On Weiner, Acconci, Perreault, and Graham

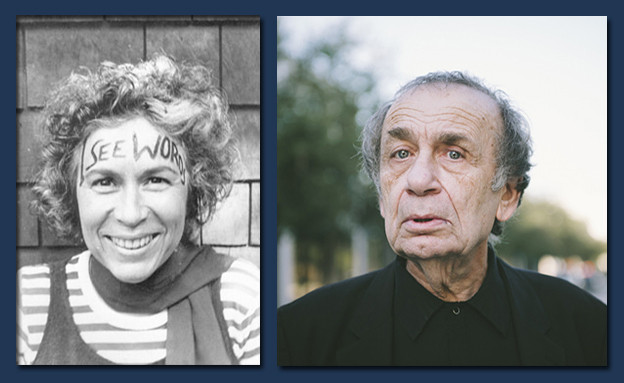

Before she matriculated to clairvoyant grande dame of the Language poets, Hannah Weiner was a Conceptual writer, performance artist, and lingerie designer on the Lower East Side. In light of Divya Victor’s call for this forum, I want to briefly address her Conceptualism. The tricky part is that little record of her early activity has survived. Her collaborator John Perreault reports that she set fire to the documentation of her Street Works and performance projects of the 1960s. Only since Patrick Durgin’s edition of Hannah Weiner’s Open House (Kenning Editions, 2006) has a recovery of her uncollected work begun in earnest — a project that he continues here and here. The mimeo zines of the era hold even more surprises in store, and below I highlight a few wayward works that firmly plant Weiner in the field of 1960s Conceptualism. These works, moreover, demonstrate that Weiner was constructing a pluralized, even polyvocal Conceptualism in contrast to a certain isolationist tendency among her peers.

Hannah Weiner’s initiation in the poetry world of New York began with writing courses taught by Kenneth Koch at the New School in 1964 and 1965. Within a few short years, she was participating in the community that was centered around art venues like the Dwan Gallery and Grain Ground gallery and magazines like 0 to 9, The World, Chelsea Review, Dial-a-Poem, and Big Deal. Two magazines that are especially vital for Weiner’s Conceptualism are 0 to 9, edited by Vito Acconci and Bernadette Mayer, and The World,edited by Anne Waldman. In these pages the artist and poet contributors marshal language in ways that closely intersect and align with one another, as can be seen by juxtaposing a few examples. Take Acconci’s untitled poem in The World 11 (April 1968):

On the one hand there is a finger.

On the one hand there is another finger.

On the one hand there is another finger.

On the one hand there is another finger.

On the one hand there is another finger.[1]

A graduate of the Iowa Writer’s Workshop, Acconci is often contrasted with the confessionalists who were his teachers and who then dominated the publishing houses. Rather than explore psychological interiority, as did Robert Lowell or Anne Sexton, Acconci is the bad boy who whittles self-presentation down to a metonymic series of cool, unadorned notations. Acconci is in no rush and never in a tizzy. The poem is a case study in what Georg Simmel calls the blasé mentality that guards against sensory bombardment in the modern metropolis.

A similar gesture operates in work by poet and art critic John Perreault. See his “Measurements,” which appears in the same issue of The World:

from head to toe. ................................................. 5 feet 10 inches

circumference of head ......................................... 34 inches

nose length ............................................................. 2 1/2 inches

distance between eyes............................................ 1 1/2 inches

width of mouth ..................................................... 3 inches

circumference of neck ......................................... 14 1/2 inches

from shoulder to shoulder .................................. 19 inches

from shoulder to elbow ....................................... 11 inches

from elbow to wrist ............................................. 12 inches

circumference of upper arm ................................ 11 inches[2]

Or take the artist Dan Graham. Although never published in 0 to 9 or The World,Graham’s work illustrates the extent to which he and the poets are best read in dialogue as fellow travelers. Take his “March 31, 1966” (1970), which calculates a series of distances from his body:

1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000.00000000 miles to edge of known universe

100,000,000,000,000,000,000.00000000 miles to edge of galaxy (Milky Way)

3,573,000,000.00000000 miles to edge of solar system (Pluto)

205.00000000 miles to Washington, D.C.

.38600000 miles to Union Square subway stop

.11820000 miles to corner 14th St. and First Ave.

.00367000 miles to front door, Apart. 1, 153 1st Ave.

.00021600 miles to typewriter paper page

.00000700 miles to lens of glasses

.00000098 miles to cornea from retinal wall[3]

Whereas minimalist art of the prior generation strives to evacuate any trace of the ego or self, Graham’s Conceptualism seeks a renewed place for the physical body. The pendulum has not swung entirely back to the heroic masculinity of abstract expressionism — the above is hardly abstract — but Graham’s work certainly comes close through its self-aggrandizing of the artist creator. The work is like a Ptolemaic universe in which Graham is the center of all Creation.

These works all focus on the human body, but where are the other humans? Like Kenneth Goldsmith’s Fidget (2000) and Soliloquy (2001), the works portray or inscribe a self that is hermeneutically sealed off from others. If there are other voices or bodies (e.g., taking Perreault’s measurements, caring for Graham’s apartment), they are placed under erasure.

Not so with Hannah Weiner. She published several poems that year in The World magazine that situate two bodies in conjunction with one another, like friends or a couple. The poems “Hannah” and “Peter” that appear two issues later in The World are difficult not to read as a response to Acconci and Perreault:

PETER

Peter’s foot is attached to Peter.

It is attached to the ankle bone

adjacent to the leg.

This is true of the left foot

and the left leg

and the right foot

and the right leg

Peter’s leg is attached to Peter’s hip bone —

and this goes on, in the usual way,

until we havethe complete

Peter.

HANNAH

Hannah’s hand

is attached to

Hannah’s wrist.

What if it missed?[4]

Like Acconci’s and Perreault’s poems, “Peter” is constituted by an anatomy of body parts that make up “the complete / Peter.” The second poem “Hannah” is a variation of the same theme, but it swerves on a question of incompleteness — perhaps a phantom wrist — that is incompatible with the sealed-off bodies of Acconci and Perreault (and Graham). Further, Weiner’s poems appear side by side as if to suggest an intersubjective space in contrast to the individualism of her male peers. Weiner’s poems rely on adjacent bodies — a dialogical “hello.” Similarly, her Code Poems from the same era require a plurality of performers. The Code Poems are about call and response, like two ships in communication with one another on high seas. And her Fashion Show Poetry Event is an ambitious collaboration of artists and poets that displays body after body after body parading down the runway. This is to say, her mode is already the polyvocal long before the clairvoyant poems of the 1970s and later. Weiner is a foil to Simmel’s blasé mentality because she welcomes the teeming metropolis.

1. Vito Acconci, untitled, The World 11 (April 1968): np.

2. John Perrault, “Measurements,” The World 11 (April 1968): np.

3. See Lucy Lippard, Six Years: The Dematerialization of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997), 14. Lippard’s book, originally published by Praeger in 1973, was the first major critical discussion of “March 31, 1966.”

4. Hannah Weiner, “Peter” and “Hannah,” The World 13 (November 1968): np.

Edited by Divya Victor