'Antígona González'

On necrowritings and disappropriation

Mexican writer and academic Cristina Rivera Garza introduced the term disappropriation (desapropiación) in her essay book Los muertos indóciles (Tusquets Editores, 2013). Based upon the idea that language is a common good, the term indicates that the writer who works with documentation is actually disappropriating that language in order to give it back to the community. For the benefit of the collective. This testimonial is the poetry of the people. The question “Is appropriation OK?” has been rendered pointless. What writers take and where they take it from do matter, and this awareness is present in the poem known as “Antígona González,” a unique piece among very recent writing from Mexico. The question is not about appropriation anymore, but rather about: How is this writing bearing witness to this moment? How is it standing for its community? In what ways is it going to change the world?

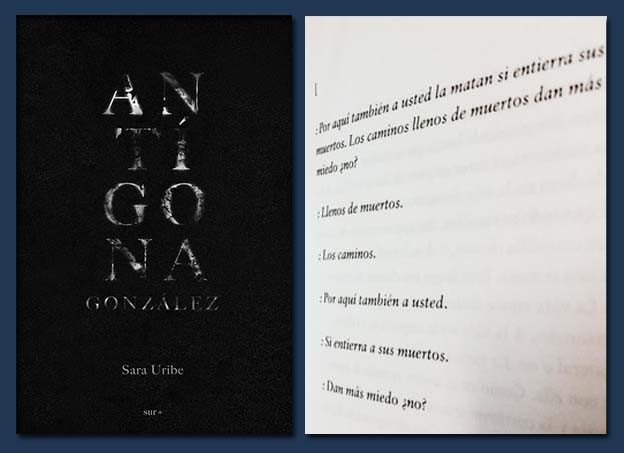

It begins with a set of instructions to count the dead. Sara Uribe’s “Antígona González” (Sur+ ediciones, 2012)[1] is a poem in which the speaker desperately looks for her brother’s dead body among the ruins of a nation embodied by its endless, stone-cold bureaucracy and the indifference of others. “Antígona González” is a poem that engages as one of the first full-frontal responses from contemporary writers in Mexico to the drug war that has devastated the country since 2006.

What happens when a body disappears? What context is drawn from the now empty outline of a disappeared person? What happens to the world when one is not able to retrieve the dead body of a loved one? “Antígona González” is a poem addressing politics. Latin American politics. Mexican politics. The poem is also an open critique of capitalism. A statement against the necropolitics we live by. Writing accordingly: the poem is necrowriting.[2] It is a poem that enumerates the consequences of depredation, censorship, and siege over centuries of oppression. It is a poem about the dead. Our dead. An account of the languages of loss and mourning (the feelings of modernity) in the twenty-first century. It is a poem about people in resistance. Communities who are resisting. Writing against power.

Violence has been systemic for over a decade in Mexico. Civilian carcasses can be seen on TV screens and newspaper front pages on a daily basis (this collaborative project intends to count them every day, “to preserve the memory of our dead, respectfully”). A state of terror has taken control of the population. De facto powers are in effect. And there can be no dissidence because that would imply certain death. It is a drug problem. It is a gun problem. It is an unnerving homeland-versus-other-land situation. We usually don’t care about people-next-door problems. But there are thousands of dead and disappeared whom power and its allies are not willing to acknowledge.

Since the first outbursts of violence on the streets of numerous Mexican cities, civilians have faced a hard time dealing with this “new order.” A new order that imposes deadly silence over the population. Rumor has it. The mainstream version (an official silence imposed by the governments) is that executions and mass murders are the result of old and new disputes among the drug cartels contending for dominion. Fighting, ironically, for territory within a disembodied society in an even more precarious environment. Nobody cares if civilians get killed just for being in the way. Nobody cares about the disappeared or about their families. In spoken and written texts, rumors of imminent attacks, or about a friend or relative who was recently kidnapped, or another who has been missing for several months, spread and frighten citizens. Every aspect of daily life is codified.

“Antígona González” embodies this language. Brought together via appropriation, juxtaposition, and performance, the sources for the text consist of news reports, testimonials, and poems. It is a courageous alternative version against the official silence through the language of commonality. The words of the community come together in this Antigone who is all too aware of the existence of previous Antigones who have also been looking for the bodies of their dead loved ones among the ruins of destruction. “Antígona González” is an activism device written in the poetics of despair, like a Greek tragedy condemning one of the greatest tragedies of the twenty-first century. An ongoing tragedy.

“Antígona González” gestures towards the ideas of Mexican artist and writer Ulises Carrión (1941–1989) who wrote (c.1975) that “Plagiarism is the starting point of the creative activity in the new art.”[3] But the poem is speaking from the present of the community in which it has been written. The poem is rewriting the present. This very moment. It is written with the community as a whole. The poem is another way to say: “As we speak.” We are all speaking through the piece. The language we all share as a community is embedded in the piece. It is alive. The strategies in this work by Sara Uribe engage in a political discussion that is long overdue, that needs to expand, and that deserves more attention.

1. The English version of Antígona González is by John Pluecker, forthcoming from Les Figues Press.

2. Cristina Rivera Garza, Los muertos indóciles: Necroescrituras y desapropiación (Ciudad de México: Tusquets editores, 2013).

3. See Ulises Carrión, “The New Art of Making Books,” Kontexts 6–7 (1975).

Edited by Divya Victor