Downtown Eastside poets: Bud Osborn

Bud Osborn was a poet and social justice activist much beloved in the Downtown Eastside. His death in May this year is loss to the community. Osborn was a founding member of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), a collective advocating for harm reduction policies in the City. Harm reduction views addiction as a medical issue, with users having rights to access health care such as safe injection sites. Begun in 1997 in response to escalating pandemic and overdose rates, VANDU’s work on harm reduction is globally recognized, and they were piviotal in the opening of Insite in 2003, North America’s first and only legalized safe injection site, located on the north side of the 100-block of East Hastings Street.

Hundred Block Rock (Arsenal Pulp Press, 1999), Osborn’s fifth poetry book, is a powerful collection of poems about the Downtown Eastside. The title refers to the geographic centre of the neighbourhood. In the dominant media, the 100-block of East Hastings at Main is frequently depicted as the “epicenter” or “ground zero” in Vancouver’s “notorious” Downtown Eastside. To the hundreds of low-income people who everyday use the Carnegie Community Centre at the south west corner of the intersection, the 100-block of East Hastings and Main is the heart of the community and the fight to protect it from gentrification is fierce and ongoing. I love the quick rhythm and precision of the title poem, which maps the block and the people on it:

blue eagle cafe

hotel balmoral

blood stains

illegal

latino

black

aboriginal

white

trash

flashin cash

smashin locks

no detox

hundred block rock

need a place

say the faces

keith

senior citizen

leanin and dealin

flyin and dyin

welfare bribe situation

blue teardrop tattoos

what’s the plan

tear it down

let ‘em drown

too much reality

fixin in the alley

blood streamin

naked girl tweakin

hundred block reelin

vancouver’s first

western world’s worst

hiv

public health emergency

The concluding stanza of “hundred block rock” identifies the City’s tactics in their war on the poor:

vilify

isolate

incarcerate

decimate

don’t forget

hundred block rock

illegal

latino

black

aboriginal

white

trash

hundred block

crash

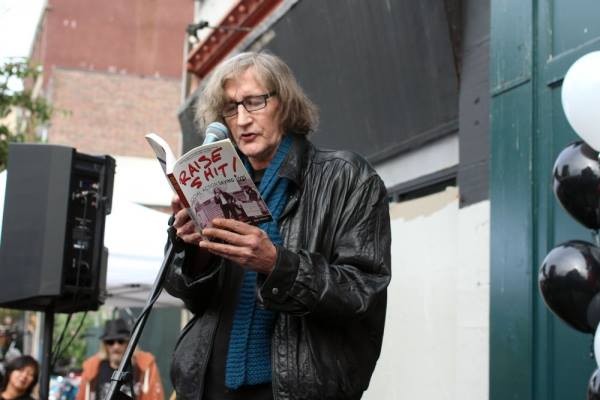

Osborn’s integrated practice of scholarship and poetry and activism is a powerful model for meaning making and making change. Like a scholar, Osborn cites the experts in the field of knowledge before joining the conversation; poems like “Raise Shit: Downtown Eastside Poem of Resistance” and “Take Back Space” begin by quoting academics on gentrification, but do so in a way that is accessible to those without postsecondary education.

Osborn read “Raise Shit” at workshop at the inaugural International Conference of Critical Geography held in Vancouver in 1997, situating gentrification in the City within a global context:

here is a planetary resistance

against consequences of globalization

against poor people being driven from land they have occupied

in common

and in community

for many years

and while resistance to and rapidity of global gentrification

differs according to specific local conditions

we in the downtown eastside

in the poorest and most disabled and ill community in Canada

are part of the resistance

which includes

the zapatistas in chiapas mexico

the ogoni tribe in nigeria

and the resistance efforts on behalf of and with

the lavalas in Haiti

the minjung in korea

the dalits in india

the zabaleen in Egypt

the johatsu in japan

and these are names for

the floor

the abandoned

the outcasts

the garbage people

the homeless poor

and marginalized people

and gentrification has become a central characteristic

of what neil smith perceives as

“a revengeful and reactionary viciousness

against various populations accused of ‘stealing’ the city

from the white upper classes”

Two months before he died, Osborn published “Take Back Space” in the Carnegie Newsletter, a bi-weekly community paper that has been operating out of the community centre since 1986. An astute analysis of the lessons activists can learn from the harm reduction movement regarding the reclamation of space, it begins:

I was talking last week with libby davies, member of

parliament for the downtown eastside of vancouver,

and libby told of a star trek episode she’d seen - a

futuristic situation in san francisco - an enormous wall

had been constructed dividing poor people from every-

one else .. and outside this wall

in super consumerist upscale society

there was almost no awareness of who was struggling

to survive on the other side of the wall

nor how wretched their living conditions were

and libby said “that’s not our future

it’s happening right now”

north america’s anti-panhandling bylaws and other

prohibitions against the presence of certain people

in what was formerly public space is a central objective

in the global and local writ against the poor

to put this situation in perspective I’d like to quote

from an excellent book “geographies of exclusion” by

david sibley; he says

“power is expressed in the monopolization of space

and the relegation of weaker groups in society to less

desirable environments .. the boundaries between the

consuming and nonconsuming public are strengthening

with nonconsumption being construed

as a form of deviance

at the same time as spaces of consumption eliminate

public spaces in city centres, processes of control are

manifested in the exclusion of those who are judged to

be deviant imperfect or marginal - who is felt to belong

and not belong contributes in an important way to the

shaping of social space

it is often the case that this hostility to others

this anxiety is reinforced by the culture of consumption

in western societies

the success of capitalism depends on it

and a necessary feature of the geographies of exclusion

the literal mappings of power relations and rejection

is the collapse of categories like public and private and

to be diseased or disabled is a mark of imperfection

the fear of infection leads to erection of the barricades

to resist the spread of diseased polluted others

there is a history of imaginary geographies

which cast minorities .. imperfect people ..

and a list of others who are seen to pose a threat

to the dominant group in society as polluting bodies

or folk devils who are then located elsewhere

this elsewhere might be nowhere

as when genocide or moral transformation

of a minority like prostitutes are advocated

the imagery of defilement which locates people

on the margins or in residual spaces

is now more likely to be applied

to the mentally disabled the homeless prostitutes

and some racialized minorities”

the downtown eastside of vancouver, where I live, is

by any statistical measurement of poverty and disease

a third world area

besieged by upscale developmental greed

of truly genocidal proportions

the highest rates and numbers of hiv/aids .. suicide ..

hepatitis c .. syphilis and tuberculosis

in the western world

and close to the lowest life expectancy

Close to the lowest life expectancy, Osborn’s poetic research informs me, the reason why I get a seniors card when I pay the $1 membership fee for the community centre even though I am in my early 40s.

Osborn’s memorial began in front of Insite, taking the street amd momentarily suspending traffic on one of the City’s busiest arteries, and ended at Oppenheimer Park. In 1997, the year VANDU formed, the year that, as a director of the Vancouver/Richmond Health Board Osborn was able to have a motion passed declaring Vancouver’s first-ever public health emergency, the year that 14 women from the neighbourhood were murdered, Oppenheimer Park was also the site of a memorial: the 1000 Crosses demonstration. DTES activists blocked traffic on at Main and Hastings then marched to the park to plant 1000 crosses to represent and honour the lives lost in the war on the poor. It is heartening to observe the manifestations of Osborn’s rallying calls to raise shit and take back space today at Oppenheimer Park, where a 2–months strong tent city stands to protest homelessness in Vancouver, one of the world’s most liveable cities.

Unceded west coast city: Vancouver