Messages from the Antipodes

Ted Jenner

In New Zealand the poetic generation of 1946 surveyed the boundary fences, then jumped over them. From the late 1960s this generation has set both the poetic and the critical parameters for general and specialist discussion. Career-long attention has been given to Ian Wedde, Bill Manhire, and Sam Hunt, who were all born in a year of notable publications such as The quest: words for a mime play (Charles Brasch), Jack Without Magic (Allen Curnow), The Rakehelly Man & Other Verses (A.R.D. Fairburn), Summer Flowers (Denis Glover), and Seven Sonnets (Kendrick Smithyman). Edward (‘Ted’) Jenner also belongs to this mid-century lift in New Zealand literature, and while he is not mentioned in despatches as often or as fondly as his peers, he deserves to be.

A poet whose focus is often ancient Greek texts, Jenner’s approach has been described by Jack Ross as ‘postmodern classicism.’[1] And this hits the memorial brass on the head. In part it explains, although it cannot justify, his neglect. For much of his life he lived and taught in Malawi, rather than impressing the gatekeepers of literary New Zealand; critical appraisal of his work is thus lacking. That said, there has been a late harvest of his oeuvre — and this feature is one small part of it. The two poems published here underscore his unconventionality as a New Zealand poet; they show how cleanly Jenner can suture familial knowledges with the global, so that Henry Vaughan, the Simpsons, and a parent’s death are effortlessly connected.

Percutio no. 10 (2016). Special issue devoted to two projects by Classicist and poet Edward Jenner. ISBN 978-1-877441-53-0.

The Arrow That Missed. n.p.: Cold Hub Press, 2017.

The Sprinkler

–Lisa Samuels

–Ashwood, Melbourne, 2014

The Sprinkler: A Commentary

A few years ago, I became fascinated in the sound of swishing and meshing waters made by sprinklers! I made a few notes on the ‘soundscapes’ of these devices, intending eventually to write a poem about at least one of them in the manner of Francis Ponge (1899–1988), the French poet who wrote intricate descriptions of very common objects in (usually) short prose poems. Because they grapple with the problems of expressing the nature of, for example, a snail or a telephone in a medium quite alien to them, i.e. human language, these texts say as much about their author as they do about swallows and washing machines. In a suburb of Melbourne, Australia, in April 2014, a sprinkler running nightly on the lawn of a friend’s house confronted me with an ultimatum: the time has come; explore and express me! — but not in the Ponge way, the object in all its dense and unfathomable ‘thingness’; run away with my ‘music’ and take it from there!

Apart from ancient Greek poetry, another passion of mine is modern French poetry, above all the prose poems it features so prominently. I am particularly interested in the way this sort of poem gives its practitioners (Fargue, Deguy, Char, Ponge) a flexible and adaptable approach to poetry in both content and technique. Consequently, I saw far greater possibilities of giving free rein to the ideas I wanted to express in prose than in the use of a syllabic verse or stanzas. The prose poem is at last gaining some currency in the Anglo-Saxon world, even in New Zealand where it has been regarded with a degree of suspicion. And yet so much verse I read these days in this country sounds to me like prose chopped up into its phrases and units of meaning for the sake of emphasis or convention, my own included. ‘Meadowbank, One Evening,’ for example, I regard as a mixture of prose poetry (the first seven sections) and verse (the last two). Sections nine and ten, on the other hand, consist of unmetrical lines (without a beat- or syllabic-count) cut up into short units for the sake of variation and convenience.

The twisting and twining waters of … the ‘hitherandthithering’ muzak of … a sprinkler? This was another attempt at a poem reproducing sounds just as in ‘A Concise Natural History of Southern Malawi’ (Writers in Residence and other captive fauna, 2009), I tried to embody as many bird and insect calls as I could in the texture of the poem. The metallic rasping of the chorus lines (‘tiktiktiktiktik,’ etc.) represent the sprinkler as a kind of mating insect, a ‘hydropter’ (‘water-wing’) as I call it (a shameless neologism!) with a strident chirruping. Alliteration, especially of s and b, abounds, but the ‘hydropter’ does more than scatter phonemic particles that mimic the characteristic clicks and smacking lips of the Bantu languages; it releases a cascade of images that recreate the exile of the Jews and their search for the Promised Land along with Aboriginal myths of the freeing of the waters. The hose becomes the Rainbow Serpent, the fertility spirit associated with the regenerating rains, while the whirled and whirling waters and the multiple droplets and beads of ‘rain’ recreate the bunyip and the mimi, respectively the monsters and the ‘good fairies’ of Aboriginal myth and lore. The phrase ‘at this end of the wide world without end’ is taken from Michel Butor’s Letters from the Antipodes (1981), which is the translation of a section of a much longer work of his called Boomerang (1978), based on the author’s three visits to Australia. The Alcheringa that the poet is attempting to create in his backyard is the ‘Dreamtime,’ the age of the first ancestors of mankind, the half-human Beings who, in their journeys, made rivers, trees, waterholes, and plains.

Eventually a voice from the sprinkler, as it churns out ‘imitations of itself,’ has the temerity to accuse our poet of doing something very similar, i.e. churning out ‘simulations and representations of himself.’ I’m borrowing a line from Jean Baudrillard here and suggesting that poetic effusions and the critics’ responses, are, like those of the media, all preprogramed, whirling in constant, ever-widening circles around their chosen themes and subjects, each according to its established code or model. Drifting off to sleep on his hammock, the poet misses the poems he denied himself that night. But has he missed the poem? Hasn’t this simulation of his, this simulacrum, which even incorporates the critical response of the voice in the sprinkler, replaced the poems he missed by falling asleep? Isn’t the simulacrum of a poem just as real in this postmodern world of ours in which the simulacrum has become the real?

I wrote this poem in the summer of 2015, and it was first published in Victoria, Australia, in the Transtasman issue of the online Cordite Poetry Review in August the same year.

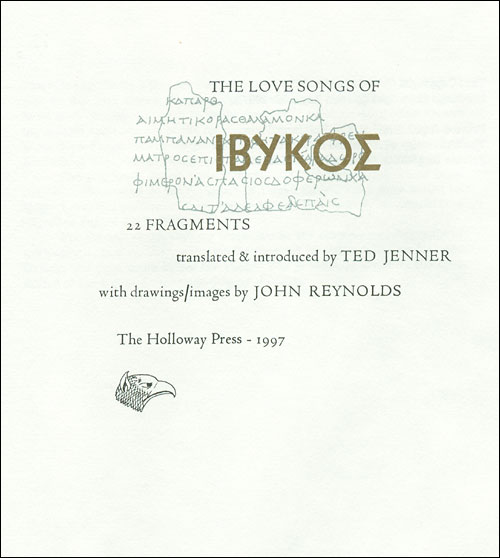

Ted Jenner, The Love Songs of Ibykos, Auckland: Holloway Press, 1997

Meadowbank, One Evening

i.m. Margaret Jenner 1921–1997

The nor’easter purses its lips at the windowsill of the Games Room, a stubborn

trumpeter with the massive dimples and swollen cheeks of the ward sister who

whistles down the corridor, beckoning for the bodies of her saints.

. . .

Birdsong and sunlight in the West Ward at evening.

A bouquet at Reception awaiting collection.

Grandfather clock chimes the quarter hours in the entrance hall.

The late sun in the North Wing is suffused with the colours of its curtains: orange

and gold, saffron and orange, a ruffled tawny gold.

. . .

High ceilings with the faint redolence of ginger and pepper throughout; a voice at

the end of a corridor begging medicine and forgiveness.

In the East Ward, the wallpaper is fleecy cirrus on a dark blue background. (The

angels have absconded with the trumpeter.)

. . .

There is a single chequered ball lying on the linoleum in Physio; a row of walking

sticks marching in step to the door.

On the ceiling, fluorescent lighting hums ‘like the angels,’ said Flanders to Homer.

‘And if you’re feeling lonely, it’ll keep you company day after day.’

. . .

Outside the entrance to Ward 3, the tropical fish describe slow, elegant parabolas,

their compressed sides covered with minute silver scales.

‘Nurse! Nurse!,’ cries a voice in the distant East Wing. ‘Help me! Help me! Help

Emily, please.’

A swordtail drifts closer to the glass, dips its tail and releases a stream of miniature

bubbles.

. . .

The calm and resignation of the evening prevails in the Community Hall, the

furniture subdued, somnambulant.

Both sexes assume a metallic sheen, clothed in the sun’s last rays, this film of

burnished copper.

. . .

Calm too on Sarah’s sterner face, like that of a matriarch on a marble sarcophagus,

right arm outstretched, extending a shallow dish to the invisible officiant,

Her teacup proffered to the duty sister passing down the West Ward, quickly casting

a glance at each of the eleven souls in her charge.

‘Which one will catch the Seventy-Seven before morning? (Who’s off upstairs

without legs or leave, then?)’

. . .

. . .

memories and morphine

standing in the doorway

of the draper’s shop

sheltering from the rain

with Pilot-Officer Banks

your first beau’s fingers

suddenly tightening

on your shoulder blades

.

the flying boots of dead airmen

you stacked neatly in the Nissen hut

jackets and goggles

hanging in rows, eerie

as the drone of a Ventura

feathering its propellers

at the other end of the ward

. . .

Ceilings in rooms where

insects of light catch

in a coil of midges

Ceilings in rooms where

you waited all night

to toss that net of midges

into day.

. . .

sit walk with us

vanish alone

to the horizon

you are not

lonely distant

as its light

Meadowbank, One Evening: A Commentary

My mother died of a ‘cerebro-vascular accident,’ in the words of her doctor, early in the morning of November 4, 1997. I finished this poem sequence in March 2015, and it was published in the literary journal brief towards the end of last year. Why was it published so long after the event?

The period of illness that led to my mother’s death was so protracted and painful that I hesitated to share the details and the circumstances with the public. The sequence (especially the first seven sections) was assembled from the remarks and observations I recorded in a notebook starting in July 1997 (about the time my mother found her closest relatives unrecognisable) and continuing until her death in November. She died in Meadowbank Hospital, an institution for the terminally ill in the suburb of the same name in the city of Auckland. Sections of the poem were first written in Malawi, Africa, when I was lecturing at Chancellor College, University of Malawi. The poem was abandoned soon after — I was dissatisfied with what I had written, and the subject matter once again seemed intractable. In fact, I didn’t approach the subject again until I had published two books that I had also embarked on in Malawi — a book of poems and short fiction and another on some funerary inscriptions in Ancient Greek. By this time, the first version of this poem consisted of a few fox-marked and dog-eared sheets of paper.

Several months of observations have been telescoped into a single evening. In the corridors of the hospital, there was always a draft (which I described back in July 1997 as ‘a strident hum never amounting to a wail’) and an almost preternatural light in the North Wing. The light suffusing the curtains and the curtains in turn suffusing the wards and corridors with their own warm colours form the central image of the sequence, the metaphysical aspect of which is at once suggested by the epigraph from Henry Vaughan (1621–1695). But Vaughan wrote about the dead vanishing into ‘the world of light,’ i.e. something approximating to the Christian conception of Heaven:

The patients in this poem of mine, a poem written by an agnostic, go into ‘a world of light,’ Heaven being merely one of several possibilities. There is an awkward tension, amounting to an acute irony (which I felt keenly at the time) between the metaphysical ‘world of light’ and the terrestrial light which mimics it in the wards and corridors. Continuing in this vein of cruel mimicry, the wallpaper is ‘fleecy cirrus on a dark blue background,’ the angels become ‘insects of light,’ and my mother’s spirit is asked to ‘walk with us’ though it is as ‘distant’ as the horizon’s light.

The pathos inherent in the situation is outweighed by all the awkward and acute ironies, as I noted back in 1997. The ‘walking sticks’ march ‘in step to the door,’ the fluorescent lighting ‘hums like the angels’ (a quip from an episode of The Simpsons), Emily’s mournful cries (‘politeness on the verge of despair,’ as I described it in the notes) are interrupted by observations of the tropical fish, observations which inform the description of the patients gathered in the Community Hall (‘Both sexes assume a metallic sheen’).

Sarah’s pose, ‘like that of a matriarch on a marble sarcophagus’ (seventh section) reminded me of the effigies on the lids of Etruscan sarcophagi, one hand clutching a shallow bowl of libation. The duty sister’s almost aggressively cheerful asides (‘Which one will catch the Seventy-Seven,’ etc.) are replaced by a voice urging my mother to take her painkillers. This shift to a personal focus occurs immediately after the duty sister’s questions which now begin to sound both leading and rhetorical.

My memories of my mother’s memories are somewhat hazy (why didn’t I take more notice of my parents’ reminiscences?), but I can vaguely recall an incident (rather innocent) involving a boyfriend outside a draper’s shop. As a nurse in the Royal New Zealand Air Force stationed at Rongotai Aerodrome, Wellington, during World War Two, my mother occasionally had to stack the belongings of dead airmen in the Nissen huts they had used as their quarters. The aircrew were being trained in the Ventura, a patrol bomber in operational service with the RNZAF in the Pacific.

In September last year, I made a return visit to Meadowbank Hospital, or rather its site. Its four stories had been reduced to large chunks of concrete, the demolition almost obscured by rows of apartment blocks. That is another detail which I could not work into the poem. Likewise the ‘Climbing Compassion,’ a rosebush in the back patio of my parents’ house which suddenly burst into flower two days after my mother’s death.

[1] Jack Ross, “Troubling Our Sleep: Ted Jenner’s Postmodern Classicism,” Ka Mate Ka Ora: A New Zealand Journal Of Poetry and Poetics no. 8 (2009).

Cracked mirrors