'Young Knowledge': Signature poem of Robin Hyde?

Mary Paul

Robin Hyde’s “signature” long poem, “Young Knowledge,” written in late 1936, conjures up a tonal ambiguity. Is the poem ironical about youthfulness (and the impossibility of it being hopeful in hard times) and the associated youthfulness of her country? “Young” tagged to “knowledge” is a fluid signifier — how to read it?

At the time Hyde wrote this poem, many of her contemporaries, particularly writers, artists, and intellectuals, felt that the earlier socially mixed and idealistically egalitarian settler society had disappeared; New Zealand had become as conformist and socially divisive as “the old country” that emigrants had been so keen to leave. Some, for example poet A.R.D. Fairburn, also felt their country was becoming increasingly Americanized — as in consumerist. In “Utopia,” a satirical section of his long poem Dominion (1938), Fairburn paints his country as prematurely aged:

from the bargain shops and basements

at dusk, as gazelles from drinking;

the men buy evening papers, scan them

for news of doomsday, light their pipes:

and the night sky, closing over, covers like a hand

the barbaric yawn of a young and wrinkled land.

Contrary to this, and understandably given the significance of a publication that brought the poet back into attention, Michele Leggott uses the title of Hyde’s poem both for the 2002 Young Knowledge: The Poems of Robin Hyde (AUP, 2002) and for the section it is included in within that volume more positively.

“[Y]oung” and “knowledge” in this context suggests the wisdom of the poet and the loss of her rich understanding of the world when she died at only thirty-three in London in 1939. Youth is also for the nation. Leggott glosses Hyde’s writing at this time as an “increasingly self-conscious search for the ‘young knowledge’ that will fit the person, her place, and the generation she writes from.”[2] The implicit parallel here is with Allen Curnow’s world-famous-in-New-Zealand lines: “Not I but some child born in a marvelous year/will learn the trick of standing upright here,” from “The Skeleton of the Great Moa Canterbury Museum, Christchurch.”

But there is something place-marking about nationalism characterized broadly as a search for where to belong, as against a critique of the disappointment with the young nation and its origins — which I think now we can understand as Hyde’s more nuanced take. Seen in this way, Hyde is teasing out the idea of young knowledge as fresh, optimistic, even open and wondering.

In Leggott’s arrangement, “Young Knowledge” appears after another use of the epithet “Young” in the opening line of the previous poem, “Essay in Treason.” In this poem the poet and people who have become “Yesterday” watch the present — hoping it will not be the future:

“She” and “He” are growing up and older without roles or any channel for their emotions. He can’t fight and she can’t love, but they have the sword and babe to do injury with, and to. This is a way of explaining growing up in modernity (without agency or roles) but also growing up and growing older caught in a history when those who plot and plan the present, and hence the future, care nothing for the flourishing of ordinary lives.

Similarly, Hyde identifies “Young rebellious knowledge,” as “chidden /Dunce at its school” — indicating Hyde’s mocking disillusion with authority. Hyde’s pessimism is not only about individual lives but also public history — war and politics. It is informed by the writing of her first full-length prose work, the biofiction Passport to Hell, dramatizing the Great War experiences of Douglas Stark, written from interviews in 1936. Her account shows how his upbringing without a word of comfort made him vulnerable to exploitation as a soldier. There is no patriotism on show.

Hyde also wrote about the consequences of societal aggression on the fellow patients she met at the Lodge (a voluntary ward of Auckland Mental Hospital where she lived and wrote from 1933–1937), men and women scarred by a cruel mix of punitive family culture, societal judgment, and economic desperation.

Painful kinds of knowledge “sharp, sudden,” play out in alternate stanzas. There is knowledge that one person uses to injure another — the arrogant “grudging fellow” epitomizes the person you shouldn’t be with when you are feeling vulnerable. Other knowledge is “a thunder in the night,” learning the fact of tyranny from experiencing or witnessing acts of violence:

Knowledge is also a presentiment or warning — something you feel driven to share: “the hard impatient message in the breast.” Here knowledge is both something conveyed and the energy to tell it in “big words like bloodshot smoke behind old houses.” Knowledge is an indexical sign — a warning that houses will burn.

This kind of knowing can also be an activity or aspect of “fretted minds,” the bewildered. Hyde uses war imagery, topical to her time, to represent this — so the disturbed and mad are “soldiers, jagged troops” and explorers who search with “circling torches.” Knowing is tentatively approached and painful:

That only is your knowledge. Take and bear it.

This tough knowledge can be a consequence of telling what you knew and few wanted to hear (of being a Cassandra or a whistle blower), but also of having to live with having tainted, or at least having touched and changed, the future:

These lines hint at a personal anxiety about having spoken truths that others don’t want to hear. One example was Hyde’s decision to write about the young soldier Starkie, who was insubordinate yet wildly brave to the extent that he was recommended as many times for military honours as he was court martialed. Her book Passport to Hell tells of the horrors and absurdities of war from his private soldier’s point of view, and though when it was published in 1936 it was regarded as searingly truthful, it retains its shock value. Recently when I was taking part in a discussion of war writing on a literary festival panel I was fascinated to hear a fellow panelist and military historian express the opinion that the foolhardy “Gunner Stark” ought to have died, suggesting perhaps that it would have been preferable if his explicit story had not survived.

“Young Knowledge” was probably written in late 1936 or early 1937, after the autobiographical writings published in Your Unselfish Kindness and close to another autobiographical piece, A Home in this World. There weren’t any diaries composed then, but there were letters and travel articles in the Railways Magazine. We know that Robin Hyde visited the remote settlement of Arahura (the subject of the last stanza) on the West Coast as part of a travel writing assignment. She was on a leave from the Lodge at Avondale Mental Hospital, on a trip to Dunedin at friend and patron Downie Stewart’s suggestion and expense. She took a round-tour and visited Stewart Island, Queenstown, and returned north via the West Coast (traveling by rail from Christchurch), then flying from Nelson to Wellington — and back to the Lodge by Christmas.

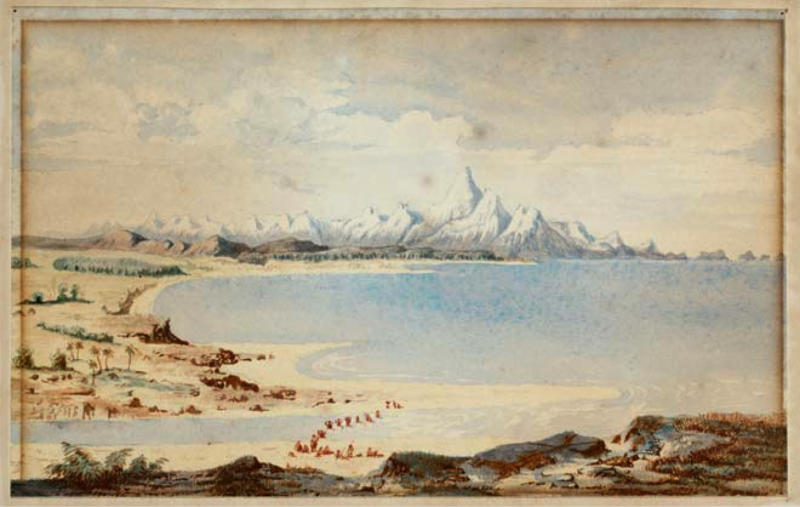

Arahura lies on the coast north of Hokitika and is one of the remote areas the painter and surveyor Charles Heaphy visited in 1846, travelling on behalf of the New Zealand Company. As she travelled Hyde was reading his journals and imagining him in that landscape:

The poem ends with Heaphy’s anticipation of the inevitable change that European settlement would bring:

Read in our current climate the poem’s dark mood is once again familiar; but the poem also takes good from bad — suggesting how not to be alienated, and how to transform the “moral distress” that many experience in not being able to fix what is unjust. The shift is to a knowing that is so companionate that it is hardly knowledge at all — because there is no knower or known.

The clue to understanding how the mood of the poem wavers between these compass points from dark to companionate knowledge (and how this supports Hyde’s creativity) is in Hyde’s life writing (journal, diary, and autobiographical examples) composed while she lived at the Lodge. The last piece in the collection, Your Unselfish Kindness: Robin Hyde’s autobiographical writings, is an unfinished piece (probably only latterly titled “Essay on Mental Health in New Zealand”) written shortly before this poem.

In that essay Hyde tells how she had reviewed a book in 1926 by American Jane Hillyer on the experience of institutionalization for mental breakdown — not guessing then, as she says (perhaps disingenuously), that she would ever have “a personal interest in the subject” of “how one mind could come back from the darkness and, like Persephone out of Hades, came laden with flowers.”[3]

Like Jane Hillyer, Hyde’s experience in a voluntary ward at Auckland Mental Hospital in Avondale was of newly enlightened psychiatry: “the courageous modern attempt to treat mental patients as human beings,” that enabled her to “come back from darkness, ” particularly with the assistance of psychiatrist Dr. Gilbert Tothill, whom she could trust and confide in. Hyde connected her healing with Jungian ideas. She describes Jung “as understanding the Heaven of the neurotic — that passionate desire to make the world over and over again which is perceived in so many alienated from normal life,” and Jung’s idea of the usefulness of the broken force of thwarted love. She also mentions Jung on Goethe’s “fantastic flowers, how Goethe when he sat down and lowered his head vividly conjured up the image of a flower then saw it undergoing changes of its own accord.”[4]

Hyde’s notes link healing with concentration on detail. For a fellow patient at the Lodge she imagined a series of daily “Present exercises”: “I would set him to do … essays or sketches that describe as minutely as possible his immediate surroundings and the happenings of the moment” that “draw the faculties to the fortress of the real” and “away from the subject of [his] endless imaginary woes.”[5]

Mindfulness could be a contemporary name for this technique, but Hyde extended it further, into rapturous imagination of being part of the detail, as in the opening stanza of the poem:

And in the fifth stanza as the garden where all systems thrive together:

Companionate knowledge is neither young nor old but a feeling of belonging in the world, waking up and singing because you know you are a bird: “lost in the garden; smooth to tread is knowledge” when there is no rift between knower and known.

This article adds to the public conversation about Robin Hyde’s poem “Young Knowledge” hosted as part of the National Library New Zealand poet laureate programme by the Auckland Central City Library (Friday, 26 October 2012). Ian Wedde, 2011-13 New Zealand Poet Laureate, was in conversation with Murray Edmond, Michele Leggott, Mary Paul, and Iain Sharp. Young Knowledge: a public conversation.

Arahura River Mouth, 1846. Charles Heaphy sketched this scene of Arahura on the West Coast about 1846, well before gold was discovered in New Zealand. Subsequently, an unknown watercolourist copied the scene to produce this painting.

Cracked mirrors