black sheep.

We lived in a very small house not only with my maternal (and “crippled” as they said then) grandmother, but later with a boarder, and Irish extended clan members, either local or from Ireland, needing a temporary haven.

The few movies and books and plays and songs I knew that addressed the world of my family, often used these stereotypes, but they never reflected my experience of who these people really were, how they actually behaved and what their lives were truly like, i.e. unique (as I felt everyone I knew was, despite the surface obviousness).

For instance, my Irish immigrant grandfather — who kept a goat for a while in his backyard and drank too much after he retired as a cop — was totally unlike the stereotypical loquacious Irishman happy drunk. He was more like a Beckett character (which didn’t exist yet, at least not in my life) than something from Going My Way (which nonetheless I loved, as did my family, because Bing Crosby epitomized the easy grace with which we felt our best did their best).

Or my brother the priest, rather than like Bing and his “Father O’Malley” (or Pat O’Brien in Angels with Dirty Faces), my brother was inspired to become a Franciscan missionary to Japan after a stint in the Army Air Corps at the end of World War Two, feeling the spirits of the Kamikaze pilots had called to him, wanting him to save future generations of Japanese from thinking it was a good idea to kill yourself for an emperor (not seeing the irony of doing that by proselytizing for a religion that elevated martyrs to sainthood, though he quickly learned that few Japanese were interested in his “saving” them and so he settled into just being of service as best he could).

Where was that in any movie or book I knew of about the “Irish” or for that matter World War II?

And I could do that for everyone in my family and neighborhood, which was mostly “Irish” when I was little but by the time I left as a teenager included a wide variety of ethnicities, and always had a small contingent of African-Americans who’d been there long before the Irish came and who also on the surface seemed stereotypical but in reality were uniquely individual and unlike anything in literature or film or music I knew of as a boy and young man.

Michael Lally's South Orange Sonnets, front and back cover.

Initially my response to all that was to write as frankly and clearly as I could about life as I experienced it, the way the people I grew up around really behaved etc. But once I had done that to my satisfaction (of which The South Orange Sonnets was an early example) I then also wanted to convey how writing itself was uniquely gratifying and challenging and how it led me to desire not only to read a wider and wider variety of ways of writing but experience them in my own writing and discover my own new ways (which I thought I did, more than once, including writing that could have been classified as “Language Poetry” before that term and movement came about, and I know I wasn’t alone of course).

And I didn’t mean to use Bukowski as a symbol of the inauthenticity that disturbed me as a kid and later. Bukowski seemed to be true to his art and his intentions and did a pretty great job of it. (I wrote a very positive review of his latest Black Sparrow book for the Village Voice in the early eighties because they wouldn’t accept a review of the latest Larry Eigner Black Sparrow, claiming Eigner was too “obscure” and “unknown” — so they let me write a double review including the Eigner if the other was Bukowski.) But Barfly is a good example of what I meant. Any alcoholic knows that what was missing in that film were the times a drunk would piss or shit his pants or throw up all over himself and often others, and more aberrant behavior that the movie left out or glossed over. It romanticized drinking almost as unrealistically as the legends of other hard-drinking writers have, Fitzgerald et al.

As for too much being made of “authenticity” back in the sixties, I’m not sure what you’re referring to, but if it’s all the identity politics stuff, again it was the stereotypes that bugged me. I pointed out to college students when the Black Panthers, many of whom I knew and worked with, put them down for being in an ivory tower and needing Panther leadership and perspective in their politics, that it was college students for the most part, who were responsible for much of the antiwar activity and education of the general populace as well as for a lot of Civil Rights progress. Something I wouldn’t have known had I not been exposed to it personally.

My experience on the streets and going to college late on the G.I. Bill gave me a perspective that was pretty unusual and helped me see through attempts to pigeonhole and categorize any group or population and also made me want to expose the falseness of any generalities masquerading as analyses of “authenticity” back then, as well as ever since, and to expose my own faults and failings and phoniness when I recognize them.

I think “lived persona” is a pretty good term and that, yes, Bukowski did do that in many ways. As maybe I have too, trying on different identities (as others have pointed out, and me too [see “My Life 2”]) that I always felt, or came to feel, were part of the crowd inside me. As for “voice” (“voice” used to be considered very important when I was coming up in the poetry world) in my own writing, especially my poetry, I would never disavow it. As I said above, I was always, and still am, dedicated to getting as close to the truth in (and at) any given moment as is possible, at least for me. I made a deliberate choice when starting out as a kid to always write in a way that the kid I was and the people I came from could understand (I had the idea as a teenager that I could do for poetry what I thought Hemingway had done for prose, that clear, crisp, hardedged realistic perspective etc., at least the way I saw it then, but in fact if anyone did that it was Bukowski!).

Interestingly, after my brain operation a little over a year ago, I found myself unable at times to use the more simple, direct, conversational vocabulary I usually wrote and almost always spoke with as easily as before. Instead my brain would offer up alternative words when I couldn’t think of the one I would normally use, alternative words from the larger vocabulary in my mind from all my reading, and I’d find myself using terms I would never use and have always thought of as “phony” for me to use, like “pernicious” or “inelegant” or (actually I’m having a difficult time finding the best examples because they don’t come to me naturally, but rather unexpectedly, and often I look them up to make sure I’m using them correctly and I always am, which surprises me).

My point being, I now understand, post–brain op, that much of the way my brain (and I suspect all of ours) works is independent of so much I thought I had control over. Which in a way gets us back to where I started, with the compulsion to express myself through poetry and other creative ways we usually think of as some kind of “art” (which came from somewhere before my own consciousness formed because I can’t remember a time when I didn’t have that compulsion) and then through doing that the compulsion to find new ways and avenues and approaches for it, which led to results that gave me new pleasures that in turn generated new compulsions to discover even newer ways (for me) to do that (sometimes serially writing about the same experience but from different approaches and in different forms etc.).

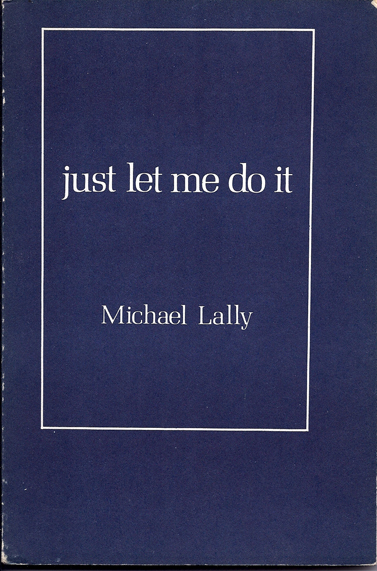

For instance in the late 1970s a selection of a decade’s worth of love poems was published called Just let Me Do It, in which every poem was formally different than every other one, no small feat I thought, and yet when Marjorie Perloff, a literary critic who’d written positively about my poem “My Life” in a review in The Washington Post of an anthology I edited, None of the Above, told me she admired an early book of mine, Rocky Dies Yellow (that also had a wide variety of approaches to writing a poem, including some I thought were uniquely my own), and asked to review the next one, which turned out to be Just Let Me Do It, she then told me she couldn’t write a review because she felt the poems in the collection were too formless, questioning if I made any deliberate formal choices at all (even asking if my line breaks were deliberate?!) I felt, not for the first time, misunderstood, as if because of the ways I chose to live my life and my commitment when writing about it to stick mostly with that simpler vocabulary — and because of my distrust of using a voice I felt would be inauthentic etc. — whatever “technical” skills I had were being overlooked and I was being cast again as the “diamond-in-the-rough” who had a few lucky moves but then reverted to type, rather than the evolving original I saw myself as.

For instance in the late 1970s a selection of a decade’s worth of love poems was published called Just let Me Do It, in which every poem was formally different than every other one, no small feat I thought, and yet when Marjorie Perloff, a literary critic who’d written positively about my poem “My Life” in a review in The Washington Post of an anthology I edited, None of the Above, told me she admired an early book of mine, Rocky Dies Yellow (that also had a wide variety of approaches to writing a poem, including some I thought were uniquely my own), and asked to review the next one, which turned out to be Just Let Me Do It, she then told me she couldn’t write a review because she felt the poems in the collection were too formless, questioning if I made any deliberate formal choices at all (even asking if my line breaks were deliberate?!) I felt, not for the first time, misunderstood, as if because of the ways I chose to live my life and my commitment when writing about it to stick mostly with that simpler vocabulary — and because of my distrust of using a voice I felt would be inauthentic etc. — whatever “technical” skills I had were being overlooked and I was being cast again as the “diamond-in-the-rough” who had a few lucky moves but then reverted to type, rather than the evolving original I saw myself as.

Kimmelman: I’m glad you like the notion of a “lived persona” and I do take cognizance of the fact that we are, arguably, all of us, many selves — a concept possibly more accepted today than in the days when you were first coming into prominence in the world of poetry and when (including identity politics), I dare say, authenticity became more important in people’s minds than it had been previously. Doug Lang has written about your work, associating it with the Beat movement — and wasn’t that movement in part at least a bid for the real, the authentic, in the Eisenhower postwar television-foisted era that sought to define itself in a myth of the perfect society? I don’t want to pursue this notion of the lived persona much further but, since I’m bringing up Lang’s commentary, let me acknowledge in passing that both he and Terrence Winch, who has also written knowingly of your work, have spoken of the “self-mythologizing” in it (of course one of them could have unconsciously absorbed the phrase from the other, but still, Lang also calls you “a performer” and perhaps dangles the possibility out there that yours is a self-performance). Frankly, I like the idea of a “crowd of voices” within you, of points of view or whatever. And I think it might be more useful to pay attention to Lang’s comment that you developed an “anti-literary version of American speech” and that, as you have put it, you “felt it was [your] job to make the subtle obvious and the obvious subtle,” and, too, you had no use for or patience with the academy, the “literary.” To be candid, while I see how you hold forth (on paper and in person when you read your work), how you declaim in a way that might be reminiscent of, say, a Gregory Corso or Allen Ginsberg, I think your poems at times strike me as of a language Williams might have written had he been alive in your adult life, or perhaps a Paul Blackburn (though his work is visually wrought in a way you seem not to be interested in); that is, your work is plain spoken and direct. It is also sincere though it sidesteps sentimentality, I think, for example in a poem like “Forbidden Fruit”:

all the forbidden fruit I ever

dreamt of — or was taught to

resist and fear — ripens and

blossoms under the palms of my

hands as they uncover and explore

you — and in the most secret

corners of my heart as it discovers

and adores you — the forbidden fruit

of forgiveness — the forbidden fruit

of finally feeling the happiness

you were afraid you didn’t deserve —

the forbidden fruit of my life’s labor

— the just payment I have avoided

since my father taught me how —

the forbidden fruit of the secret

language of our survivors’ souls as

they unfold each others secret

ballots — the ones where we voted

for our first secret desires to come

true — there’s so much more

I want to say to you — but for

the first time in my life I’m at

a loss for words — because

(I understand at last)

I don’t need them

to be heard by you.

There’s a tenderness here that one will not find in the Beats or in Williams, Blackburn, the Black Mountain poets (with Creeley or Oppenheimer as possible exceptions — but I don’t think they were so very, let’s say, heartfelt, ever). But what I find also remarkable is how unabashed your world of feeling is. Would it be wrong to think that in the blue-collar life you grew up in such open sentiment was suppressed? I like what Hirsh Sawhney has written about you: “Lally’s poetic vision is […] permeated by a spiritual optimism.” Indeed, you are not a poète maudit. Do you agree?

Anyway, beyond the few you have mentioned already, who are the poets and writers — and, while we’re at it, the actors — you have admired, and how do you see them figuring in your oeuvre?

Left to right: Michael Lally reading at Folio Books in Washington, DC, circa 1977, with Doug Lang and Terence Winch.

Lally: I appreciate both Lang’s and Winch’s takes on my “self-mythologizing” and playing with personas. A more recent and equally original take on that is Jerome Sala’s post on my poetry from his Espresso Bongo blog.

I like your take as well, especially your using the term “heartfelt” instead of “sentimental,” which I’m sometimes accused of being. And you’re correct that the kinds of feelings I write about were mostly suppressed in the clan and neighborhood I grew up in, except at funerals and sometimes when more than “a drop” had been taken.

I wasn’t as expressive of my feelings through most of my boyhood and young adulthood either, though more than those I came from, especially when it came to romance. As my good friend, the late poet Etheridge Knight once said of my work, even my “political poems are love poems.”

But the real breakthrough for me occurred after feminism and the “gay movement” convinced me that, as the feminists said then, “the personal IS political.” I was already partly there but these movements inspired me to go even further. The difference is obvious if you read my South Orange Sonnets — written before that influence — and My Life, written as the influence of those movements on my work was peaking.

And just an aside about your reference to Paul Blackburn and his use of space on the page. I did write more under the influence of “projective verse” or “open field verse” — as it was also known — before the changes that feminism and the so-called “gay revolution” inspired in me and my work, which led in part to my wanting to convey more of a sense of urgency and unrelenting rapid-fire persistence in “getting the truth” (as I saw and experienced it) “out.”

All of which occurred when I was living in DC from late 1969 to early ’75. I’d been writing and rewriting The South Orange Sonnets in different forms since 1960 when I was eighteen (they became sonnets after I read Peter Schjeldahl’s Paris Sonnets and thought, in my typical fashion, because I had never been out of the country at that point, that “Paris” seemed a little elitist so I’d write about the place where I grew up as far from what I thought Paris was at the time as I could get), but they coalesced into their final version shortly after I arrived in DC, with helpful input from fellow Iowa Writers Workshop and Midwest poet Robert Slater.

Mass Transit magazine cover, 1973, with Michael Lally, Lee Lally, Terence Winch, Ed Cox, Ed Zhanizer, Peter Inman, Tim Dlugos, and others.

One of the first things I did in DC was look for poets and readings. But everything I found was either too formal — readings at the Library of Congress where several times I stood up in the audience to raise questions or objections, which made a lot of folks uncomfortable — or salons in professors’ and others’ homes. So I organized some readings for benefits and then started a weekly open reading called Mass Transit — in the Community Bookstore I helped run — that attracted a lot of independent souls and poets just beginning to express themselves, including the not-yet-actress, let alone movie star, Karen Allen, the not yet rock’n’roll musician/singer/songwriter John Doe, who wouldn’t take that name until years later in Los Angeles, who was mainly a friend of Terence Winch’s, the poet and Irish musician/songwriter who became my best friend, and many others, like my wife at that time, Lee Lally, and Ed Cox, Ahmos Zu-Bolton, Tina Darragh, Beth Joselow, Tim Dlugos, Peter Inman, Lynne Dreyer, etc.

Out of those readings, a few of us started a poetry publishing collective, Some Of Us Press, which became known as SOUP, putting out a poetry “chapbook” every month by a local poet, including the first books of several of the poets mentioned above as well as poets tangentially connected to the readings, e.g. Bruce Andrews and Simon Schuchat. Many of the books sold out their small runs, giving us the money to publish the next one. Some were reprinted a few times (like The South Orange Sonnets, the first one we published, which went on to win me a 92nd St. Y “Discovery Award” for 1972, though by the time I did the acceptance reading there my life and poetry had changed directions once again and Harvey Shapiro, the judge who introduced me and picked my S.O. Sonnets to win this honor, seemed almost reluctant and saddened by my new direction).

Washington Post, article 1973 on Some of Us Press.

The best thing about being part of this self-created community that I helped generate, were the friendships and interactions, like Terry Winch not just becoming my best friend but giving me very helpful input after reading a long poem I was working on, saying, “I think the poem begins in the last few lines” which became the beginning of what turned into “My Life” — a poem that marked in some ways the end of my time in DC.

But to answer your main question(s): I already mentioned Bing Crosby, but in my boyhood it was him and (early) Frank Sinatra and Nat King Cole (when he still had a trio and played piano as well as sang), who introduced me to great lyric writing through their renditions of what became known as “the American songbook” that we used to just call the standards.

As others have pointed out, Bing was cool and Frank was hot but what they introduced into popular vocalizing in both cases was being conversational. Rather than tone and pitch and elocution as the markers for great vocalizing, a sense of intimacy and truth became equally if not more important. I got that as a boy, and was also moved by the sophisticated use of rhyme and rhythm and vocabulary in the great songwriters they interpreted.

Johnny Mercer was the first lyricist whose use of language I fell in love with as a tiny kid in the song “You Got to Ac-cen-tu-ate the Positive” — a philosophy that may have influenced what you quote Hirsh Sawhney calling my “spiritual optimism” (something, by the way, many critics obviously have a difficult time with in general, as shown in their championing of Burroughs over Kerouac, or Eliot over Williams, etc.).

I also may have been influenced by the romanticism in most of those great standards. But it was when I hit puberty, just as rock’n’roll began, that I saw a way for me to use what the great lyricists were teaching me, and that was in Chuck Berry’s closer-to-home lyrics, beginning with “Maybelline” (the title of my MFA thesis, a collection of poetry, at the University of Iowa Writers Workshop was “Sittin’ Down at a Rhythm Review” — a line from Berry’s “Roll Over Beethoven” I thought described a lot about my time there and a radical gesture in 1969 when the workshop still didn’t teach the New York Poets, let alone the Beats et al., and Chuck Berry and the other rock’n’roll and R&B innovators of the previous decade were mostly, if not entirely, forgotten or ignored). In the first poetry anthology where my work appeared — in 1969, Campfires of the Resistance — I mentioned the influence of Berry in my contributor’s note.

Not long after I first discovered Berry’s lyrics, I got into jazz — playing it and listening to it almost exclusively — and that’s where I encountered Jon Hendricks’s lyrics, taking the rhythmic and melodic inventiveness of jazz improvisation and applying it to my own poetry.

The first poets to influence and inspire me were Saint John of the Cross, Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson, followed almost immediately by E. E. Cummings, T. S. Eliot and William Carlos Williams, and then Diane di Prima, Ray Bremser and Bob Kaufman.

St. John I discovered in a paperback version of his Dark Night of the Soul I found on a book rack in the vestibule of my family’s parish church. I was a print junkie from the start and in the fifties when paperbacks were everywhere I devoured them until I began to find the writers and poets whose work seemed to speak directly to me and my inner life, St. John being the first.

Dickinson’s use of dashes, ignoring of conventional punctuation in order to get the rhythm of her thoughts down quicker, the way I read it, and the freedom and directness and clarity of her expressing her philosophy impressed me. The first Whitman I read was a paperback version of his prose masterpiece Specimen Days, a book I continue to reread and still find uniquely inspiring in its plainspoken articulation of personal experience (often in the context of historical events). But I quickly discovered Leaves of Grass as well and have been rereading the various editions of that collection continuously ever since.

Cummings mostly liberated me from a sense of shame for my sensuality and desire to express that through writing. I picked up on Eliot’s rhythms, which I found so musically proficient that it overwhelmed my natural chip-on-the-shoulder negative reaction to his otherwise conservative voice and posture. Williams was like my first “home boy” poet, reinforcing my own belief that the local was not just important but imperative in making any literature not only as “true” as possible but as relevant.

Diane di Prima gave me permission to speak from my family and neighborhood background while still being true to who I was becoming in the moment, and not to pull any punches (her Thirteen Nightmares I had almost memorized and used to quote on air at one of my early jobs as a disc jockey when I was still a teenager, and may have been the reason I got fired!). Bremser introduced me to how my naturally speedy nature could translate into poetry and Kaufman confirmed my belief in the power of jazz rhythms to propel my imagination into new forms of expression.

The other great influences were William Saroyan’s fiction; his autobiographical nonfiction when midway through his career replaced the fiction; and his plays. Here was a fellow autodidact (as I saw myself at the time), the relatively poor son of immigrants growing up in that kind of insular immigrant community and mentality, yet rather than being intimidated or critical of those outside that community, instead identifying with every kind of human (and creature), believing he could see himself in it all and having an unshakable faith that what he had to say about that was important and necessary … I could go on, but will just say I felt Saroyan was expressing some of the same feelings and thoughts I was trying to express in my own writing back then.

Kerouac had a similar effect. I identified with his ethnic and cultural minority background, transcended like Saroyan and me by a love of writing and books and a sense that there was a perspective that hadn’t been represented in the world of literature yet that we were born to accomplish (perhaps a little arrogant on all our parts and obviously more so on mine since I didn’t fulfill that anywhere near on the level they did). But I was also drawn to their peculiar mysticism (especially Kerouac’s Catholic influenced version, closer to mine) and their refusal to accept their intellect as in any way less than those who would criticize them for seeming too “raw” or “sentimental” or accuse them of somehow not really knowing or controlling what they were doing, like they were spewing rather than crafting their prose (they also both wrote poetry but Saroyan’s was pretty weak while Kerouac’s was much more unique and ultimately very influential).

As has been proven posthumously for Kerouac, he did indeed craft his prose and make deliberate choices in his attempts to get closer to realizing his personal ideal of what great writing should accomplish in his time, but while he was alive there were few critics or literary figures who took the time to discern this, most of them dismissing his work as too unpolished to be comparable to “great literature” etc. (The famous putdown by Truman Capote is a prime example of that, where he said something about how Kerouac wasn’t a writer, he was a typist — I can’t remember it exactly because I never liked it and because it was wrong.)

There were a few other early influences, like the probably obvious James Joyce, whose Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, especially the opening pages, had a major impact on my sense of what could be done with language when I read it at eighteen, and that was followed quickly by Samuel Beckett.

Then there were the perhaps more unexpected, Gertrude Stein and Henry James being two examples. I read everything of James’s I could get my hands on in my late teens and early twenties, and read him entirely differently than any scholars I read on him. I found him pretty humorous in many instances and I loved what I saw as the musical (more like Charles Ives than jazz) elements of his prose, the ways he built sentences and paragraphs with extended riffs that forced you to carry several strands of what seemed like contrary ideas until they came back together to reach a temporary conclusion that would then drive on to another accumulation of phrases into complex sentences and what initially seem like run on paragraphs, only to tie that series up pretty neatly once more and so on.

Stein, of course, as she did for many, introduced the idea of intellect being a source of playfulness and of skill being dependent on that rather than the other way around, if that makes sense.

The last big influences on my early development as a writer and poet were Vladimir Mayakovsky and Frank O’Hara. The latter’s conversational use of The Romantics’ hyperbole and his combining of what was then considered “high” and “low” culture and his willingness to write what seemed like personal, almost epistolary, monologue-poems and then switch to pseudosurreal imagistic lyricism gave me permission to allow more of my “experimental” side to flourish. I had already been hit by Mayakovky’s Cloud in Trousers — an epic poem in length and intent written more as a mixture of lyricism and personal conversation (even if at times declamatory). I saw Mayakovsky’s influence on O’Hara immediately, so was not surprised to discover that he was one of O’Hara’s favorites too.

There are lots more, but that’s probably too much already. (And as for actors, the ones that impacted me the most and whose artistry I studied and felt most satisfied by were Bogie and Cagney, Katherine Hepburn and Spencer Tracy, Marlon Brando and Montgomery Clift, Simone Signoret and Vanessa Redgrave. There’s plenty more whose work I love and admire — Veronica Lake was another early favorite — but those were the main influences on my idea of what acting could achieve, although, as in my writing, my eventual goal was, and is, to express the self-consciousness and self-questioning as well as the self-aggrandizing and yes self-mythologizing that I believe goes on in most if not all humans as well as the usual realistic aspects of being alive and expressing what that’s like in the moment, even if it’s just the thrill of writing something no one else might ever understand or appreciate or see the uniqueness of.

Kimmelman: Yes, what I particularly like about Jerome Sala’s discussion of you is how nuanced he is — taking us, hopefully, closer to the actual in your work. And his quoting of Bakhtin — “there always arises an unrealized surplus of humanness” — says a lot as it sponsors the commentary’s distinctions (e.g., “the self as discovered and the self as made,” “the ‘self’ isn’t so much a particular identity, as the act of trying them [i.e., multiple possible selves] on,” and “Lally’s acknowledgment of the malleability of the ‘self’ is the source, not only of the wit in his work, but the poignancy as well”). These distinctions lead Sala to calling you “the sophisticated (if at times unacknowledged) literary godfather of all sorts of poets” — which maybe takes us back to Marjorie Perloff’s complaint about your deliberately multiformal book Just Let Me Do It — and, was her distrust of the line breaks in this book provoked at heart by a poetics (which I would want to return to in depth later), or if not a poetics then a stance toward writing we might find illuminated in your remark about Kerouac who you insist “did indeed craft his prose and make deliberate choices,” though too many or most people, in your view, see his work as “too unpolished to be comparable to ‘great literature’”?

Kimmelman: Yes, what I particularly like about Jerome Sala’s discussion of you is how nuanced he is — taking us, hopefully, closer to the actual in your work. And his quoting of Bakhtin — “there always arises an unrealized surplus of humanness” — says a lot as it sponsors the commentary’s distinctions (e.g., “the self as discovered and the self as made,” “the ‘self’ isn’t so much a particular identity, as the act of trying them [i.e., multiple possible selves] on,” and “Lally’s acknowledgment of the malleability of the ‘self’ is the source, not only of the wit in his work, but the poignancy as well”). These distinctions lead Sala to calling you “the sophisticated (if at times unacknowledged) literary godfather of all sorts of poets” — which maybe takes us back to Marjorie Perloff’s complaint about your deliberately multiformal book Just Let Me Do It — and, was her distrust of the line breaks in this book provoked at heart by a poetics (which I would want to return to in depth later), or if not a poetics then a stance toward writing we might find illuminated in your remark about Kerouac who you insist “did indeed craft his prose and make deliberate choices,” though too many or most people, in your view, see his work as “too unpolished to be comparable to ‘great literature’”?

But in passing let me quibble with two points made in Sala’s appreciation. One is his accounting for your “humor” (when he discusses your poem “My Life 2,” published in your book It’s Not Nostalgia). He says it “comes from the doubling of self-deflation.” Is this remark meant, in part, as a kind of defense, in your behalf, against a charge of narcissism? If so I think it might be misplaced — insofar as, at least in my reading of your work, one key strength in it is the persona, implied or foregrounded, who seems to exist outside the poem as well as in it; and so, maybe, it would be more accurate to speak of an obsession with selfhood in the Lally poem (but I don’t mean to imply that the work is solipsistic — rather, a persona is in the scene the poem adumbrates but the world is interesting in the scene and the reader sees the persona within this world, the poem’s world). There’s a difference here, surely.

Anyway, my other quibble is more important. I’m coming to feel that the poignancy in your poetry comes not from your “acknowledgement of the malleability of the ‘self’” (as per Sala) so much as from something I think you’ve revealed in what you’ve just said about Saroyan, and it is what I meant to get at, I guess, when I said of the poem of yours I’ve quoted that it was “heartfelt.” You say that Saroyan had “an unshakeable faith.” Maybe it is this that is ultimately compelling in your poem; and maybe this is what I get when I read Williams who, now that I think about it, really did have a faith in the world (a faith that, arguably, was not necessarily shared by his Modernist peers). Does this make sense to you?

There’s another point about self/selves, voice, conversation, etc., which Sala touches upon. And the word conversation is quite germane to it. So, here’s yet another quibble: I think you missed what I actually had in mind when I mentioned Blackburn’s visuality. His poetry reflects the concerns of a speaker who sees the world visually — yes, of course his language was arranged on the page in startling, groundbreaking ways that were decidedly spatial. But what I meant was that Blackburn existed on the visual plane, in a spatial dimension (thus, while his language showed a concern for sound, what he was really interested in was how the world looked and how people’s relationships were, perhaps determined by, but in any case capable of, being understood or savored in visual terms). You, on the other hand, are concerned with matters on the temporal plane. And this leads to a sort of musically contained poem. Of course your music is understated as it fits into your efforts to make your poems look a bit unkempt, à la Kerouac, or otherwise look and sound talky, even when they have been carefully wrought.

Now, is this not emblematic of what good conversation is like, a bit rambling but incisive too?

I think it is no accident that you pay homage to, among your contemporaries or near-contemporaries, di Prima, Bremser and Kauffman. Who can be surprised at this, after what you have said about the musicians who have played an important role in your life, in influencing your writing? Kauffman confirms the truth and beauty of jazz for you, what you came to intuit when still quite young, a kid. As for Bremser, I remember fondly a reading of his many years ago; it was like scat singing except he was speaking, in actual words, but it was pure music, really.

As for di Prima — you mention Thirteen Nightmares; I believe that became part of her volume titled Dinners and Nightmares, and that volume contained what I think was her first chapbook publication, This Kind of Bird Flies Backward, an astonishingly fresh and beautiful collection (including the undeniable series of poems she titled “Poems for Brett” and “Songs For Babio”). The economy of language in her work then was amazing, and the poems (songs?) had a supple, sinewy lyricality and syncopation to them. And what was her language like? It was hipster-spoken, jazz-inflected, inner, intimate thoughts, intimate thoughts brought into the social realm. I like what Sala says when he speaks of what is finally to be found in your poems: sheer “attitude.” di Prima had that in those tender and tough, jazzy early poems. I guess that chapbook came out at about the same time that she was editing Floating Bear with Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones). No I don’t think that she consciously had the music or personality of Charlie “Bird” Parker in mind when she titled that chapbook, but she was on the scene — no?

And like Sala also says about you: your “powerful style, mixing talk, a jazzy rhythm and pre-hip-hop improvisatory rhyme with pure attitude, seemed predictive, in retrospect, of the performance styles to come after [your] own work began.” I’m reminded here of a poem by Michael Stephens (who has a similar background to your own — Irish-American, blue-collar Brooklyn and later Long Island), written at the time he and I went to hear di Prima, young and redolent, read her work at St. Mark’s Church (about 1966). She read beautifully, and then apologized for having to leave abruptly, since she had four unattended kids at home waiting for her. Remembering that evening, I am struck by the parallel — you deciding not to stop being a struggling artist because you were raising two children by yourself. What were those days like for you?

Anyway, Stephens’s piece was called “Tough Kid with a Poem” and it was jazzy in its talk. You may remember that you and he (and I) had breakfast together a few years ago (when he was in the States from London briefly, where he’s been living these days). You two talked about Hubert Selby, Jr., the author of the amazing novel Last Exit to Brooklyn (eventually made into what I think was a fine film), set in what was then a very tough Red Hook, Brooklyn, and I wonder if you would agree that at heart that book is jazzy, not least of all as regards the rhythms of its narration. Of course you and Stephens were both friends with “Cubby” (one of my regrets was that I never met him). And my sense is that he was important for both of you, your respective writing.

Left to right: poet/filmmaker Joel Lipman, actor/poet MIchael Harris, Hubert Selby, Jr., Lally, and Eve Brandstein, circa 1988.

I guess this observation allows me to ask if your musical and poetic forbears inform your prose too, not just the work that may be multi- or cross-generic, but that which one clearly assumes is prose. Is there musical talk in your prose too, in your view, an understatedly musical talk? Or do you perhaps not accept my description of your work as I’ve explained it here? And do you see your music, and for that matter jazz, as inextricably involved in what I’ll call your “tough” upbringing? di Prima too had a Catholic blue collar Brooklyn childhood (if memory serves me right). I won’t comment on Etheridge Knight’s background, or Bremser’s or Kauffman’s, though I think this is relevant to what I’m saying. I don’t know how to describe the politics here (thinking of what the sixties feminists said of how “the personal is political”), but maybe there is a socioeconomic dynamic in play.

One more thing: Is the musical a way to maintain faith in the world?

Lally: It occurs to me when you add at the end your last question — “One more thing: Is the musical a way to maintain faith in the world?” — that my answer is: the musical is a way to maintain faith in the word! (as well as “the world”). My earliest influences were all music or related to music, as I pointed out previously. But while I mostly mentioned lyricists, it was also instrumentalists. I played piano from as early as I can remember (and added other instruments later, trumpet, sax, bass, etc.), starting lessons at four. I quit for a while in my early teens out of rebelliousness, mostly toward the formal lessons kind of learning, but picked piano back up again in my late teens and played a little professionally through my mid-twenties, when I quit again because I felt I needed to focus on my writing, particularly my poetry, and that dealing with other musicians, and club owners and managers, and lining up gigs etc. was all taking away from my already busy life at the time (I was attending the University of Iowa Writers Workshop on the G.I. Bill and working on a BA and MFA at the same time — first time the school let anyone do that, I was told — as well as working a few part-time jobs to supplement the help from the G.I. Bill and support my growing family (we had our first child while there and our second shortly after leaving). So I gave up playing music to concentrate what energy I had left on my writing.

But my writing had always been informed by music, including the verbal kind I found in my neighborhood, which began with the “toasting” I learned from African-American friends, a proto-rap form of boastful rhyming similar to “the dozens” which I also learned from Irish-American friends who had their own versions of rhyming couplet put downs etc. as well as from the story telling and joke telling of my Irish relatives. There was a rhythm and melody to these verbal expressions that delighted me as a kid and that I always wanted to capture for “the record” as I saw part of my goal as an “artist” being right from the beginning.

And that fits into your quibble about Paul Blackburn’s work, which I think you’re right about. His was more a spatial component and mine temporal, as you say, especially in the musical sense, i.e. rhythm. Early on, my work was often taken as having been written by a “black” poet as opposed to a “white” one, and I think that had a lot to do with the rhythm, as well as subject matter. I was even invited to an awards ceremony in DC around 1969 when I moved there from Iowa City with my family to take a teaching gig (the only one I ever had, for four years, matriculating along with the other students as it were). I showed up at a cocktail pre-awards party for the nominees for the prize and startled my hostess and those who were giving the award because they had assumed I was “Negro” as they stutteringly explained that the award was not meant to be given to a “white” poet, so it was given to someone else who fit their category.

Around that time I was affected by an experience teaching Frank O’Hara’s poetry that opened my heart in a way it hadn’t been before to not just the artistry of O’Hara’s work — which I’d always been drawn to but also had a lot of arguments with (mostly because I found his urbane wit and eclectic but often rarified references “elitist” and probably felt threatened in some ways by that) — but also to his humanity. I literally “fell in love” with him through poems I’d been very familiar with but saw in new ways when explaining why they were great to a classroom full of undergraduate women; the poems were “The Day Lady Died,” “A Step Away from Them” and “Steps.”

I had always loved O’Hara’s ability to approach a poem from whatever angel (I meant “angle” but maybe “angel” is truer to reality) aroused his interest and inspired him at the moment, from conversational to formal to “experimental” (so many of his poems predict the whole “Language” movement in my perspective) but I felt almost like the anti-O’Hara up until that moment, arguing from my side that putting French terms and obscure poets’ and artists’ names in poems was somehow condescending to the kid I had been and the people and place I came from and knew. But that day in the classroom, in breaking down the elements in those three poems that made them “work,” I actually teared up, not just from the sentiment (and sentimental) perspective of “love” and “art” (whether or not, in the terms of those days, “high” or “low”), making it possible to transcend “life” (i.e. setbacks, struggles, disappointments, failures and ultimately loss and death), and choked up, surprising my students and myself. I went home that evening and reread all the O’Hara I owned at the time, which was every book of his published up to that point, and had this epiphany realizing, at least for myself, that what I had taken as “elitism” was actually a “modern” extension and reimagined expression of the kind of universal democratic inclusiveness I so admired and identified with in Whitman’s work since I was in my teens.

I later articulated this perception of O’Hara’s work in a long poem called “In The Mood” (a half decade later, 1977) in response to a critic’s misreading of O’Hara’s influence on me (a lot of people saw that influence after that O’Hara epiphany, and at least one interpreted my experimenting with bisexuality in the early seventies as a direct result of it, and there’s a lot to that). It wasn’t long after that O’Hara epiphany that I read in a series at the Smithsonian that included John Ashbery as well, and I had a change of heart about his work too. I had seen his poetry up to that moment as brilliantly original in terms of structure and language juxtapositions (Ted Berrigan had passed on his famous dictum to me only a few years before: “No ideas but in juxtapositions”) but too cold and calculated(!) for my taste. But at the Smithsonian reading, Ashbery read that Popeye sestina “Farm Implements and Rutabagas in a Landscape” and it being the first time I’d heard him read, I suddenly got the rhythmic use of language and the juxtaposition of poetic strategies that allowed him to get away with the line about Popeye scratching his balls, in front of all these well dressed and well behaved Smithsonian/DC matrons and patrons and I cracked up, actually had to keep myself from falling to the floor laughing, which I could see Ashbery appreciate, though his nasal monotone didn’t alter an iota. Later he came up to me to introduce himself, which was pretty gracious of him, and we became friends.

Some in the “Black Arts” movement who had considered me one of them, in whatever ways a “white” poet could be, were disappointed by my new appreciation for “The New York School” poets, or what they saw as their influence on me — even though I’d been reading and digging, on some level, my usual autodidact eclectic mix of poetry since my teens. And when I began writing out of the sexual experimenting that I indulged in during that period (the early seventies) I ended up getting criticized or just dropped. And more of that followed me after I moved to Manhattan at the start of 1975 and it eventually became clear that I was really a pretty “straight” “white” “male” poet, at a time when all three categories were becoming suspect unless coupled with a clearly Marxist and/or “Language” (as it began to develop among many of my fellow poets and friends in the late seventies) and/or “punk” stance (but only according to a certain elitist, as I again saw it, group who seemed to dismiss or else bristle at my self-identifying as a “punk poet” for years before the term even became current — I used it e.g. in that long autobiographical 1974 poem “My Life” that had an impact on some younger poets at the time, some contemporaries too). Having been a political activist for most of my life, not just a theorist, and having used many approaches to “the poem,” including ones that would later be seen as “language-centered” and still carrying with me, in my heart and in my writing, including the prose, those musical influences of my youth (including the rhythms and language of di Prima, Bremser and Kaufman), and now having also incorporated some of the strategies of “The New York School” — I absorbed all that into the same goal of trying to get as close to “the truth” of my reality as I could without over-sentimentalizing it, but also without scrubbing all sentiment from it, if you see what I mean. But I think in many ways it all just became too much of a complicated mix for some who like to be able to categorize and/or identify with a clear and simple message or approach or technique or stance etc. and I was just confusing them too much, or letting their agenda for me down. When that became clear to me, I moved on once more, this time to Hollywood to explore another arena that had influenced me hugely as a kid and that I always wanted to experience from the inside.

I think I got away from your questions, but that’s my response anyway.

Kimmelman: So, showing up in Los Angeles, how did you get comfortable in the poetry world there eventually, a New Jersey/New York transplant who eventually gets published by a press like Black Sparrow? And when you finally returned to the East Coast, did you merge easily into the stream, pick up the heartbeat, of the poetry being written and read there?

“No ideas but in juxtapositions”! I love what I take to be Berrigan’s insouciance and filial irreverence in echoing, of course, Williams’s “no ideas but in things.” Do we see here a link in your mind between O’Hara (and I’ll throw in Berrigan) and the “language-centered” writers who emerged about when you were composing your poem “In the Mood” (I would think this case would be easier to make if you were to cite Ashbery or someone like Clark Coolidge as forerunners of the Language folk, whereas I see Berrigan as finally more in sync with a contemporary like Bernadette Mayer)?

Anyway, let’s talk about “In the Mood.”

I would not be surprised to learn from you that to understand what your return east was like, and to get more insight into your move west, we ought to discuss this informative poem. So allow me to make some observations about it and, what I think is appropriate, some observations about the three poems by O’Hara you’ve mentioned — who figures centrally in your poem — which you cite as being really important to you in your life and I presume to “In the Mood.” Your poem is both an ars poetica and what I’ll call an ars biographia (in my saying this please don’t feel like we have to loop back to what we’ve said about your, let’s call it, poetics of the self — except maybe to touch on it as it connects with O’Hara’s work).

The first similarity that jumps out at me is that both O’Hara’s work and yours are talky. Once again the music of the speaking voice — in conversation, in dramatic monologue, in intimate inner thought, or whatever — is a key to both poetries, it seems to me. And your poem might be written out as prose but your line breaks, once the reader gets past the setup opening line, the enjambments, are striking:

It was in 1964 that I first read Frank O’Hara.

The book was Lunch Poems and it was sitting on

the kitchen table of the first intellectual I

was friends with. He was a graduate student in

a state college in Cheney, Washington, and I

was an Airman Basic (lowest rank due to court

martial) stationed at Fairchild Air Force Base

outside Spokane, Washington. The first poem

I read in the book was “The Day Lady Died” [etc.].

Actually, I hear a bit of the talk-chant of the opening of Howl here, but I guess we could start to find a lot of poems written at the time (maybe by someone like Joel Oppenheimer) that strive for this aesthetic. Still, it’s interesting what you do with the speaking voice here, your own singular creation. The line breaks provide a tautness in your narrative, and then the reader starts to get a rhythm to the story the poem is telling, and yes in a way to the persona, speaking in the first person — and the way your poem begins, the “I” prominent in the way O’Hara’s is, within a dynamic of a larger setting though, so you seem to be wanting to echo or reprise O’Hara’s voice and concerns. Here, for comparison, are some gorgeous lines from O’Hara’s “A Step Away from Them” (one of the three poems you said were seminal):

A blonde chorus girl clicks: he

smiles and rubs his chin. Everything

suddenly honks: it is 12:40 of

a Thursday.

The cityscape here, the poet as looker, arguably, are captured in what seems impromptu, casual, unworked, full-of-loose-ends verse (not unlike Kerouac?).

I love the way your poem goes on and on — also, perhaps, O’Haraesque, in that sense. And I love this truly insightful, and pissed-off, passage of yours, your paean to O’Hara (also, I must add in passing, this is a nice example of the importance of the breath, as Olson laid down in his ars poetica “Projective Verse”):

[…] one day I realized how much of what I was

reading and often admiring going on around me

in the poetry world was a kind of picking of

scabs and flashing the open sores and wounds

as badges and credentials and how O’Hara

totally sidestepped that contemporary tendency

by tone and choice of vocabulary that cut

through the hopelessness of so much poetry

and replaced it with the joy of writing the

poem. What a simple but wonderful revelation.

The joy of writing it down — that was

what it suddenly seemed to be about in

a way that made me think of all I had heard

the painters of his time were trying to do,

get across the action of the creating

rather than the product that was so finished

it showed no signs of the activity, the energy

and spirit of the actual work that went into it.

O’Hara’s poems were little excursions into

the act of writing poems with the kind of

mindset that keeps us trying sex with strangers

again and again, the hope that this time

is gonna be great, give us much pleasure

and satisfy a lot of frustration and totally

annul the boring horrible deadening, killing

in fact, effects of living.

Yet, unlike in the typical O’Hara poem, your poem has the sense that the speaker is really heading somewhere with what he’s talking about. Would you agree? But maybe the diatribe is there in his poems, if we look for it?

Also in this passage I love how you get a doubling effect, a kind of poem within a poem. Are we seeing you working here in a cross-generic way, writing both a poem and an essay, and not just biographical but also literary-critical, an essay-poem (was this new in the later seventies, preceding the Language people’s work, for example Charles Bernstein’s Artifice of Absorption? — in any case I can see it leading to the recent genre-transgressing of someone like Eileen Tabios, Stephen Paul Miller, or perhaps Kristin Prevallet).

The sense of talk in O’Hara’s poems — intimate talk, and casual, though a lot is hanging on it, possibly everything — is wonderful, and I often get that in your poems too. Now, there’s something else I find that is curious. Of the three O’Hara poems you have pointed out, two are elegies, and arguably the third, “Steps,” contains certain elements that might allow us to group it with the other two as being elegiac (for instance when the O’Hara persona asks, “where’s Lana Turner / she’s out eating / and Garbo’s backstage at the Met / everyone’s taking their coat off / so they can show a rib-cage to the rib-watchers”). Maybe even when the poem was first written these lines were, if not elegiac then at least nostalgic. Yet is there not an essentially elegiac strain in all of O’Hara’s work, I would say, a memorializing that invites nostalgia though that sidesteps sentimentalism. Do you agree? And would you say the same for some of your work (I recall, fondly, your very moving albeit quiet prose account of visiting your aging brother in Japan, whom you’ve mentioned earlier, a probing tribute), and might you say this is true particularly for “In the Mood”? We are asked to, and we do, live in the moment in an O’Hara poem. And do we not sense the ephemerality of the world and become, thereby, urgent about living in it while we can? Is that also some of what your poem is meant to do?

Are you being elegiacal, deep down (or merely wanting to invoke the idea of the elegiacal), when you write this: “[…] suddenly I caught myself / starting to cry and I never cried back then, / in fact except for a short interlude of about / a year of weepiness I never cry period, except / over old movies and musicals and it was that / heartstring O’Hara had suddenly plucked in me / through his poetry that sang so naturally [etc.].” Or maybe this passage is not really elegiacal but rather is just sincere and direct, and moving for that. But I do sense, in any case, that in this poem, and in other poems of yours, you are interested in being — as happens in an O’Hara poem — very much in the present, the vibrant now.

What I sense you want in your poems is what O’Hara is in fact espousing when his persona in “Steps” opines, having mentioned the Pittsburgh Pirates who had been winning baseball games of late, that “[…] in a sense we’re all winning / we’re alive[.]” O’Hara’s speaker lives in the moment, indeed in the exhilaration of it. Here’s how this poem daringly ends, its final stanza:

oh god it’s wonderful

to get out of bed

and drink too much coffee

and smoke too many cigarettes

and love you so much[.]

The final line is so fleeting. The line is also sincere and heartfelt — getting back to the poem of yours I quoted earlier. And this is true of “In the Mood” where you speak of O’Hara’s “generosity and non-exclusiveness” that you then say “is rare.” You also remark, further on, that “sincerity / is supposed to be too costly,” and you deftly speak of

conversational concessions

about the glory of life despite the futility of

“survival.”

Okay, so, can we think of this set of lines as being the hallmark of your work?

Lally: What it was like to move to Los Angeles (with my second wife who I’d just married and my two kids from my first marriage I’d been raising on my own up ’til then in Manhattan) and into an entirely new set of scenes, the local poetry scene(s), the Hollywood scene, the whole West Coast Southern California bunch of scenes (surfing, health food, car culture, etc.). It was difficult.

There were very few readings going on in LA in 1982 when I arrived. I knew something about the Venice Beach Beat scene from the fifties and beyond (and eventually became friends with some of the originals, like Frank T. Rios, a displaced New Yorker since the fifties I think and street poet — and “the man in black” before a lot of others who held that mantle) and Beyond Baroque, where I gave one of my first readings in LA and knew Dennis Cooper (who published the magazine Little Caesar and under that logo a collection of my poetry the year I moved to LA called Hollywood Magic) and Jack Skelley (who published the poetry magazine Barney).

There were very few readings going on in LA in 1982 when I arrived. I knew something about the Venice Beach Beat scene from the fifties and beyond (and eventually became friends with some of the originals, like Frank T. Rios, a displaced New Yorker since the fifties I think and street poet — and “the man in black” before a lot of others who held that mantle) and Beyond Baroque, where I gave one of my first readings in LA and knew Dennis Cooper (who published the magazine Little Caesar and under that logo a collection of my poetry the year I moved to LA called Hollywood Magic) and Jack Skelley (who published the poetry magazine Barney).

My second wife, Penelope Milford, had some cachet in Hollywood. She’d been nominated for an Oscar a few years before, so we were instantly a part of that scene, and the publication party for Hollywood Magic included a lot of friends and acquaintances who happened to be movie actors, or “stars” in some cases, as well as others in the film and music “biz” (I had starred in a couple of horrible horror movies in New York before moving and got some attention). So there was some sniping and carping about my “going Hollywood” (even some criticism to that effect in some poetry newsletters and rags) even from former fans of my work as I discovered when a new Hollywood friend, a comedian at the time and later a filmmaker, told me about a visit he made to a bookstore in Detroit where they had several of my books, and even a picture of me on the wall, and when he took down one of my books from the shelf a young man asked him if he was a fan of my work and my new friend said he hadn’t read any of my books yet, then asked if the young man was a fan, and he said, “I used to be, before he sold out to Hollywood.”

My actual first poetry reading in LA was in West Hollywood at an independent bookstore called George Sand. A friend of Penny’s was a producer on Entertainment Tonight and a fan of my poetry, so she came with a crew to cover it but ended up being called away for some “breaking show biz news” before the reading happened. Yet just hearing of their presence pissed off some poets and poetry fans who weren’t even there, though the bookstore sold out every copy of the seven titles of mine they had special ordered extra copies of for the readings. (I read with Lewis MacAdams, who I’d first met through Ted Berrigan in the sixties because Ted thought our poetry had some things in common, though Lewis didn’t agree).

After the reading a diminutive Frenchman who owned an outdoor avant-garde theater in Hollywood came up to me with effusive praise and asked if I would create a show for his theater out of the book I’d been reading from, Hollywood Magic. Which I did, using a jazz musician friend, Buddy Arnold, and two thirds of a juggling/magic new wave vaudeville act, The Mums — Albie Selznick and Nathan Stein — and my wife and another actor/writer, Winston Jones.

The words of the show all came from poems from Hollywood Magic, but the scenes came from my movie memories and personal life. There was lots of extreme language and imagery which got the show moved to an indoor theater in Santa Monica after the Frenchman got nervous about his neighbors because my poetry not only used a lot of profanity and got pretty sexually graphic, but also included a lot of street language, like the n-word among other offensive terms, and he began to get threats and since the theater was outdoors wanted me to cut a lot of the offensive language which I wouldn’t do, so we moved to The Odyssey where a Wallace Shawn play was running and were given the time slot after it and I incorporated the stage set from Shawn’s show covered with white tarps into mine, like having magician Albie Selznick cut his way out of one of the tarps each night with a switch blade etc. or my wife appear beneath a tarp I slowly removed revealing her lying on a bed in skimpy lingerie while the two Mums juggled dildos over the bed and my wife, ending with them catching the dildos aiming in the right direction between their thighs.

All this activity led to some local media attention that seemed to draw the ire of some local poets who had been there long before I arrived and maybe hadn’t gotten as much attention. By 1986 my marriage had failed and acting jobs had dwindled in part because of my refusal to be tactful and act in my own best interest, or what I saw as standing up for my rights as a creator and not playing the Hollywood “game” etc. (I had work for a few years as a scriptwriter and “doctor” but also had to take gigs driving a limo and as a night guard in a hospital etc.). But I organized several benefits for various causes at which I had poets as well as movie and music stars read poetry, so was asked to start a weekly poetry reading series in a club in East LA, called Helena’s, by Helena, the part owner, an ex-belly dancer friend of Jack Nicholson’s — she played the angry dyke in the back seat of the car in Five Easy Pieces — who introduced me to another ex-New Yorker, Eve Brandstein, a poet/scriptwriter, who became my partner in the venture we eventually called “Poetry in Motion.”

The format I’d come up with decades before for poetry benefits as well as weekly series I’ve run is to have a lot of poets read briefly, a mix of styles and approaches, giving an audience the chance to find something they dig that hopefully will turn them on to poetry if they weren’t turned on to it before. I wasn’t aiming for poetry fans, but for a more general audience who might not realize how many kinds of poetry there are, including ones that might inspire or at least engage them.

For Helena’s, we let people we knew from the movie and TV and music communities in LA read poetry if they’d written it themselves and it was good enough. Sometimes I’d help some folks edit their work or do some rewriting, something I’d done both for friends and professionally over the years. But because some of these people were well known — even considered “celebrities” — some local poets I’d ask to read in the series turned me down, objecting to the venue (a hangout for the sort of alt-Hollywood crowd, like Nicholson, or later a club called Largo where we moved when Helena’s closed and Largo opened and the owner wanted the crowds and the attention we got), saying it was too upscale or “Hollywood” or not wanting to share the podium with people they considered not “real” poets, which just made me push that aspect even more, seeing another form of prejudice I hadn’t realized existed, against actors in general and “stars” in particular as beneath the cultural credential requirements of the poetry scene (this was before actors like Viggo Mortensen and James Franco et al. became accepted as poets and performance artists as well as movie stars).

But it was still so successful, standing room only crowds lined up at the door to get in and all kinds of local and national and even international media came to cover it. Unfortunately a lot of the coverage was snide, for which the reporters who covered us would apologize, saying they ended up being won over by the poetry, being moved or enlightened or entertained etc. by the work but their editors would insist on the “celebrity” angle and get nasty, as in one article about it in, I think Newsweek, that had the headline “Whitman Wannabes” (highlighting the “brat pack” connection because one of the poets, and a good one, was Ally Sheedy), and a bit in The New Yorker’s Talk of the Town section that singled me out as a “Hollywood poet hustler,” as I remember it.