Trio of reports: Radar Productions, an evening of debate with some alleged members of the Invisible Committee, and Pierre Guyotat

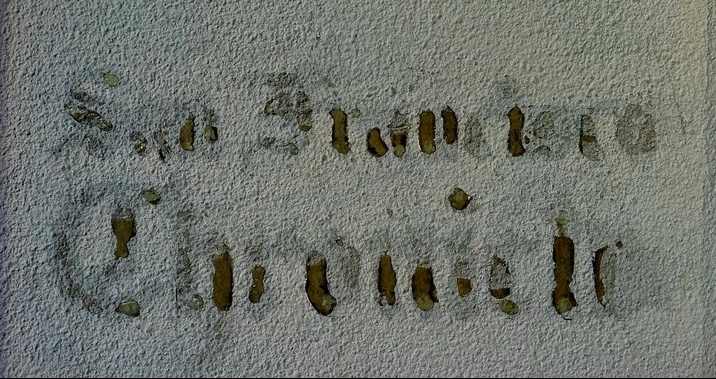

San Francisco Chronicle Building (exterior) / Intersection for the Arts (interior) photos by Del Ray Cross

I’m not sure if it’s the assignment I gave myself or what, but the last few weeks I’ve found myself in San Francisco way more often than usual. Often enough that I keep buying and misplacing BART tickets, finding them in the laundry later. The train thing is no small deal: I was unable to ride BART for several years after my father’s death, caught in the grip of phobias perfectly expressed by the vulnerability of the transbay tube, phobias which in turn helped crystallize my hatred of BART, for reasons too many to list here but including the lack of public oversight re: BART cops, the way the train is so clearly designed to move money around—commuters to the financial district, bodies to airlines—rather than serve the neighborhoods it moves through. The communities it destroyed when it was built. OK. Stopping myself. Getting it together. Suffice to say: I’ve been riding the train. And going to more readings in San Francisco.

Not to get prescriptive about it, but I’d recommend the assignment I assigned myself to anyone. It’s been invigorating, especially the last five days, crammed as they were with Radar on Thursday, an evening of debate with some alleged members of the Invisible Committee on Saturday, and then on Monday, Pierre Guyotat at City Lights. In the back of my mind all the things I’ve missed, including the inauguration of of a new talk series at Brian Ang’s house. Saturday night in particular was a total mess; attending the evening of debate meant missing Jessica Haggedorn at Intersection for the Arts and Bhanu Kapil and David Buuck at Condensery, which otherwise wild horses couldn’t etc. And then going to work has meant failing to write some things down in rhythm with my thinking and response to everything I’ve heard and encountered in the last five days. While I’ve been calling on the patron saints of brevity here, it’s been to no avail, at least not today. Everything continues in its state of being crammed against everything else in my brain and I don’t know how to untangle it.

In the Department of one’s calendar inexplicably working in interesting narrative relation to one’s intellectual projects, the Radar reading last Thursday happened to be the first public event held at Intersection for the Art’s new location. I’ve been thinking about art spaces in Oakland and wish I knew more about San Francisco so that I better understood what this move means, the conversations and probably arguments around it. Some part of me, the profound creature of habit, suggested to Del Ray Cross that we meet for dinner beforehand in the Mission, near the old location. Like they’d officially moved, but would still be holding literary programming in the space on Valencia, why would I think that? We took a taxi to the Chronicle building after realizing this mistake. And there it was, the new Intersection for the Arts. There are about a million things one could say about the space. It’s very open, and modular, with offices around the perimeter and a sort of living room section as you walk in. Several rows of seating comprised of ergonomic office chairs. I was somewhat obsessed with these chairs, which were super comfortable, armchairs on wheels. I kept thinking they must be easy to put away. But office chairs don’t fold up. Maybe they don’t get put away? I liked how these chairs allowed for a lot of individual room if one wanted or needed it. Also I felt like a pilot in my chair. Of a video game.

I’d never attended a Radar reading before, and it was pretty great. A variety show in the best sense, the lineup included photographer Monty Suwannukul, who told a story about some images as he projected them, two stories actually, all about nature, zoos, mall culture, cuteness and objectification, a reading from Sara Bierman’s lesbian farce Madhouse, recently performed at the College of Marin where the administration required warning signs be put on promotional posters for the play, a short story by Philip Huang from his collection A Pornography of Grief, Lucy Corin’s lecture on Godzilla and the Smog Monster, and readings by Trinie Dalton which I can only describe as, can I describe them? Photorealist monologues? Prose persona poems in a tonal register of self- or identity-deprecation? It’s difficult to venture into description here because with the exception of Lucy Corin, whose lecture was fabulously jokey about lectures, beginning with a bulleted list of reasons why we could tell this would be a lecture, including the powerpoint blackboard format and “I know almost nothing about this” and “I’m wearing a blazer” (or was going to, but had left it draped on the back of her ergonomic office chair) I wasn’t familiar with any of these writers and artists before Thursday. Which is kind of an amazing audience position to be in I remembered.

Monty Suwannukul, audience in ergonomic office chairs. photo by Del Ray Cross

The other terrific thing about this reading, HOT PROBS, fell roughly at the spot where one might otherwise expect an intermission. This installment of HOT PROBS featured Ben McCoy and two performers dressed as, what is the name for an assistant to the oracle? Like that, draped in mauve and carrying burning sage, one on either side guiding Ben to stage, the upper half of his face covered by a heavy lace veil. Michelle Tea crouched behind the podium and called out questions written down by audience members before the reading, such as “are there any safe antibiotics?” and “I would like to be an artist but the city is too expensive. What can I do?” Ben McCoy intoned answers while the oracle assistants waved their arms, swooning tentacles, and made sounds somewhere between purr and moan. HOT PROBS was like a really great amuse bouche of poets theater, probably I mean performance, and whatever the word is for an amuse bouche that falls between courses instead of at the beginning of the meal.

Hot Probs wth Ben McCoy, photo by Del Ray Cross

The other architectural thing I kept obsessing on during this reading was Campo Santo, and how in the world are they going to produce theater in the new space? Will they forego a backdrop? Theater in the round, with ergonomic office chairs? Maybe they will create tableaux vivant in the perimeter offices, and audience will go from door to door to peer in. Obviously they have something in mind and I will be intensely curious to see their upcoming show. I talked about this question later with my friend Natalia Vigil, who I haven’t seen in over a year, a surprising treat, and we caught up on news of our mutual friend, poet Felicia Martinez, who recently moved to New York, how we missed her, and I talked to Charity Coleman who is also moving to New York, I will miss her, we talked about the challenges and excitement of moving to New York, and I waved hello to Ariel Goldberg, and chatted with Margaret Tedesco on the sidewalk before walking to the train. Margaret and I talked about east bay people not making it to San Francisco for events, and vice versa, or the difficulty of that commute on top of all one’s other commutes, and how I’ve somehow never made it to her shows at 2nd Floor Projects. (East bay folks, take note: Tedesco has added gallery hours on Wednesday exactly due to this east-west bay commute challenge. The edition for the next 2nd Floor Projects show will be by Trinie Dalton. Also everybody everywhere take note: BOMB is reprinting 2nd Floor Projects editions online. OK, one more thing for your calendars: Rhodessa Jones will be giving a presentation at the next Radar on how to look good in a cheap piece of clothing. And! Renee Gladman is reading on June 1.)

Coming back around here to thinking about one of those questions the oracle answered. The city is too expensive. How to be an artist. Jasper Bernes recent post on the SF Moma blog. Margaret’s project in her apartment. In Michelle Tea’s announcements at the beginning of the reading last Thursday, she reminded everyone that Radar roves, sometimes to the library, sometimes to the Luggage Store, and let her know if you have a space with a lot of room, maybe it will rove to your house.

The debate with some alleged members of the Invisible Committee happened at Station 40, and ever since I’ve been marvelling how it is that “a collectively run, anticapitalist community events space by and for radicals, anarchists, heretics, and many others who seek an egalitarian world without hierarchy” is able to maintain a fairly large public event space in the heart of astonishingly high rent, near the corner of 16th and Mission. It can't be easy. (Thinking this partly through ATA’s ongoing financial challenges, although again I am woefully under-educated about San Francisco, beyond the obvious and intense gentrification of the Mission over the last 20 years.)

Station 40 has a kind of ATA feel but more so, it’s a place where you can see films and lectures but also attend salons and potlucks. People live there I think. I arrived early, with Brandon Brown, Cynthia Sailers, and Lauren Levin, early because we were worried it would be packed and/or start on time. It was the end of a long and beautiful day, in which the sun was out and people were aggressively selling bubble machines on the street. A day of leisurely and decadent lunch. A day that began with a ladies radical clothing swap organized by poets Sara Larsen and Lindsey Boldt (remember how I said that if bay area poetry communities were the YMCA there would be no women’s locker room? I stand, happily, corrected.)

It’s good we arrived early because seats did fill up quickly, to standing room only capacity. The crowd was generally pretty young. Lots of people were eating burritos. I saw Tim Kreiner in the room, heard Chris Daniels speak from the back, ran into Anne Lesley Selcer on the street afterwards. The event began with an announcement that police aren’t allowed in Station 40, and neither is sketchy behavior. And that people should be smart about the kind of questions they ask in this kind of space, an admonition our little group puzzled over later. Throughout the night there were various kinds of questions asked in various tenors, and arguments and contentious moments so I’m not sure what kind of question would be not-smart. As I type this I am having a doh moment that perhaps a not-smart question might involve specifics regarding acts of sabotage, might fall into the more explicit vein of how-to.

It was a relief to be in a space where questions did in fact sometimes run towards the largest sense of how-to, as in how best to organize “past the catastrophe,” as in the total transformation of human organization, as in the big questions stated in the 2009 preface to The Coming Insurrection, which mostly got reiterated over the course of the evening: “How does a situation of generalized rioting become an insurrectionary situation? What to do once the streets have been taken, once the police have been soundly defeated there? ... What is the practical meaning of deposing power locally? How do we decide? How do we subsist? How do we find each other?”

The night went like this: a group of people, the alleged members, sat down up front. Four men and one woman. They were joined by moderators Caitlin Manning and Japser Bernes who gave a brief intro, and then the alleged member most comfortable speaking in English talked for a while. There is too too much to report on here but also I didn’t take great notes, there were no microphones, and I was seriously wishing for an interpreter / translator on the scene, especially once the questions started. That is, mea culpa in advance for anything I get wrong here.

The alleged member who did almost all the talking (sometimes leaning over to discuss a question with another member) was pretty charming. There was a great moment when he was citing a historian, whose name I didn’t catch/know, and said something like “it’s not important that you know who that is.” He was jokey and smiley. And seemed to be aiming in his speech towards accessibility to many people, not just experts or the initiated. The idea he cited in that moment circulated around three figures, or actions, the three legs of a tripod necessary to any revolutionary movement/group/individual: the monk, the warrior and the farmer. Thinking, fighting and eating. And how if the tripod leans too heavily in any one direction, the movement tips and becomes something else, something static or dead. Later, during questions from the audience, I was struck by a seeming schism between these modes and speakers in the room. Such that there were some earnest questions about organizing in rural versus urban spaces, about local economies (to which the alleged member responded, again, that the Invisible Committee are very particular about the word “economy,” and don’t believe in? or use? this word, because it’s a word for power relations. That economy doesn’t exist.) And there were some nearly incomprehensible theoretical questions. And there were some people requesting that questions be more to the point. And there was at least one very angry question about the efficacy of localized / small protest and riots in the face of an enormous tentacled sprawling global capitalism demonstrably resistant to such protest. The moderators had also prepared some questions in advance, which the alleged members had time to read and think about beforehand. Caitlin Manning asked a question about how the invisible committee squared (that is probably not the right word) their politics of withdrawl and (I forget the second word she used) with their rejection of the milieu, the scene. Jasper Bernes asked a question about the group’s position on blocking flows in the metropolis until things fall apart, and how “an archipelago of communes” might not in fact be sufficient to meet what are sure to be staggering needs for food, water and services after things fall more apart, and so why not other methods such as seizing the means of production?

I was struck by several things I am hard pressed to connect here. The Invisible Committee’s emphasis on language and the need for any transformation to include these materials. How the alleged member kept using the word “amputated.” The emphasis on all previous modes of resistance as insufficient to the current moment. The sense of the present, of what is at hand, now. The repetition again and again that like the economy, the self does not exist. That the self is profoundly composed of flows and affects moving through the idea of an I. That the dichotomy between the individual and the group is basically a false one.

I kept thinking about this repeated insistence on the individual as an idea, and not real, during Pierre Guyotat’s reading on Monday night at City Lights. How Coma is a book that opens with a crisis around the individual, a book that begins: “The following narrative I have carried within me ever since, surfacing from a crisis that had led me to the brink of death, in the spring of 1982, I forced myself to speak again in my own name. At the time I felt disgust—it was really the only feeling I could summon in preparing and pronouncing the word “I” with my throat and mouth, since I hadn’t recovered the totality of its attributes—“

Guyotat opened by reading from last section of Coma in French, and then Noura Wedell, the book’s translator, read from the same selection in English. As we were about to move into a Q&A, Wedell mentioned that they had discussed the idea of Guyotat reading a section from Eden Eden Eden in English, to which the crowd responded with a resounding and excited yes. Guyotat didn’t have the book with him at the front of the room, and someone was going to procure it from an office when Kevin Killian pulled out his copy for Guyotat to read (big surge of affection for Kevin here.) Thereafter followed the Q&A, during which I was reminded how the embodied presence of translation changes a group’s dynamics, builds a group, and a group conversation, that might not form itself otherwise. How live translation necessitates multiple repetitions, people chiming in to clarify, or ask a question about the question, the whole thing simultaneously foregrounding and attending to the multiple difficulties of language, communication, perception.

Pierre Guyotat and Noura Wedell, Juliana's hands and phone

Some of the most interesting moments during the long conversation that followed came in response to Dodie Bellamy’s question about the intersection of memoir/fiction in Coma (Guyotat: “It’s my life. It’s not a novel. It’s my life.”) and how the book was commissioned by its publisher (Dodie: “But they didn’t commission the experience?”) Big surge of affection for Dodie here. The increasing difficulty through which Guyotat writes, how all his nonfiction works are dictated to another person, how in producing autobiographical or essay writing he requires the presence of others, is even, he used the word “constrained" to dictate certain works. He talked about feeling less sure of Coma, whereas Eden Eden Eden he “wanted and invented,” and how scary it is to create, more and more scary. People kept asking about his influences, or his thoughts on other writers (Beckett, Burroughs—of the latter he said “Yes of course like everyone”) and he talked about having not read any contemporary writing when he wrote Eden Eden Eden, how he still hasn’t read Bataille or Freud. He talked about how a politics must be physical, must take a risk, and how he doesn’t think much of political work that is only intellectual, is only ideas, and not physical. He talked about how the role of the intellectual or artist should be to make others aware that they can think and act. That he wants his work to inspire people to know that they think. He was asked about his dreams, if he dreams much more today (yes) and in color (yes.) He said his dreams are more like real life now, that reality is “almost there.” Tom Comitta asked a great question about risk, what is at risk in a book? And I wrote down part of the answer in all caps, RISK IS SOCIAL. Guyotat talked about one’s name being attached to a text, about not having a pseudonym, and he told a story about living in his van for ten years, in villages, on the outskirts, and how he had this fear that if something happened, if a crime was committed, he could be charged easily—just open any of his books and make some assumptions. His name is there.

On our way to a late dinner after the reading, I suddenly realized how exhausted I was, and bid my friends goodnight. Striding through the not-nearly-so-windy-as-last-week streets of the financial district, dressed in clothes obtained almost entirely at the ladies radical clothing swap (crisp white skirt, yellow print button-up shirt, red espadrille heels tied at the ankle) I became increasingly anxious about taking the train home, or rather, increasingly anxious about what to do when I arrived on the other side of the bay. I never walk home by myself from the station after dark, despite its being only a few blocks away from where I live, due primarily to several long unlit stretches, blocks sometimes devoid of other people. The landscape can feel, to use a jokey description coined by Anne Boyer, Dana Ward, Alex Savage and myself while walking along a lonesome bike path on the Missouri River just before we found / manifested two abandoned kittens, a little rape-y at night. Usually I park the car at the station and drive those few blocks home in acute shame over my privilege, cowardice, and resource hogging, but my guy-husband-person-partner needed the car on Monday night, his rehearsal was going to run late, and I’d gotten a ride in with Juliana Spahr and David Buuck who were staying in the city for dinner.

And so, as the train went under the water and my ears popped at the change in pressure, the delight I’d felt all day at wearing clothes which brought my radical lady friends to mind turned slowly towards berating myself for being dressed so inappropriately, and the perverse pleasure I generally take in being a smart and serious person shod in the easily dismissable costume of a high femme gave way to feeling like a total idiot. If I was going to walk home in the dark by myself I should have at least worn jeans and boots. But there I was, in the nearly balmy night, having arrived safely thus far, having not drowned in the transbay tube during an 8.0 on the Hayward fault, my mind alive and full of ideas crammed altogether. I resolved myself and clomped home in the inappropriate red espadrilles at high speed, moving from streetlight to streetlight, ignoring that mild verbal harassment so often directed at any walking person who for whatever reason signals the shape “woman." Whatever. I felt grateful right then for the sexist speech that signaled the presence of others, grateful not to be on the street alone in the dark, which is always scarier and arguably more dangerous. I turned the corner and walked up the middle of my street, avoiding the sketchy sidewalk, delighted all over again, this time by the many windows and front doors open in the first warm evening of what is almost summer.

The more territories, the more circulation