The thick and the slow of knowledge

On the poet-scholar

Fidelity to the shapeliness of poetry, in an academy of prose, because knowledge is inseparable, we insist, from the texture and pace of its approach. Knowledge is not front-loaded, though the presiding timeline of production demands it be so. It’s a dawning: ambient, but nonabsorptive, with myriad ports of exit and entry.

And fidelity to scholarship, if scholarship signals the ritual of seeking and transcribing what exceeds one’s own, immanent domain, because knowledge as music can only ever be choral (as the Old English “school” conveys in meaning “choir,” or “band, troop, company,” appearing chiefly in verse): reverberating among voices made current by writing, but never merely coeval.

The writer whose hyphen denotes everybody’s discomfort with her being neither here nor there because devoted to shifting material works in spite of the disciplinary expectation that thought knows where it’s going, is to be delivered in terms on which it has “landed,” on which we agree. (“Because they liked me ‘still’ —”) Thinking has to found its own idiom continually to be thought.

The hyphenated writer whose method emerges in wayward relation to prevailing brands, because evolved in empathic relation to materials unsponsored and at hand, as in translation, cultivates a transfiguring humility with respect to poeisis as art: laboring in the glacial tempo of study, in the awareness that others have been here, over and over, over and upon one another in the sedimentation of collective thought — and that any literary scene nursed by the amnesia of blindered publicity, appearance, and feed rarely strains far enough beyond the current syntax of the possible to effect a tectonic shift.

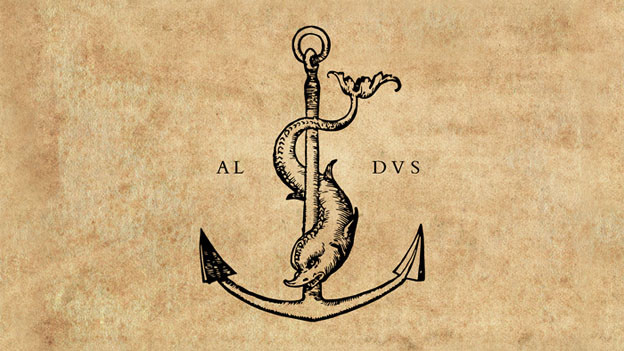

The radical Venetian publisher Aldus Manutius gave poetry both the gift and the delusion of autonomy when he stripped his editions of the exegetical apparatus, allowing Dante’s 200-year-old comedy to subsist independent of theology, and sonnets to be carried in the hands. Hence the motto festina lente, “speed up slowly” — granting poetry the quickness of immediacy (signified by the dolphin) and the delay (the rhythm-giving anchor) of its unmanagement on the page.

The thicket of transcribed voices the scholarly tradition anticipates, given so little room, buried on the page, tends to map only parasitic relations, hierarchies, or agons, rectilinearly. This convention can hardly accommodate the reciprocal interference between an object generative of the fascination or disgust antecedent to knowing and the being in its thrall: a transformation in which “I am not I any longer when I see,” as Gertrude noted.

Criticism committed to fascination will always have a labyrinthine relation to precedent and explanation, multiplying alignments as it seeks revised outlooks and grounds.

And poetry committed to knowledge existing as matter unappropriated by consciousness will seek likewise to document the struggle of its absorption as form.

The knowledge I’ve accumulated over time from the writings of the writers surrounding this table and past I’ve taken in as rhythm, as acts of patterning and interference, plurioblique. The knowledges of their books inhere as phenomena of facture and interpretation — they’re ways of doing, on the move.

Thinking that takes the shape of a continual negotiation as with the tides, of listening for an object’s countervailing logics, can raise suspicion among scholars: it is no “archaeology,” having failed to assume the noble trope of critical distance. This writing takes on bodily awkwardness: it sits intractable on the page, at once too-slight impression and fat with material.

But if the transformative ideal of poetry as a repercussive pull on the language in which we listen and see and act is to take effect in research and pedagogy, and the ideal of poetry as research is to exceed the superficial incorporation of information as decorative engagement effect, we need to defend the value of the poetic as a means of thickly knowing: not a knowing that aspires to transcend the structures which condition our sociability and governance as objects of global economies, citizens of national constructs, and members of discursive provinces, but one that seeks to trace and press against them — to recreate them, in the measure not of payoff, but of debt.

Edited by Margaret Ronda