The severity and sympathy of Ezra Pound

A newly translated 1928 letter to René Taupin

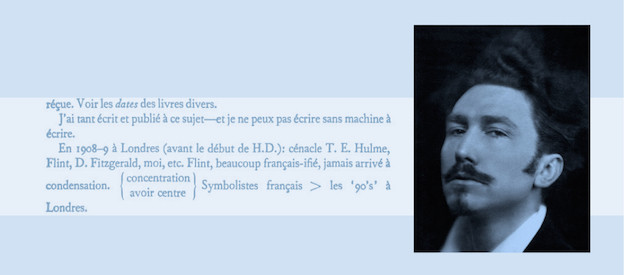

Blustering, condescending shorthand. Unflinching, self-righteous conviction. These hallmarks of poet Ezra Pound’s prose can be found throughout the seemingly impossible volume of his private correspondence. His jumbled and effusive style can be daunting to would-be readers. One such letter, written in 1928 to academic and critic René Taupin, had until now been even more elusive to English-speaking readers, as Pound wrote it in Taupin’s native French. The letter has been previously published, in its original French, in Letters of Ezra Pound: 1907–1941.

This author’s new translation, which follows this essay, illuminates the poet’s views on modernism, the general concept of intellectual influence, and other curiosities from his early twentieth-century vie litteraire. The letter was prompted by Taupin’s analysis of Imagism, the avant-gardemovement Pound, an American expatriate, had helped found in London after the dawn of the new century. Taupin, then chairman of romance languages at Hunter College, asserted that Imagism was almost inseparable from earlier French Symbolists (an argument which would culminate in his 1929 book, The Influence of French Symbolism on Modern American Poetry). For Pound, Taupin’s assertions belittled what he believed to be the unique accomplishments of his own literary movement.

Pound’s letter to Taupin serves as his rebuttal. Due to Pound’s scattered, almost stream-of-conscious writing style, passages of the letter are dissected here to better follow his logic, beginning with his opening:

Of course, if you permit an inversion of time, in some Einsteinian relativity, it would seem likely to you that I’d received the idea of the image from the poems of Hilda Doolittle, written after that idea was received. See the dates of the various books.

To lay the base for his argument, Pound painstakingly makes a case for a less direct influence on Imagism from modern French writers, asserting that he and his cohorts arrived at their conclusions more or less independently. He describes trademarks of his own style as “[v]ery severe self-examination — and intolerance for all the mistakes and stupidities of French poets.”

Pound goes on to trace the general flow of poetic innovation from French writers of the late nineteenth century through Symons, Baudelaire, and Verlaine. “Certainly progress in the poetic technique,” he admits. But it is from Arthur Rimbaud that Pound traced the origin of modernist writing, a fact in general consensus today.

That which Rimbaud reached by intuition (genius) in some poems, created via (perhaps?) conscious aesthetic — I do not want to ascribe him any unjust achievement — but for all that I know. I’m doing an aesthetic more or less systematic — and could have named certain poems of Rimbaud as example. (Yet also some poems of Catullus.)

And it is certain that apart from some methods of expression — Rimbaud and I have but a point of resemblance. But almost all of the experimentation, poetic technique of 1830-up to me — was made in France.

Experimentation perhaps, but not progress, continues Pound in signature frankness.

Since Rimbaud, no poet in France has invented anything fundamental. There were interesting modifications, almost-inventions, mere applications.

Pound pointedly disassociates himself from direct French influence, positing instead shared influence from earlier achievements, going all the way back to the ancients. Here he begins to question the theoretical limits of poetic influence between the two languages.

With all modesty, I think I was already oriented before being familiar with the modern French poets. That I took advantage of their technical inventions (Like Edison or any other man of science benefits from discoveries). There’s also the ancients: Villon, the Troubadours.

It is likely that France has learned from Italy and Spain. England from France but that France cannot absorb anything or learn from the English.

Does one English language exist to express the lines of Rimbaud? I’m not saying a translator capable of this, but if this language exists? (As a means) — and since when?

Of that balance, you must find the right relationship — at least on the technical side.

Not to completely dismay the reader with an endless list of indictments, Pound does at points rein in his rhetoric. He concedes that the seed of the French modernists must be somewhere present, albeit faintly, in his own work and that of the Imagists. To punctuate, he makes reference to an idiom from Taupin’s native French.

But indeed: the idea of the image must be “some thing” of the French symbolists via T. E. Hulme, via Yeats, via Symons, via Mallarmé. As bread owes something to the wheat winnower, etc. So much happening in between.

I believe that the influence of Laforgue (from Eliot) or Maupassant on America often came second, third, fifteenth hand.

Justifying any blatant offence at his bald treatment of French literature, Pound inserts a postscript mid-message, as though he thought perhaps at that point to give it a rest before continuing.

P.S. I think that my severity toward the reputation of French literature is preferable to the effusions of Francophiles or parasites who seek to pass of bad French poets as top rung. We build a more stable glory by aspiring to introduce solid authors (as many as the number they ram in, thrown there into puddles, swells, etc.).

Thus Pound finds, or perhaps seeks, common cause for a higher caliber of contemporary letters. For all Pound’s pains to set the record straight, a reader risks losing sight of his more benevolent excuse for anything borrowed, consciously or otherwise, from other writers. At these points, the poet reveals himself in a manner often lost in his blunt tirades: as an American genuinely concerned by the state of arts and letters in his homeland.

Sometimes we pick up, or are suddenly “influenced” by an idea — other times fighting against barbarism, we seek support — arming ourselves with the prestige of a civilized man, and recognized, to fight American imbecility.

I have quoted Gourmont, and I just gave a new version of Confucius’ Ta Hio, because I find there formulations of ideas that appear to me (potentially) useful for civilizing America.

Finally, the poet transcends the argument in question, pontificating more universal truths regarding intellectual influence and the spread of ideas. It would take someone like Pound, who in fact saw himself on a sort of literary crusade against decadence, to distinguish deliberate association with just cause as being nobler than even unconscious imitation. As he explains to Taupin, “I rather revere good sense over originality.”

Full translated text: A letter from Ezra Pound to René Taupin

Vienna, May 1928.

Dear Sir: Of course, if you permit an inversion of time, in an Einsteinian relativity, it would seem likely to you that I’ve received the idea of the image from the poems of H.D., written after that idea was received. See the dates of the various books.

I have written and published so much on the subject — and I cannot write without a typewriter.

In 1908–9 in London (before the debut of H.D.): circle T. E. Hulme, Flint, D. Fitzgerald, me, etc. Flint, much French-ified, never arriving at condensation.

{concentration/ having center} French Symbolists > the “90’s” in London.

Contemporary meaning ~ equivalence

Technique of T. Gautier in “Albertus.”

Beside all that, I have printed material. See Pavannes et Divisions and Instigations. Can one be the cause? — here now or in Rapallo in July?

English poetry (the same language < French roots Consider elements of the language: “Anglo-Saxon”

Latin (church — law) Prin.

2nd French 1400

Scientific Latin

greek. . “

French influence on me — relatively late.

Reports French > English. via Arthur Symons etc. 1890. Baudelaire, Verlaine, etc.

F. S. Flint special number Poetry Review, London in 1911 or 1912. Strong difference between Flint: (tolerance for all the mistakes and stupidities of French poets.) Me — Very severe self-examination — and intolerance.

Would-be “Imagists” — “bunch of groups” too lazy to support severity of my first “Do not’s” and of the 2nd clause of the manifesto “Use no superfluous word”

Certainly progress in the poetic technique. — France leading the way. Gautier “Albertus” England 1890–1908. That which Rimbaud reached by intuition (genius) in some poems, built in (?? maybe) conscious aesthetic — I do not want to claim an unfair glory — but for all that I know. I’m doing an aesthetic more or less systematic — and I could have named certain poems of Rimbaud as example. (But also some poems of Catullus.)

And it is certain that apart from some methods of expression — Rimbaud and I have but a point of resemblance. But almost all of the experimentation, poetic technique of 1830-up to me — was made in France.

Actually “poets,” that’s another matter. There was Browning (even Swinburne), Rosetti, E. Fitzgerald, who interested themselves more in topics on the matter of new expression than in the processes of expression.

You have in Poetry, Chicago, (1912, I believe) my first citation of contemporary French. The era of unanimism.

With all modesty, I think I was oriented before being familiar with the modern French poets. That I took advantage of their technical inventions (Like Edison or any other man of science benefits from discoveries). There’s also the ancients: Villon, the Troubadours.

You will find in my The Spirit of Romance, published 1910, that which I Knew before addressing French moderns.

It is likely that France has learned from Italy and Spain. England from France and that France cannot absorb anything or learn from the English. (? Problem — not dogma.)

Another dissociation to make: sometimes we learn, or suddenly “influence”

an idea — other times fighting against barbarism, we seek support — arming ourselves with the prestige of a civilized man, and recognized, to fight American imbecility.

I have quoted Gourmont, and I just gave a new version of Confucius’ Ta Hio, because I find there formulations of ideas that appear to me useful for civilizing America (tentative). I rather revere good sense over originality (that of Rémy de G., that of Confucius).

To return to the subject: I hardly believe the French poetry must have been rooted by a good English or American poetry, but the technique of French poets was certainly in a state to serve in the education of poets of my tongue — from the time of Gautier until 1912.

Of the essential poets, having this preparation, it occurs time and again in Gautier, Corbiere, Laforgue, Rimbaud. Since Rimbaud, no poet in France has invented anything fundamental.

There were interesting modifications, almost-inventions, applications. (See Instigations or my number of Little Review on French Poets.)

I think Cocteau, who you glorify as metteur-en-scene and neglect as very good minor poet, did something to free the French language of its cuffs (Poésies 1920). That’s for the French language — utterly useless for us who write in American — Meaning: invention of local utility.

Perhaps you will be an instrument of thought. If you ask yourself the question.

Does one English language exist to express the lines of Rimbaud? I’m not saying a translator capable of this, but if this language exists? (As a means) — and since when?

Of this balance, you must find the right relationship — at least on the technical side.

If you’d like, you can send me your study before printing it and then I could indicate the differences of view, or the errors (if any would be there) of fact, minor chronology, etc.

P.S. I think that my severity toward the reputation of French literature is preferable to the effusions of Francophiles or parasites who seek to pass of bad French poets as top rung. We build a more secure glory, by wanting to introduce solid authors (as many as the number they ram in, thrown there into puddles, swells, etc.)

I think Eliot, whose first poems showed influence of Laforgue, has less respect for Laforgue than the respect I have for Laforgue.

Gautier I have studied and revere. What you take as influence of Corbiere is probably directly influenced by Villon.

[Villon] by Tailhade superficially

[Tailhade] by Jammes !! I hope not.

As for the sonnets? Catullus, Villon, Guido Cavalcanti, some Greeks who were not Pindar, some Chinese.

Und ich überhaupt stamm aus Browning. Why deny his father?

Symbol?? I have never read “the ideas of symbolists” on that subject.

In my youth I had maybe received some idea received from the Middle Ages. Dante, St. Victor, God knows who, revisions via Yeats (the latter full of unknown symbolism — via Boète, French symbolism, etc.) — but I do not how to uncover the traces.

I recall nothing of Gourmont’s on the subject of the “symbol.”

My reformation:

1. Browning — devoid of superfluous words

2. Flaubert — the precisely correct word, presentation or observation

Metric reform more profound — as of 1905 we began, before knowing French moderns.

I “launched” the Imagistes (anthology Des Imagistes; but I must be dissociated from the decadence of Imagistes, beginning with their subsequent anthologies (even the first of these anthologies)).

But indeed: the idea of the image must be “some thing” of the French symbolists via T. E. Hulme, via Yeats, via Symons, via Mallarmé. As bread owes something to the wheat winnower, etc. So much happening in between.

But also to Catullus (not Mendès) — Q. V. Catullus — who had a strong concept net from the preceding several thousand years.

But my knowledge of French modern poets and my propaganda for these poets in America (1912–17–23) came in a general sense after the inception of Imagism in London (1908–13–14). I believe that the influence of Laforgue (from Eliot) or Maupassant on America often came second, third, fifteenth hand.