Downtown Eastside poets: Antonette Rea and Phoenix Winter

For weeks I’ve been trying to write this post on the Downtown Eastside, one of Vancouver’s oldest residential areas — historic home to many working-class immigrant communities and currently the City’s most contested and fought-for space as gentrification escalates rents and property values and poor and low-income people are displaced — anxious to do justice to a place close to my heart where much of my own history lies. How to write about the neighbourhood I have lived in for almost two decades, first as a drug user and sex worker and now as a college instructor? How to write about gentrification when I have lived for 15 years in the same relatively new condominium that helped anchor another wave of gentrification in the DTES, safe from precarity of the housing market and now typifying the new residents displacing the kind of resident I used to be? How to express the resiliency of some of the most marginalized people in the city, the people who make this neighbourhood a great place to live?

I hope to do this by historicizing the Downtown Eastside as a space of resistance and struggle for social justice, and by honouring DTES poets, beginning with Antonette Rea and Phoenix Winter, two of many women in the neighbourhood who fight to maintain the DTES as a place where poor and low-income people have the right to remain. Lived experience of mutiple and intersecting oppressions grounds their community involvement. Participating with Rea and Winter in various forms of activism, including poetry, has taught me a lot about my recognising my position of privilege.

Rea and Winter are contributors to V6A: Writing from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside (Arsenal Pulp Press, 2012) an important anthology of diverse DTES voices. In the introduction, coeditors and poets John Mikhail Asfour and Elee Kraljii Gardiner explain that the title “V6A refers to the postal code assigned in 1972 by Canada Post as a prefix for the urban Vancouver area known as the Downtown Eastside.” This designation also allowed for the collection of data, statistics that do not register “the intangibles, those unquantifiable aspects of community that cannot be charted or graphed […] reducing this geographic area to a catchphrase: “Canada’s poorest postal code.’” V6A challenges the dominant media’s shorthand for the area, instead pointing to the DTES’s wealth of artists and cultural producers.

Winter’s poem “Savour the Taste” speaks to the lack of concern for DTES residents at the lowest end of the economic spectrum, the City's poor who dwell in the neighborhood’s deteriorating hotels:

There's dirt under my tongue

teeth gritty

with flavours

of the Downtown Eastside.

It crumbles

from the Empress, the Balmoral

and the Lucky Lodge,

happy names

for such despair.

We are the expendables

in our reality show,

“Star Track” lives.

Feel the grains beneath

our hands

as we squat

on sidewalks.

I can smell my grave

here

not some fragrant, flower-strewn

cemetery

but ashes

flaky and acrid

choking my lungs

and my life.

Bury me

under the cherry trees

of Oppenheimer Park.

Let my fingers

wind in the blades of grass,

so soft, so comforting.

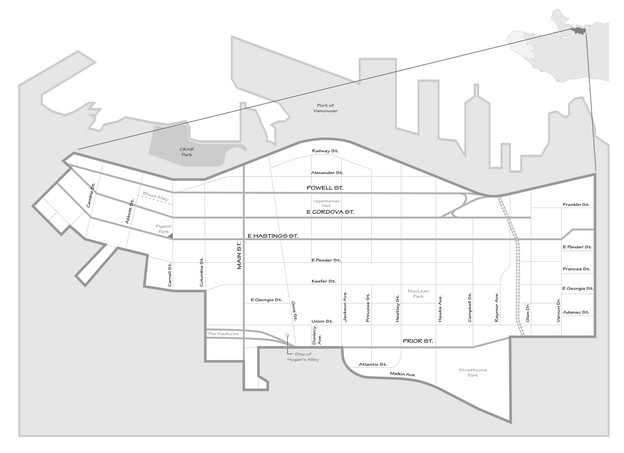

The cherry trees of Oppenheimer Park in Winter’s poem are the same trees under which people have been sheltering for the past two months to protest homelessness. They were planted by Tonari Gumi, a Japanese community association, to memorialize the Japanese Canadian centennial, which marks the arrival of the first-known Japanese settler. The Japanese community was located around Oppenheimer Park in the DTES until the government forcibly removed Japanese Canadians from the West coast during the Second World War. A few blocks South West was Hogan’s Alley, home to the Black community before it was torn down to build the Georgia Viaduct to facilitate traffic out of downtown, echoing the destruction of Black neighbourhoods in American cities through freeway construction. East of and adjacent to Hogan’s Alley is North America’s second largest Chinatown (behind San Francisco) where the Chinese community has been for over a century, where low-income Chinese seniors now face the threat of eviction. So, the Downtown Eastside is an area rich with the histories of multiple communities and also an area with a long history of displacing people, beginning with the Coast Salish peoples, the original inhabitants of this unceded land.

Rea’s “High–track, Low–track”, excerpted below, poeticizes the move from “High–track” in downtown Vancouver’s Yale Town as it becomes redeveloped, to “Low–track” in the Downtown Eastside:

Dates are few and far between,

pushed undercover or out to the Eastside

where ya get half the money

because the girls all service drug habits.

New condo developments increase the foot traffic

and the “not in by backyard” attitudes.

Most johns don’t want to be seen picking up a tranny,

ask you to follow a block behind or on the other side of the street.

Then, where to park, as the lots get developed.

New late–night drinking laws make it dangerous

on the weekend.

Ignorant tough youths

cruising in from the ’burbs

throw bottle of beer, eggs, and verbal abuse.

Rea’s poem troubles reductive media narratives that characterize the DTES as a violent and impoverished danger zone of drug addiction and sex work. Yes, poverty, violence, and addiction are problems, but Rea concretizes the problems trans sex–trade workers endure and sometimes survive so that responsibility lies with society not with marginalized individuals who often have health issues like addiction: transphobia and the processes of ‘urban renewal’ force them to work in spaces where lack of light makes them even more vulnerable to violence.

I am indebted to Winter’s and Rea’s survivor spirit and praxis of poetry, performance, and activism.

Unceded west coast city: Vancouver