Twenty-six items from Special Collections (m)

Exhibit ‘M’: Urdu. (Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib, eighteen poems, nineteenth century)

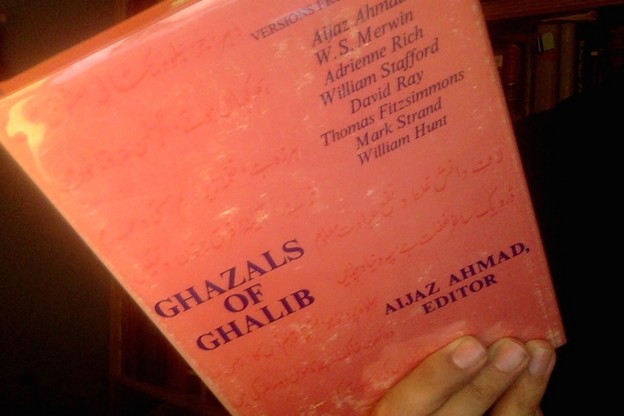

Bibliography: Ghazals of Ghalib: Versions from the Urdu by Aijaz Ahmad, W.S. Merwin, Adrienne Rich, William Stafford, David Ray, Thomas Fitzsimmons, Mark Strand, and William Hunt, ed. Aijaz Ahmad (Columbia University Press, 1971).

Comment: In 1969 The Hudson Review printed a sadle-stapled chapbook (price: 50¢) containing twenty pieces by Mirza Asadullah Khan Ghalib: ten translated by William Stafford, and ten translated by Adrienne Rich. These two American poets were, at the time, fifty-five and forty years old, respectively. They were not quite what we would today call "emerging poets"—but kinda. Neither had a Pulitzer. Each had five books out.

In 1969, Ghalib had only been dead a hundred years. Very soon it will have been 150, strange to say. The book pictured above was "in preparation" at the time of the chapbook, but it did not come out ’til 1971. The Stafford and Rich treatments are all present (though renumbered), and the editor, Aijaz Ahmad, also included the literal translations with which he had supplied his poets, along with the Urdu originals, and seventeen other Ghalib pieces. Also many, many translations by the five other poets listed on the cover. (The sharp-eyed may note the presence of the name David Ray on that list. He is the translator, a couple decades later, of the King Hala poems, Exhibit "D" in the present series.)

In 1994, Ghazals of Ghalib was reprinted by Oxford India Paperbacks. This book included a brief note from the editor, specially written for the reprint, which reads in part:

____________________

[ . . . ] The exercise was difficult; so, poets that we were, we chose to be playful. But a reprint, almost a quarter century later, of a work that so smacks of the impetuosities of youth involves for me a different, more dreary set of embarrassments. In the intervening years, my views have changed about everything that has a bearing on my own role in this book: the Urdu language and its poetics; the place of Ghalib in our literary and intellectual histories; my understanding of those histories as such; not to speak of poetry itself. Most things in the Introduction, and some in the apparatus I then provided for my collaborators, now strike me as wrong.

____________________

He also uses the expression "unforgivably young" in reference to his 1969 self. (All this is quite delightful.)

It remains to be noted that the pieces below in no case translate entire ghazals. Ahmad selected couplets entirely pursuant to his own taste. He cites, as precedent, Indian anthologies, which (he tells us) traditionally print only the "best" couplets of any given ghazal. This means that any "conversation" between the themes of adjacent couplets below may or may not be present in the originals; it's never certain the couplets were next to each other. Ahmad does not tell us where he has made cuts, nor how long the poems were before they were cut. I have a copy of Ghalib's Urdu divan right here, but it's not much help since I can't read Urdu. One thing I can say: not too many of these poems are five couplets long. I would say seven to ten couplets is typical.

Note: The Roman numerals on the poems are those present in the book, but I have arranged the pieces in the order they were in in the chapbook, where I first saw and fell in love with them. I trust this is sufficiently confusing. I have also silently omitted two poems that were in the chapbook.

Translations by Aijaz Ahmad & William Stafford

VI

Even God's Paradise as chanted by fanatics

merely decorates the path for us connoisseurs of ecstasy.

Reflected among spangles, you flare into a room

like a sunburst evaporating a globe of dew.

Oh, buried in what I say are shapes for explosion:

I farm a deep revolt, sparks like little seeds.

Thousands of strangled urges lurk in my silence;

I am a votive lamp no one ever lighted.

Ghalib! Images of death piled up everywhere,

that's what the world fastens around us.

VII

It wasn't my luck to achieve heavenly bliss.

No matter how long I lived, I'd never have made it.

Live on the great promise? Well, you can believe it;

I'd have died of joy had The Great One proved the Word!

This stone would have pulsed blood all over

if man's common suffering had really struck fire.

But who could ever find the True Mate, the Right One?

Could we sniff out soul-food, surely we'd do it.

These high, religious longings, Ghalib! These vaporings!

You'd seem religious if you didn't drink so much.

VIII

Here in the splendid court the great verses flow:

may such treasure tumble open for us always.

Night has arrived; again the stars tumble forth,

a stream rich as wealth from a temple.

Ignorant as I am, foreign to Beauty's mystery,

yet I could rejoice that the fair face begins to commune with me.

Why in this night do I find grief? Why the storm of remembered affliction?

Will the stars always avert their gaze? Choose others?

Exiled, how can I rejoice, forced here from home,

and even my letters torn open?

IX

Even at prayer, we bow in our own image;

if God didn't hold His door open, we'd never enter.

He has no image: outside, everywhere, so distinctly

Himself that even a mirror could not reflect Him.

Held between lips, lament burdens the heart; the drop

held to itself fails the river and is sucked into dust.

If you live aloof in the world's whole story,

the plot of your life drones on, a mere romance.

Either one enters the drift, part and whole as one,

or life's a mere game: Be, or be lost.

IV

No more campaigns. I have lost them all.

A doused light, I can't stand all the convivial fraud.

I can't find the truth. The world reflects

crooked, or the crystal ball distorts. The seer turns blind.

The brilliant and the real—I still know it's there,

but you never attain it by jiggling the senses.

So, it's dead in my breast, the zeal, the principle—

its only reward was the gleam while it vanished.

To you, my younger self: I still face the cruel game,

but this heart that beat hopeful can't take it any more.

XXVIII

You sensual novices, you are caught on a shuffleboard;

you stagger and pour away your lives.

Look at me, if your eyes can bring you a lesson;

listen to me, if your ears can take advice.

The bar-maid looks ravishing—she blots faith and reason;

the singer, she steals away your senses.

All around us, at night, we used to yearn for

those random bundles of flowers, all around us—

Liquid walk of the bar-maid, the zither's twang:

heaven for the eye, heaven for the ear.

But in the cold morning, abandoned by revelers—

no heaven, none of that old ardor.

A candle, ravaged for the carousing,

has guttered out; it too is silent, without any flame.

XXXVII

Of my thousand cravings, each one a career,

many I've done, but never enough.

You've heard of Adam driven weeping from Eden—

worse, leaving your place I felt you-forsaken.

Drink, for a spell, tarnished my name.

Even a king once found some truth in the cup.

Just when you think someone may feel for your plight,

it turns out he's worse off—even calloused, maybe.

For God's sake, preacher, don't snoop the wrong temple.

You might stumble on something better left neglected.

XXI

Dew on a flower—tears, or something:

hidden spots mark the heart of a cruel woman.

The dove is a clutch of ashes, nightingale a clench of color:

a cry in a scarred, burnt heart, to that, is nothing.

Fire doesn't do it; lust for fire does it.

The heart hurts for the spirit's fading.

To cry like Love's prisoner is forced by Love's prison:

hand under a stone, pinned there, faithful.

Sun that bathes our world! Hold us all here!

This time's great shadow estranges us all.

I

Only Love has brought to us the world:

Beauty finds itself, and we are found.

All time, all places, call—here, not here:

no mirror finds the truth but in itself.

To know—what do we know? To worship—

emptiness takes us into its craving.

Any trace, glimpse, whatever flickers—

that's all we have, known or not known.

Held by the word, targeted here in openness,

Earth receives the sky bent forever in greeting.

Translations by Aijaz Ahmad & Adrienne Rich

II

Nothing comes very easy to you, human creature—

least of all the skill to live humanely.

Time after time ahead of time, you fool,

standing in panic at the meeting-place.

The molecules of the mirror, if she appear,

longing to open like eyelids and take her in.

My body in the grave, scarred with its disappointments,

and yours, alive as the rainbow glistening through the orchard.

Killing me off she sobs: "I never meant to hurt you!"

Tears of repentance, wept three seconds too late.

III

Old, simple cravings! Again

we recall one who bewitched us.

Life could have run on the same.

Why did we call her to mind?

Again, my thoughts haunt your street.

I remember losing my wits there.

Desolation's own neighborhood.

In the desert, my own house rises.

I too, like the other boys,

once picked up a stone to cast

at the crazy lover Majnoon;

some foreboding stayed my hand.

XII

I'm neither the loosening of song nor the close-drawn tent of music;

I'm the sound, simply, of my own breaking.

You were meant to sit in the shade of your rippling hair;

I was made to look further, into a blacker tangle.

All my self-possession is self-delusion;

what violent effort, to maintain this nonchalance!

Now that you've come, let me touch you in greeting

as the forehead of the beggar touches the ground.

No wonder you came looking for me, you

who care for the grieving, and I the sound of grief.

XIII

All those meetings and partings!

Days, nights, months, years gone!

Falling in love takes time;

so enough of desiring and gazing.

It all took a certain force of vision

and the youth of the mind is over.

Shedding tears of blood is no game,

a strong heart, a steady nerve, are wanted.

I'm too old for an inner wildness, Ghalib,

when the violence of the world is all around me.

XV

Not all, only a few, return as the rose or the tulip;

What faces there must be still veiled by the dust!

The three stars, three Daughters, stayed veiled and secret by day;

what word did the darkness speak to bring them forth in their nakedness?

Sleep is his, and peace of mind, and the nights belong to him

across whose arms you spread the veils of your hair.

We are the single-minded; breaking the pattern is our way of life.

Whenever the races blurred they entered the stream of reality.

If Ghalib must go on shedding these tears, you who inhabit the world

will see these cities blotted into the wilderness.

XIV

Now the wings that rode the wind are torn by the wind;

their feathers dust of the desert, their force shrivelled to powder.

Anyone who can still hope is seeing visions.

The walls and doors of the tavern are blank with silence.

What, who is this, coming our way, with the face of an angel,

that the dust of the bare road is lost in a carpet of flowers?

I am ashamed of the destroying genius of my love;

this crumbling building contains nothing but my wish to have been a builder.

Today, Asad, our poems are just the pastime of empty hours;

clearly, our virtuosity has brought us nowhere.

XXII

Tulip or primrose, they have to speak in their colors.

Everyone answers the spring in his own dialect.

Poetry is really just a way of meeting poets;

and if they're good-looking woman, so much the better.

What kind of man gets stoned for fun?

Day, night, I need obliteration for my grief.

Facing the bottle, the blotted mind knows what it's facing;

facing the shrine the mind at prayer knows just as well.

The wine of the occasion changes its vintage,

but the great drinkers are always drunk on themselves.

XXIII

I suppose my love for you is a form of madness.

Why shouldn't that madness play like fire about your name?

Don't let a nullity fall between us:

if nothing else, we could become good haters.

Our time of awareness is a lightning-flash,

a blinding interval in which to know and suffer.

My method shall be acquiescence and a humble heart:

your method may be simply to ignore me.

Don't lose heart in this skirmish of love, Asad:

though you never meet, you can always dream of meeting.

XVIII

Come now: I want you: my only peace.

I've passed the age of fencing and teasing.

This life: a night of drinking and poetry.

Paradise: a long hangover.

Tears sting my eyes; I'm leaving

lest the other guests see my weakness.

I is another, the rose no rose this year;

without a meaning to perceive, what is perception?

Ghalib: no hangover will cure a man like you,

knowing as you do the aftertaste of all sweetness.

•

Twenty-six items from Special Collections