A same time speed

Moyra Davey's 'The Problem of Reading'

Recently, on a frigid winter day, she found herself in her studio surrounded by layers of books and papers. From this mass of paper strewn all over the sunlit floor, she began to conjure up an image of it all coming together, the parts knitting themselves into a web or net capable of holding her in a sort of blissful suspension.

At the end of Moyra Davey’s The Problem of Reading, she changes from the first person to the third person, to talk about herself, her own habit and narrative of reading. The move from essay to narrative struck me. How does this work in a photograph, in which you can’t change pronoun but you can have both essay and narrative?

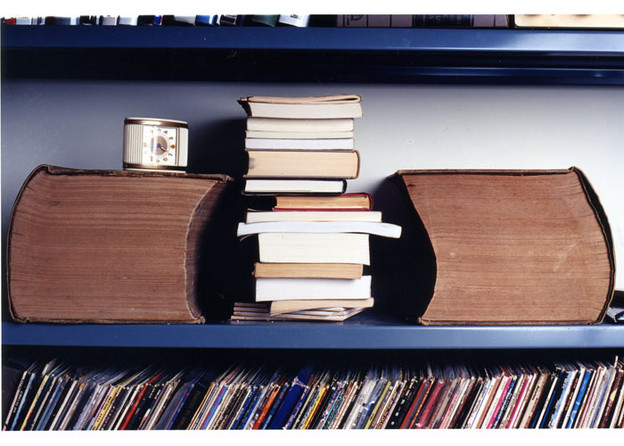

In the first image of the book, two walls meet at a right angle and books are on tall, long metal shelves. A florescent light hangs overhead but it is off. Natural light pours in from a window we cannot see. There is no pronoun in these images of books; or it’s the third person and first person at the same time. Davey’s images progressively move in on the shelves, and then in on books in a way where it's the clutter on the shelf, not just the book. The subject becomes dust or the way the books lean or even little bookmarks of scraps that look ripped out from books. The last image shows the library from the first image disassembled, bare, a seeming match for the excerpt above. As if the books all entered an invisible subject. The variations on how to look at reading materials keeps the adventure wide, how you can enter.

Davey’s “problem of reading” is not the problem of close reading but rather the problem of the habit of reading. In particular reading choices. Davey’s essay is a progression of thought and collected research through that progression. The essay is embedded in a volume in which the text takes turns with Davey’s photographs as well as photographs by JoAnn Verburg and James Welling. Verburg’s subjects are overshadowed by the newspaper in their hands and Welling’s are close-ups of intimate scripty handwritings with leaves and feathers as their flattened companions. The photographs are all “about” reading, but what do they do in terms of the progression of the essay, how they more than lend a claustrophobic atmosphere, remains suspended.

I’m reading Damnation by Janice Lee, an ekphrasis of Béla Tarr’s films. It is a book that among other things addresses time and cinema, or image, against the time of narrative. Both of these writers pose the question of correspondence between the time of writing and the time of image. Take for example the case mentioned above, in which Davey switches from talking generally about the subject to talking about herself as the subject invoking herself by using a “she” pronoun. We know that the position of interpretation has shifted. You cannot make a pronoun of a character change in a photograph as you can in a progression of sentences. You can’t represent the writing in the photograph or the photograph in the writing but what Davey does do in both is produce a corresponding or same time, speed, and affect. Deeply contemplative. Sort of slow. At least steady. There is a trust to the next footfall, like a walking meditation. It’s a modernist time. Virginia Woolf. Calvino. I have no patience for Harold Bloom and I was interested in Davey’s patience with him, the crotchety adult with mean requirements versus pleasure, play, politics.

Additionally in both the photographs and the essay, Davey is tracking a sense that proliferation exceeds the measure of her (attempts at) steadiness, progression, control. At the limit between her work and the place of its making is a feeling of out-of-controlness, i.e. the ever-present horror: how much there is to read. Her work pronounces (confesses?) with humble honesty while indulging in the narrative of process. Photographs serve as the intermediary. Holding space, keeping horror at bay.

Inside The Problem of Reading lies a critique of how in our present, everything is planned, announced. There is intentionality in doing a project and then there is the unplanned present of something you cannot predict. Davey both maintains a Kafka-esque, absolute enrapture with a text, while muddied by the curiosity into any possibility, what she might miss, what may not have place. The contradiction of mastery and childlikeness.

The essay builds up to the question of how the writer and reader are in a welcome conflict and how that is distinct from when these two tandem forces work symbiotically. Time is kindling this writer/reader conflict. Davey writes: "...I don’t mean to suggest that reading and writing are one and the same—writing is infinitely harder." There is a tempting conflation between reading and writing at various stages of defining these forces; the conflation is perhaps a stand in for childlike play, a form of escape by way of how productive a sometimes contradiction can be.

Reading as a writer necessitates the risk of possibility: maybe writing will happen and maybe it won’t. Either way you’re screwed. When I finally write something I have to cut myself off from whatever reading was necessary to write it. The reading I set out to do before the writing is always incomplete and perhaps that is why reading occupies both spaces, the intentional reading space and the unintentional writing space.

The reading material always sneaks back in, or stares at you on the desk, the shelf. Calls to mind Julie Patton who in her apartment reverses all the spines of her books because she is overwhelmed by the clamoring and competing voices of spine faces.

Davey has a series of pictures of people writing in many different ways on the subway, which she has turned in to the posters she mails to friends and family that are then hung simply on a gallery wall with tacks.

I accept that as writer I am reader. Conversely, I take pictures to document my life; I don’t think of myself as a photographer.

I am amazed that you will take any pictures without anxiety.

But as a writer it would be impossible to me to read without anxiety.

Social reading