Paradoxical print publishers TRAUMAWIEN

Since the advent of the internet, advocates and critics alike have heralded the end of the book. And yet, despite the worst efforts of the publishing industry, not only has the book persisted, it has proven to be a particularly elastic form, adept at adapting to remarkable changes in the way we read, write and interpolate narrative.

For centuries the printed book operated as a closed system, invested in concealing the structural processes of writing from the reader. In his now infamous 1992 New York Times article, "The End of Books," Robert Coover observed, “much of the novel's alleged power is embedded in the line, that compulsory author-directed movement from the beginning of a sentence to its period, from the top of the page to the bottom, from the first page to the last.” And yet, as Vannevar Bush astutely commented nearly 50 years earlier in "As We May Think," published in the July 1945 issue of The Atlantic, "the human mind does not work that way. It operates by association. With one item in its grasp, it snaps instantly to the next … in accordance with some intricate web of trails carried by the cells of the brain." George P. Landow suggested, in his massively influential book Hyper/Text/Theory [1994], "the very idea of hypertextuality seems to have taken form at approximately the same time that poststructuralistm developed… both grow out of a dissatisfaction with the related phenomena of the printed book and hierarchical thought." For three decades Derrida insisted that, “only in the book … could we indefinitely designate the writing beyond the book.” By the time of his last book Paper Machine [2005] Derrida was writing of the World Wide Web as the ubiquitous book finally reconstituted, as "electronic writing, traveling at top speed from one spot on the globe to another, and linking together, beyond frontiers."

Consider, then, the paradoxical position of Vienna-based publishers TRAUMAWIEN.

The vast majority of the text produced by computer systems – protocols, listings, listings, logs, algorithms, binary codes – is never seen or read by humans. This text is nonetheless internal to our daily thoughts and actions. As such, TRAUMAWIEN considers these new structures to be literary. TRAUMAWIEN editor Luc Gross describes this literature as “a system of virtualization in imagination, always describing breaking points in our perception of world.” Gross goes on to say, “Our range not only includes networked texts, algorithmic texts, interfictions, chatlogs, codeworks, software art and visual mashup prose."

Contrary to Derrida’s assertion that "the book is both the apparatus and the expiration date that makes us have to cut off the computer process," TRAUMAWIEN conceive of the print books they publish as narrative snapshots of computer generated literary processes which would otherwise already disappearing as soon as they are written.

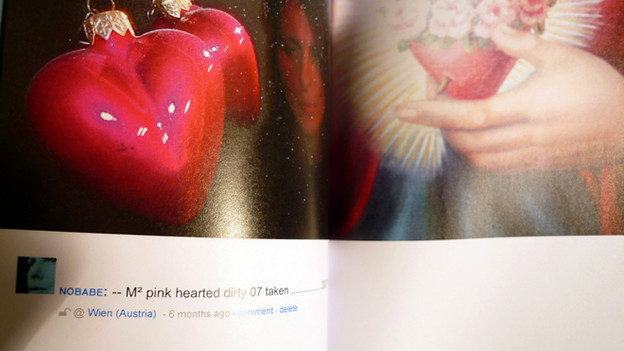

TRAUMAWIEN launches each new round of books with a night of performances intended to challenge the digital as the sole locus of these born-digital texts. For example, during the first launch event, excerpts from Shocking Blue Demon Lover – “a real-time, web-written, literary, visual, dada mashup micro prose project… bilingual fictional digital fluxus poetry love story, role-played by the photographer, writer, filmmaker and journalist Margit Hinke (aka @nobabe) – were read aloud by a stuntman, in the form of Zurich/Basel-based Shakespearean stage actor.

For more information about TRAUMAWIEN visit their website and/or their facebook page.

All TRAUMAWIEN books are available on Amazon.com

Performing digital texts in European contexts