Trauma, tenderness, and the archive

Sydney L. Iaukea, Sarith Peou, Adam Aitken, and the emotional archive

It was one of those days when everything random converged. The evening before, our friend who devoted a long career working with youth at risk talked to us about another friend, a Khmer Rouge survivor, who has spoken to several of my classes. The first time he told his story, he traumatized my freshmen by telling them about a woman bludgeoned to death before her colleagues for asking for more food. He finished the story with a laugh. My students couldn't get over his laugh. It assumed more importance to them, it seemed, than the story itself. “He shouldn't have laughed,” more than one told me. That day things converged, call it last Thursday, I awakened to an on-line citation of a memory card of my own, plucked at random by Joseph Harrington from my new book, based on a story told to me by a man who works as a prison psychologist, whose mother was in the same Alzheimer's home as mine. “He tells me about a [Cambodian] prisoner, 72 years old, stuffed inside a suicide shirt, who screams in Khmer that someone is beheading him.” And at noon, I attended a talk at the Biography Center at my university by Sydney L. Iaukea, whose new book is The Queen and I: A Story of Dispossessions and Reconnections in Hawai`i. Iaukea is a political scientist writing about the trauma of Hawaiian history, the effects of those traumas on extended families like her own. While Iaukea spoke about what she had learned about her family, her family's selling of their land, her great-grandfather's relationship to the last Hawaiian Queen, Lili`uokalani, what impressed me most, in the context of teaching a course in documentary poetry, was her discussion of the archive in emotional terms. My students have discovered that working with documentation does not cut the emotional charge of their projects, but compels it. As Iaukea writes, "To recognize the loss of land as the loss of self is an enormous and very personal endeavor, one that makes historical occurrences very real." The archive offered her a renewed sense of these losses, some of which had been kept secret from her growing up.

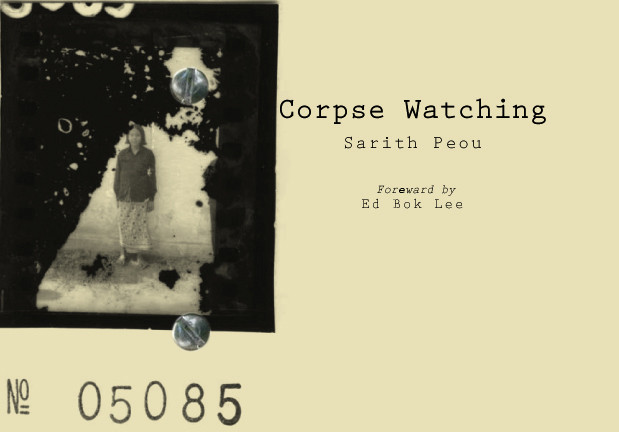

In 2007, Tinfish Press published the work of a Cambodian holocaust survivor now serving two life terms in prison in Minnesota for killing two other refugees from the Khmer Rouge. The book is titled Corpse Watching, after one of the poems. The book was sent to me by Ed Bok Lee, who had worked with the author, Sarith Peou, in the prison. Peou's second-language English is straightforward, documentary, the content all the more stark for it. Our designer for the project, Lian Lederman, found out about the archives of photographs of people killed at Tuol Sleng, a school converted into a death factory, and acquired copies of photographs from the Documentation Center of Cambodia in Phnom Penh. It bears saying that Lederman, then an MFA student in art, is Israeli. The chapbook she designed has two sections. Its covers are heavy manila paper, like folders where such photographs would have been kept. On the larger right side of the two screws that hold the book together are Peou's poems, printed in typewriter font; on the left side, making a kind of flip book, are photographs of some of the Khmer Rouge's victims, taken just before they were killed. Lederman talked in one of my classes, one she attended with our Cambodian frirend, Hongly Khuy, about how difficult it was to cull the photographs. She felt that she was consigning the subjects of those photographs she didn't choose to a second oblivion. The archive was drawing her into the horror, not as a passive (if distressed) witness, but as something of a participant (albeit delayed, and less deadly). That many of the victims whose photos are included are young boys and men, some of whom resemble my son (who was born in Cambodia), involves me in that archive, as well. This is family, however extended, attenuated. My son may have come to my husband and me because of that awful time. Cambodia's self-destruction was more than aided by the USA's "secret bombing" in 1960-1970. (That campaign of carpet bombing was performed under the awful name, "Menu.") In 'Scars,” Peou writes that he and his peers named their wounds after bomb craters created by different US warplanes, the T-28, the F-111, and the infamous carpet bomber: “My B-52 didn't heal,” he writes, “until the Khmer Rouge fell, / When we had enough food to eat.”

In “My Sister Ranchana,” Peou writes about a sister he left behind in Cambodia. The Khmer Rouge had taken her to a “work farm” at age seven. Twenty years after their regime fell, she suffers severe PTSD, panic, diarrhea, hospitalizations. But the poem does not stay with Ranchana, rather moves to Mee, “the cadre who mistreated Ranchana.” The speaker in the poem names his dog Mee, abuses the dog, eventually eats the dog. Then:

A few months later

Mee died from delivery complications.

I thought my curse had worked.

Now I feel guilty for misplacing my anger on my poor dog.

The book is full of pain, for which there is no relief. The full manuscript was at least three times longer than the Tinfish Press chapbook, and Sarith Peou has also written a huge memoir, which is in manuscript.

If Peou's writing cannot heal him, then it can traumatize its reader into awareness. His archive, and the archive of photographs, draw in the Israeli designer, the American adoptive mother, and anyone who reads the book. The awful Cambodian decade of the 1970s and its aftermath also drew in the Australian poet, Adam Aitken, who lived with his wife for a year in Cambodia. In “Forest Wat, Cambodia,” he writes, “Who knows if suffering's inquiry leads you anywhere / but back to suffering?” (Eighth Habitation, 86). He stands in a train station, considering the landscape itself as aftermath to genocide: “The tracks were ripped out years ago / by lads who knew more about suffering than we ever will. No end to it.” He notes that history cannot stop itself, even in the face of such trauma.

And yet, you're right . . . the children

still wave here, though hardly a soul over forty,

and those who remember can't quite recall

the historic meaning of their lives, or

how their names are spelt: just

to have come this far, along the road,

just this sack of green leaves, this hammock in the trees. (86)

The only access he has to someone else's pain is to witness their forgetting. (I also remember being taken aback in 2000 when I saw a man on a motor scooter in Siem Riep with gray hair.) Adam Aitken makes his own pilgrimage to Tuol Sleng (S21) to try to recall what happened. He wonders what it means for him to take photos, read the archive:

How to come away from it,

to photograph it, how long to stay there and stare

at the spattered tiles and the ripped out wiring.

To wonder what endless days

reading an archive of ten thousand ‘confessions’

does for the eyes; I’m sick of questions

no-one wants to answer. (105)

At the end of the poem, he compares himself, a poet, with the man who took down the records of those killed in this awful awful place. Aitken’s writing is always limpid, but this conclusion chills to the bone:

I too have to write, wondering where I am

on the chain-link of paranoia

connecting a tyrant to a farmer's son

who was handy with a shovel;

someone like the accountant across the corridor

doing the company's credit/debit sheet —

the guy with all the stories, who

knew how to file, the one who said

he’d done his job protecting his nation

with a few blunt instruments

a fountain pen, and a beautiful signature. (106)

In Peou’s poem, “The Unfitted,” a Khmer Rouge boy at a Traditional Medicine Center is given a pen and paper. He exclaims that the boy draws so skillfully, even as he draws the engines of death, bodies of the dead. The connection between art and genocide is what Adam Aitken calls a “chain-link of paranoia.” It may not ease suffering, because as Aharon Appelfeld writes in The Story of a Life, “Words are powerless when confronted by catastrophe; they're pitiable, wretched, and easily distorted. Even ancient prayers are powerful in the face of disaster.” But the chains at least have links. Appelfeld: “I learned how to respect human weakness and how to love it, for weakness is our essence and our humanity.” It is as record of this weakness that the archive emerges not simply as a place to leave our documents, but also to grieve over them. We may not fully remember ourselves or our histories, but we will see the pieces better for it.

Experimental poetries in the Pacific / editing Tinfish Press