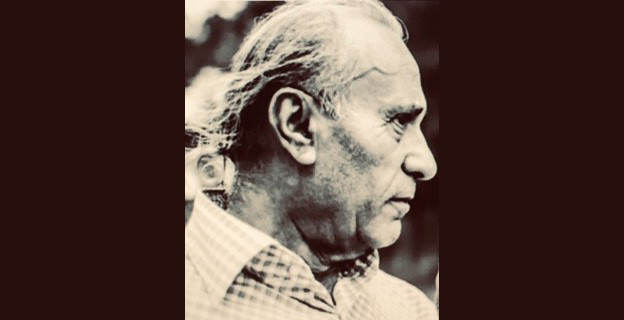

Wadiʿ Saʿada: poetry out in the open

The writers and artists of Beirut’s Hamra street remember a day in 1973 when a young man from the northern village of Shabtin stood handing out his poetry to passersby. It was Wadiʿ Saʿada (b. 1948) with a stack of handwritten copies of his first poetry collection, The Evening has no Brothers. Stepping outside the established avenues for “making it” in the world of writing and publishing, Saʿada placed himself and his writing out in the open, literally on the side of the street. He went out to meet the abstract reader, in person.

From distributing poetry on the street to publishing all of his work online, Saʿada is committed to the immediacy of poetic experience and to an unmediated relationship with his reader, without attending to the critical consequences. In his very first poetic statement, the opening of The Evening has no Brothers, Saʿada resigned himself to a rupture or a shattering that necessarily results in loss and disintegration:

In this village

the evening poppies are forgotten

shivering behind the doors.

In this village which awakens

to drink the rain,

the glass of the world broke in my hand.

(from The Evening has no Brothers, 1981)

the evening poppies are forgotten

shivering behind the doors.

In this village which awakens

to drink the rain,

the glass of the world broke in my hand.

(from The Evening has no Brothers, 1981)

Saʿada describes himself as a poet of texts not poems. He does not flaunt linguistic or formal feats but prefers to keep his poetic efforts all focused on the threshold of a project, an attempt, a beginning, not a thing as much as a gesture toward a thing:

The Drowning

raised his hand

as if he wanted

to say a word.

(from Most Likely Because of a Cloud, 1992)

raised his hand

as if he wanted

to say a word.

(from Most Likely Because of a Cloud, 1992)

A Lebanese émigré residing in Australia since 1988, Saʿada represents a turn in the Arabic prose poem away from the diligent interrogation of language. His concerns are outside the Arabic lanaguage as a poetic consciousness. Thus, his most successful perceptions seems to be preverbal, conceived in a space before language. He is preoccupied with the possibility/impossibility of speech in the first place. We also find in his work gestures towards other poetic traditions especially the American. However, they remains gestures and not a thorough intimate engagement as what we find in the works of more dedicated poets-translators such as his contemporary the Iraqi Sargon Boulus (1944–2007), another important figure in Arabic Modernism’s “Other Tradition.”

In the following poem, Saʿada gestures to Jack Kerouac from across the language divide, striving for a connection beyond or outside language, that disorienting heaps of signs.

Jack Kerouac

Many errors in the signs and the names along the way, Jack Kerouac.

The arrows pointing to places

lead to other places,

and the signs that say “springs”

are deserts.

What happened, Jack, that I now see the field as a whale about to swallow me

and the butterfly a wall?

Was the swallow that fell dead in front of me

passing through, tracing the way

or erasing the passage?

Jack, O Jack, take down the signs on the road.

Cancel the springs, the forests, and the places,

and point me to the path with no signs and no names.

I just want to pass through.

(from Who took the Glance I left on the Doorstep, 2011)

Earlier this month, Wadiʿ Saʿada won the International Argana Prize awarded by the Moroccan House of Poetry for his contributions to the Arabic prose poem.

Arabic Modernism's Other Tradition