Poaching the prospect

I had inferred from pictures that the world was real and therefore paused, for who knows what will happen if we talk truth while climbing the stairs. In fact, I was afraid of following the picture to where it reaches right out into reality, laid against it like a ruler. I thought I would die if my name didn’t touch me, or only with its very end, leaving the inside open to so many feelers like chance rain pouring down from the clouds. You laughed and told everybody that I had mistaken the Tower of Babel for Noah in his Drunkenness.

— Rosmarie Waldrop*, “The Reproduction of Profiles”

I was thinking about why I wanted to write about still lifes, which perhaps don’t seem so directly a ecological and/or poetic topic, really. I guess it’s partly because I think so much about intentional landscapes and the still life is a miniature of that. Still lifes also are an intersection between art/nature, and in the physicality of their arthood (artiness?), actual places in which to think about where the creative soul can have something to say about how we exist in and of nature.

But they aren’t of course actual places. They are compositions, re-compositions, of actual things and places. Maybe here I should talk about landscape painting, as well. Maybe I should talk about the difference between landscape painting and earthworks. But I might be more interested in the moment by intentional landscapes and the concept of “the prospect.” And how the prospect is a precursor (but a simultaneous one) to a landscape painting. And the prospect could be seen as an early form of an earthwork.

Raymond Williams touches way too briefly on what “the prospect” is. (And in that eerie way the mind can built up what one’s read, I could have sworn he defined it much more clearly than he actually does.) Anyway, “the prospect” is what the landowners created after they acquired (such a polite word, acquire!) all the land “freed” up (for them) from enclosing the commons (see John Clare). Poor John Clare—he was violently shoved into pastoral mode by large economic and social forces, and perhaps even the first recorded case of “ecodepression.” Take his poem “To John Clare”— a pastoral poem written under intense displacement, the immediacy of nature writing forced into nostalgia to the extent that the adult self is divided from the child.

Well, honest John, how fare you now at home?

The spring is come, and birds are building nests;

The old cock-robin to the sty is come,

With olive feathers and its ruddy breast;

And the old cock, with wattles and red comb,

Struts with the hens, and seems to like some best,

Then crows, and looks about for little crumbs,

Swept out by little folks an hour ago;

The pigs sleep in the sty; the bookman comes—

The little boy lets home-close nesting go,

And pockets tops and taws, where daisies blow,

To look at the new number just laid down,

With lots of pictures, and good stories too,

And Jack the Giant-killer's high renown.

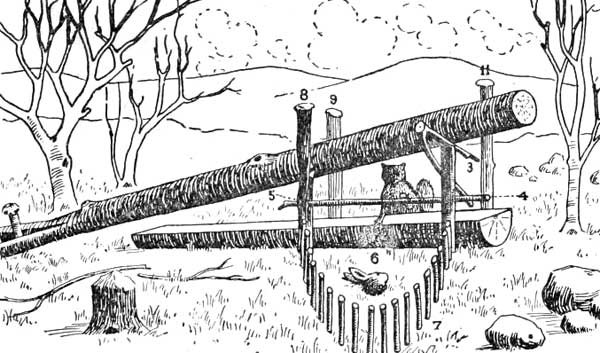

So, after land was taken and peasants kicked off, landowners would then immediately set about recreating a pastoral ideal that they could view from their windows—the prospect. Really, it seems the same “evict and evoke” process happening in cities today, where longtime inhabitants are priced out of a neighborhood and the new inhabitants (and developers) immediately set about evoking a sanitized fantasy version of what it was like just before they arrived there. The butcher shop is replaced by a more “charming” butcher shop—and what’s the difference? The people are gone. It’s the same thing with the prospect. The views are of sculpted formal gardens, a sweeping grass lawn, an artificial or natural pond, and woods framing the sides, and in those woods, “poachers” (former inhabitants of the land) are being chased off via gun and threat of imprisonment.

This post is getting long, but the prospect and enclosure have much to do with the false binaries of city/country, people/nature, savage/civilization. These binaries work for those who want to acquire and exploit land. Much of the people who lived on and from the land fled to the cities. Therefore, cities are dens of sin and disconnection. But prospects are beautiful, the views are exquisite—where does art and poetry fit in? Are we poaching, or aiding and abetting?

*Rosmarie Waldrop is reading tomorrow night with Marjorie Welish at the Poetry Project in NYC, by the way.

Geometries of landscape