Reading Vancouver from abroad

Departing slightly from the topic of Vancouver poems by Vancouver poets to include Vancouver poems by non-Vancouver poets, this commentary considers work by French Modernist poet Guillaume Apollinaire and Jacqueline Suskin, a contemporary Los Angeles poet-entrepenuer who sells poems at the Hollywood Farmers Market. Apollinaire’s poem “Windows,” from Calligrammes, a posthumously published collection of poetry, was written a century ago while Suskin's poem “Vancouver BC” was a few days ago, last Sunday.

The following excerpt from “Windows” registers the phemonenom of urbanization and the precedence of the city in the early 20th century:

Towers

Towers are the streets

Well

Wells are the squares

Wells

Hollow tree sheltering vagabond mulattoes

The Chabins sing melancholy songs

To brown Chabines

And the wa-wa wild goose honks to the north

Where raccoon hunters

Scrape the fur skins

Glittering diamond

Vancouver

Where the train white with snow and lights flashing though the dark runs away from winter

Oh Paris

From red to green all the yellow dies

Paris Vancouver Hyéres Maintenon New York and the Antilles

The window opens like an orange

The lovely fruit of light

Apollinaire’s juxtaposition of the (colonized) Antilles to (colonized and settled) Vancouver to (imperial) Paris creates a sense of space-time compression in the poem that represents real world changes to mobility engendered by speedy methods of transport like trains, while the line composed of a list of cities situates Vancouver within a modern global context. The poet summons images of two important enterprises in the settlement and expansion of Vancouver: the fur trade and the railway–railways built by Chinese labourers sometimes identified on payroll records only as chink #1 or chink #2; railways used to transport weapons, people, and goods across the vast Indigenous territories known as North America; railways that no longer see the same levels of use in postindustrial North America but are still used to transport natural resources and commodities as well as support the tourism economy.

“Windows” and the other texts that begin Apollinaire’s Calligrammes were written in December 1912 and early 1913. In 1912 the City of Vancouver was twenty-six years old and had just superceded New Westminster in population. A Vancouver alderman gave a speech on unemployment at Oppenheimer Park, the same park where today a tent city continues to hold ground in protest of homelessness; the speech was disrupted by the addressed laborers whose dissent was quickly suppressed by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. The Canadian Pacific Railway Station opened at 1 West Cordova Street on Vancouver's Burrand Inlet waterfront, which now operates as a transit terminus for the city’s Skytrain, Seabus, and the West Coast Express, a commuter train to the suburbs. Let us now take Apollinaire’s train to Los Angeles.

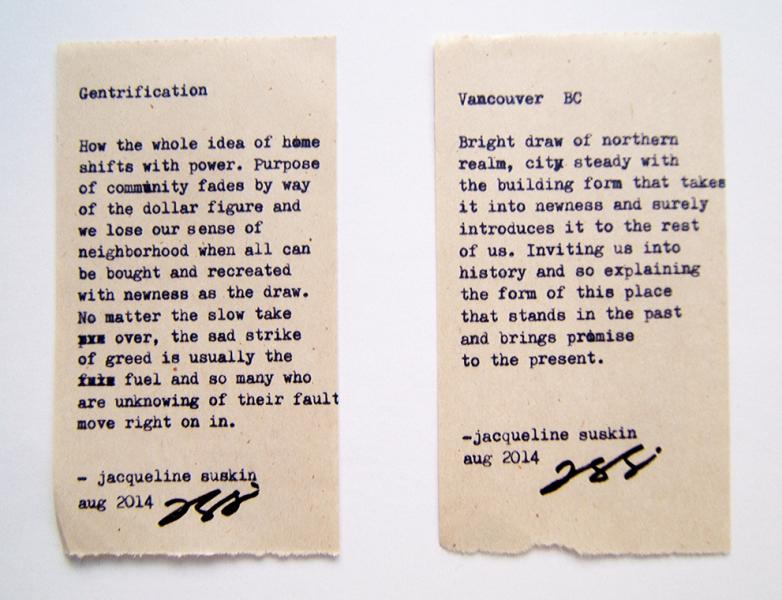

Suskin is owner of the Poem Store, which, according to the poet's website is “a performance-business-poetry piece that consists of composing custom poetry on a manual typewriter, in exchange for a donation. Your subject, your price.” Her moveable store—the phrase that comes to mind is ‘pop-up shop’—comprised of chair and vintage Hermes typewriter, often appears at the Hollywood Farmers Market. Curious about the idea of written-on-the-spot-for-money poems, I visit the market to buy one on gentrification in Vancouver, a research topic of mine and other Vancouver poets. The poet says she cannot write on gentrification in Vancouver not knowing the specific context, but can write on gentrification so I buy 2 poems, one gentrification, then another on Vancouver. Suskin types her poems on pulpy slips of paper about 2 inches wide and 4 inches long; they look like receipts.

Suskin's poem “Gentrification” generously excuses new higher-income residents—the “so many who / are unknowing of their fault / move right on in”—crediting them with an ignorance of their displacement of low-income and poor people. I lack this generosity and question the sense of entitlement emanating from these new residents in my own neighbourhood, Gastown, one of Vancouver’s oldest and most aggressively “redeveloped” areas. This month's Beachhead, a Venice Beach community newspaper, features Bruce Meade's article on gentrification in the area, “Will Venice Become a City of Strangers?”. Meade discusses the loss of affordable housing in an already pricey rental market as landlords convert long-term rental units into profitable short-term rental units (less than 30 days). He argues that online brokers of short-term rentals like AirBnB facilitate the reduction of the supply of long-term rental spaces where people can live, while the Los Angeles Short Term Rental Alliance, a recently-formed groups of landlords, wants to ensure that Venice doesn’t follow the lead of other cities like New York and New Orleans that have banned short-term rentals. While the pace and form of gentrification is multiple and complex, it is clear that it results in a loss of low-income housing stock. I cannot speak to the numbers of homelessness people in Los Angeles except to say I saw more people sleeping in the open air or in tents in Venice this year than the last. The [b]“right draw” of the city described in Suskin's “Vancouver BC” appears to be drawing the same type of people able to rent or buy property in Venice's exorbitant real–estate market, the gentry.

Unceded west coast city: Vancouver