Circling an absent centre: The poetics of Joanna Margaret Paul

Cy Mathews

In 1978, Joanna Margaret Paul (1945–2003) published Imogen, a limited-edition book of poems dealing with the death of her infant daughter. Despite winning the Pen Best First Book of Poetry award, it received little critical attention. Only one brief review appeared in Landfall written by the then rising-star poet Brian Turner. Turner, while impressed with the book’s typographical layout — Paul was already an established visual artist — wrote of how he was “left drained” by its emotional intensity. The book, he concluded, was more of “an experience than a poem”: there just wasn’t “enough poetry” in it.[1]

At a time when the literary revolutions of modernism were already being disrupted by postmodernism, it seems strange to encounter such a narrow definition of poetry. New Zealand literature has become more diverse in the decades since (while retaining a strong core of conservatism: Turner has gone on to win a string of prestigious prizes, including the Poet Laureateship in 2003), yet Paul still occupies a marginal position. The issue is not that her work lacks “poetry,” but rather that until recently there has been a lack of easy access to her work. During her lifetime she published outside of the university publishing houses, releasing chapbooks or limited print-runs from small presses. In 2006, however, her poetry was introduced to a wider audience when Victoria published a selected works, Like Love Poems edited by her close friend and fellow poet Bernadette Hall.

Paul left behind a diverse body of material: she wrote poetry and prose, painted pictures, took photographs, took part in art installations, made films. Imogen may have been her first book, but she had been writing poetry for years prior to it. While her visual art was underappreciated for much of her life,[2] it is art for which she is most remembered in broader New Zealand culture: newspapers reporting on her sudden death described her simply as an “artist.”[3]

Paul’s art and writing are, however, inextricably linked together by several thematic and stylistic features. Foremost amongst these is, as Ian Wedde has put it, “a sense of order or form that resists foreclosure,”[4] the creation throughout her oeuvre of an open-ended structure of diverse yet connected parts. As Paul herself wrote in an untitled piece originally published in 1973:

I cannot write a sonnet

that opens from rooms to measured

rooms with windows partitioned into

panes

but

only

another

poem

called

CAVE

centre

hollowed from the

ever earth

no lights or limestone ornaments

but space

hollowed by the shape

of its

inhabitant [5]

These tropes of shape and space are integral to Paul’s work, but it would be a mistake to think that her’s is purely a poetry of typographic play and literary-historical references. Also common are the themes found in a short, less overtly visual poem titled “Lake Wiritoa 2”:

the water is ‘beautiful,’ ‘beautiful’

& ‘fucking lovely’

a thin woman

leans over a child with great

tenderness

the hills are yellow

a man’s body

white on

grey gold

water [7]

The colourful images of those final five lines frequent much of Paul’s work, yet her writing is never purely imagistic. As the early US imagists discovered, the visual intensity of the poetic image is frequently twinned with a tendency towards ossification; devoid of movement, the isolated image has nowhere to go, no direction to grow in, trapped in “still life.” Paul’s work avoids such stagnation by combining the image with other less static energies. In “Lake Wiritoa 2,” the energy is oral. While the second half of the poem presents painterly, almost abstracted images of the human body, water, and landscape, the first few lines ground these elements in the flux of everyday life: exclamations, an expletive, the soundtrack to a summer swim with friends and family in a small New Zealand lake.

Paul returns again and again to such everyday intimacies: her familiar landscapes of Dunedin or Whanganui, conversations with friends, excursions, everyday incident. In “Proper Names,” such subjects are combined with explicitly visual typographical elements. The poem begins:

When

the wave came

across the TOMBOLO

we laughed ANNA

pursued the floating kit

thermos lid & I

rescued the BUCKINGFORD

English mould-made paper

sodden but colours re

freshed the sky THALO BLUE &

THALO CRIMSON (the sea) the

empty beach, somewhat

vermilion

another wave came

200 yards &

recessed

leaving

the beach empty

of horses, my shoes,

SUZETTE with little

pierced black straps

ruined [8]

Again, the poem depicts everyday events: a painting trip to the beach, with the happy disarray of an unexpected wave soaking feet and art materials. As in “Lake Wiritoa 2,” the poem is filled with colour. Here, though, the proper nouns in capitals intensify the visual factor. In this piece naming functions as a kind of labelling, a stamping of meaning onto the page. Different categories of things — the name of a person, the technical name of a paint color, the brand of a shoe — become unified as visual elements, as objects. For Paul, this transformation is no mere technical exercise, but carries a profound emotional weight. In a moment that recollects (though on a far less tragic scale) Paul’s dedication of Imogen to her lost child, “Proper Names” swiftly becomes a poem of loss:

ANNA apologised

&

left

ANNA ANNA ANNA ANNA [9]

In the space of four lines, a living — a name meant to represent the presence of a friend — is transformed into an emblem of absence.

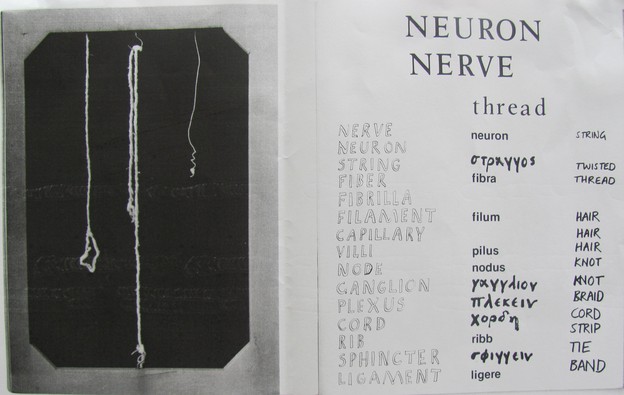

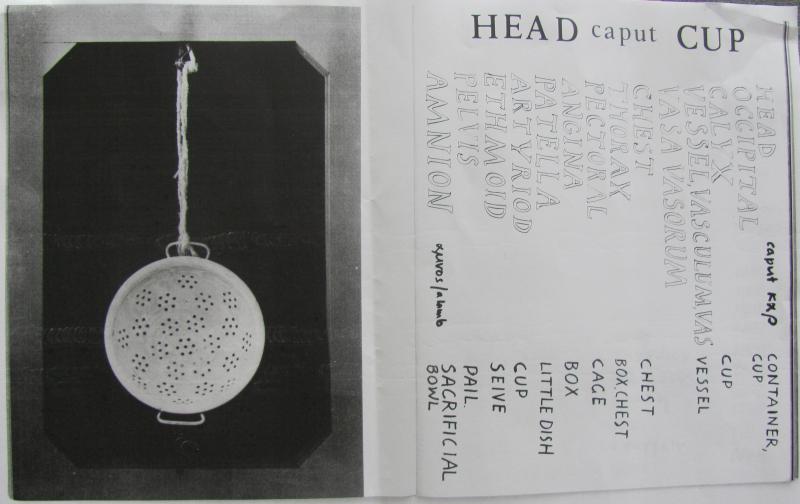

from Unwrapping the Body (Dunedin: Bothwell, 1970), n.p.

from Unwrapping the Body (Dunedin: Bothwell, 1970), n.p.

Such visual depictions of absence and loss also permeate Unwrapping the Body, a 1979 book that accompanied an earlier art installation. Like Imogen, the book deals with the death of Paul’s daughter. Each piece in the book pairs a photograph with a page of text. The heavy printed text — some of it handwritten, some typeset — recalls the labelling of “Proper Names.” Yet here language is more explicitly concrete. This is especially so in “HEAD caput CUP,” in which most of the text is displayed sideways, stretching vertically down the page in a way that mimics the cord on which the colander is suspended. At first, it is tempting to view them as predominantly design elements: the different styles in which they are written adds to this, as does the minding of common words with medical vocabulary and words written in Greek characters (these Greek words are variations on the English words). These features distract from dictionary meaning. John McNulty, in an otherwise laudatory review of Like Love Poems, criticised this aspect of Paul’s “more experimental work,” describing such pieces as “typographic free-for-alls that push … words as far as possible towards being a purely visual medium.” Such pieces, he concludes, are “poor substitutes” for her paintings.[10]

The words in Unwrapping the Body, however, do have clear meaning. Imogen died, before her first birthday, of complications caused by a heart defect. Many of the words in Unwrapping the Body refer explicitly to the circulatory system (“VASA VASORUM” are networks of small blood vessels). Others evoke the medicalised or dissected body (“RIB,” “NEURON,” “GANGLION”), or to physical and/or emotional linkages and connections (“STRING,” “THREAD,” “BRAID”). Most starkly, there are words that read as direct references to the life of her small daughter (“LITTLE DISH”) and that daughter’s death: “CHEST,” “BOX CHEST,” “SACRIFICIAL BOWL.” There is, in these words and images, both extreme pain and extreme control; a poetry that far from rendering words, as McNulty puts it, “a purely visual medium,” imbues both image and text with deep layers of significance.

Such examples reveal a tension at the heart of Paul’s poetics. For all its open-endedness, her work has a centripetal tendency, spiraling in on itself as it explores lines of connection, shapes of movement, or spaces of absence. In part of a long piece titled “O,” short rhythmic lines descend towards a mystical central point:

an ear

to hear

a seed

to bed

and bleed

a word

to grow

hip

at the

centre

of the

rose

O [11]

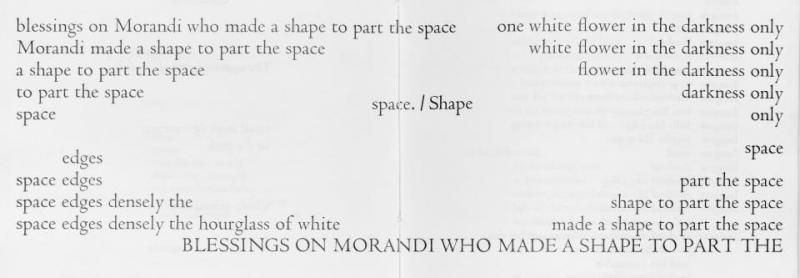

Of all her themes, this idea of the centre is the most revealing. Ironically, Paul’s is ultimately a poetics of convergence, yet her oeuvre is, from a reader’s perspective, scattered and largely inaccessible. Hall has described how, at the time of her death, Paul’s cupboards “were filled up to the roof with papers … ” There were poems on the backs of envelopes, down the margins of letters, the wedding guest-list beside the phone was itself a poem, in Joanna’s distinctive calligraphy.” The selected poems reproduces only a small part of this prolific output. As she explains in her introduction, Hall based her editing of Like Love Poems on a manuscript previously submitted by Paul to Victoria University Press. She did exclude some poems, including those where visual elements seemed to overtake textual.[12] Like Love Poems, then, does not include the double-page Morandi piece from Imogen, and the achingly emotive pages from Unwrapping the Body lie outside its purview.

Elsewhere in “O,” Paul presents another way of thinking about the centre:

O

eye

(look look

it’s in

my pictures

all lines

converge

at the centre

not the middle

but

just outside

the picture

here

O) [13]

The movement of Paul’s poems is a long arc inwards, but it is an arc towards a centrepoint forever out of reach. Her shapes map the body, the landscape, the ephemera of the everyday, but they also explore absence, negative space, loss. Now, a decade after its publication, Like Love Poems is itself out of print, the poems it contains falling back into the space from which they only recently emerged (though Google Books will let you see some of them, in limited preview). Hopefully, the future will see more of her work back in print, where it can continue to orbit a centre that lies perpetually beyond the edge of the page. — Cy Mathews

Joanna Margaret Paul's poetry, paintings, drawings, and films can be viewed online at the NZEPC, Art New Zealand, and Circuit.

1. Quoted by Hamish Dewe, “Parting Closure: Imogen and Unwrapping the Body,” New Zealand Electronic Poetry Centre, last modified August 25, 2005.

2. Andrew McNulty, “Lines of Beauty,” New Zealand Listener, June 24, 2006.

3. Jo-Marie Brown, “Rotorua Hot Pools Charged Over Artist's Death,” New Zealand Herald, December 1, 2003.

4. Catalogue essay to Wanganui Works: Resisting Foreclosure, Wanganui: Sarjeant Gallery, 1989, n.p.

5. Joanna Margaret Paul, Like Love Poems: Selected Poems, ed. Bernadette Hall (Wellington: Victoria UP, 2006), 34.

6. Introduction to Like Love Poems: Selected Poems, 11.

7. Like Love Poems, 68.

8. Ibid., 119.

9. Ibid., 119.

10. “Lines of Beauty.”

11. Like Love Poems, 96.

12. Introduction to Like Love Poems, 9.

13. Like Love Poems, 92.

Cracked mirrors