Recasting poetry

'The long biography of a poem'

Kaia Sand

In Distant Reading, Peter Middleton describes reading a poem as though it has a “long biography.” This approach involves “mining what is available of the aggregative textual archive that composes the textual memory of the poem, its showing in magazines, performance, anthologies, its construal in reviews and commentaries and other treatments” (23).

Consider the long life of Claude McKay’s "If We Must Die." Written in 1919 when Claude McKay was waiting tables on a railroad dining car, this poem rallies courage and dignity as resistence to oppression.  The poem “exploded out of [him],” according to McKay, in the context of racial and economic tensions he witnessed from city to city. He first read it to his crewmembers on the train who he describes as responding with emotion, one waiter crying. The poem was published by the Liberator in 1919, “above an article on Bolshevism and religion,” according to William Maxwell, and reprinted in dozens of African American publications soon after. Fast forward to the 1930s, and a divergent context: Winston Churchill may or may not have read it to the House of Commons (Al Filreis explores this scenario here), rallying the country to war—"If We Must Die" recast as a war poem. Fast forward again to 1971, and the prison uprisings in the Attica Prison: In 1971, Time magazine described how a poem found on a prisoner was “crude but touching for its would-be heroic style,” mistakenly attributing authorship a prisoner, and adopting a conscending tone in the process. A month later, Gwendolyn Brooks chastised Time Magazine with a letter to the editor (“Please tell the poetry specialist who gave us the above that his “find” is a portion of one of the most famous poems ever written ...”) These are some marquee moments in the long biography of “If We Must Die” that inform my reception of the poem. I also read the poem through more private memories—projecting it in front of a winter classroom in western Oregon, or recently stumbling on tens and tens of tribute YouTube videos.

The poem “exploded out of [him],” according to McKay, in the context of racial and economic tensions he witnessed from city to city. He first read it to his crewmembers on the train who he describes as responding with emotion, one waiter crying. The poem was published by the Liberator in 1919, “above an article on Bolshevism and religion,” according to William Maxwell, and reprinted in dozens of African American publications soon after. Fast forward to the 1930s, and a divergent context: Winston Churchill may or may not have read it to the House of Commons (Al Filreis explores this scenario here), rallying the country to war—"If We Must Die" recast as a war poem. Fast forward again to 1971, and the prison uprisings in the Attica Prison: In 1971, Time magazine described how a poem found on a prisoner was “crude but touching for its would-be heroic style,” mistakenly attributing authorship a prisoner, and adopting a conscending tone in the process. A month later, Gwendolyn Brooks chastised Time Magazine with a letter to the editor (“Please tell the poetry specialist who gave us the above that his “find” is a portion of one of the most famous poems ever written ...”) These are some marquee moments in the long biography of “If We Must Die” that inform my reception of the poem. I also read the poem through more private memories—projecting it in front of a winter classroom in western Oregon, or recently stumbling on tens and tens of tribute YouTube videos.

While this example emphasizes reading an intact poem through swerving contexts, I am interested in how Peter Middleton's idea of the long biography of a poem might be claimed by the poet herself. How might a poet take an active role in recasting work? How do changing audiences and contexts imbue the poem with significance, and how the poem might bend, alter, accrue these contexts, too?

A poet might choose to recast a poem when it moves from functioning like the news to a no-longer-immediate context. Bill Moyers recently described on The Daily Show how the media often dwells on the “immediate,” while as an investigative journalist, he mines for “the important.” Both are compelling vantage points for poetry. While an immediate focus often equals a superficial one on the mainstream media, poetry that functions like news often does so with a critical edge. Poetry unveiled as urgent and critical news can certainly charge a poetry reading (I'll write about Aaron Vidaver's “The Worst is Behind Us,” which critiqued the early media coverage of the financial meldown and subsequent economic hardships, in a future commentary.)

An interesting example comes from a February 28, 2003 Social Mark reading in Philadelphia. At a Slought Foundation group reading, Kristin Prevallet performed “From Cruelty to Conquest,” applying an Oulipian technique to a speech George Bush gave before the United Nations as he mobilized U.S. troops for war in Iraq. She blocked out words with “oil” until the speech was overtaken with oil. Later that night, in what Ron Silliman described as “a strange apotheosis,” Jules Boykoff chose the same Bush speech to perform a different procedure. He removed text from the speech, revealing rhetorical emphasis on such moments as “We have no quarrel with the Iraqi people.” Boykoff ended his reading with the comment that he had “just removed some words that [he] thought were superfluous.” (Both poems are archived at Slought Foundation. Prevallet's poem is at the 56:30 minute marker; Boykoff's is at 1:21:49). Poetry as critical journalism.

When poetry functions like news, what happens when it is no longer immediate? How might a poet recast the work for enduring importance beyond archival interest?

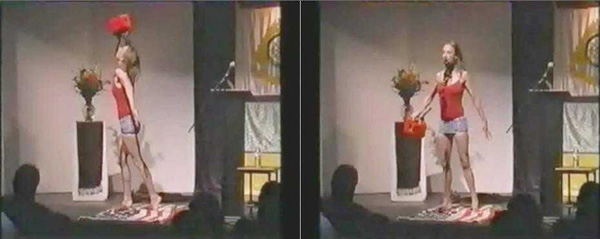

A year and a half later, after her poem ceased to function like news, Prevallet recast it into a performance at Naropa University where, decked in a bathing suit, she guzzled oil (actually molasses), choking on it as she also choked the on the word “oil.” While her first iteration of the poem was timely—the United States was less than a month away from launching war on Iraq—her later performance interrogated the enduring, violent role of oil in maintaining an USAmerican 'way of life.'

Kristin Prevallet performing “From Cruelty to Conquest” at Naropa University, July 2004

Prevallet has experimented with recasting in other ways. She resisted her “inclination to write new poems just because [she was] bored with reading” her book, I, Afterlife: Essay in Mourning Time by recasting the elegiac work from a focus on personal loss to shared grief, “public mourning.” (Read her description in an issue of Big Bridge edited by Dale Smith. Prevallet's essay is catalogued in the section, “Gallery 1: Looking Around”).

By recasting poetry one views it as “probably unfinished” as Middeton writes (24) “The density of social spaces within a specific geography has also increased enormously, producing social distances that contemporary literary texts have to weather somehow, treating them either as local distances of climate aginst which the text must be proof, a background noise to be ignored, or a field of difference to be celebrated and incorporated into textual production” (3). Recasting a poem is a way of embracing that “field of difference“ to consider how the poem might be charged anew.

I have been thinking through these possibilities in my poetic practice, experimenting with recasting poetry through my project, Remember to Wave. Because I am interested in inexpert inquiry (something I'll explore in a future commentary), I wanted to leave the inquiry open to change. Composed and performed as a walk, Remember to Wave evolved in part because of how other people participated. But I also became interested in recasting the work off-site, both through creating a book and various maps and through reading variations of the work in various contexts, whether a few miles from the walk in a neighborhood bookstore or thousands of miles away. Each iteration contributes to “the long biography of the poem” and helps me sustain attention.

There's a whole lot of language out there. A mess of it, actually. Producing poems rapid-fire heaps more language onto that mess, as we busy ourselves with it all. Yet, poetic form is a way of gathering the mess into significance. By staying with a poem, rethinking it, recasting it, one might create a dynamic, sustained form for gathering the mess.

Moxie politik