Now, / about what to put in your poem-painting

In French, the still life is called nature morte or “dead nature” — appropriate for the posed piles of plucked fruit, cut flowers and dead fish, fowl or mammals that used to be painted by art students (my father still reminisces about how, if the teacher left the room, he and his hungry fellow students would ravage the pile, leaving apple cores and fish bones).

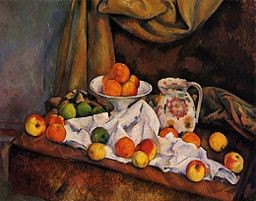

So, a still life is a composition — natural things juxtaposed with a human-made object such as a vase or glass — arranged for visual surfaces and shapes. Cezanne’s still lifes, for example, get down to the geometries (speaking of cores) of the artificial and natural — finding their essences as shape and color within paint. And thus the painting finds its own life; is brought into existence; has its own light, texture and color; is discrete from what it began from. Artificial and natural are made equivalent in this double process of composition (or “dividing the plane”).

What are still lifes like in poetry? I tried to think of poets who have arranged a pile of fruit and flowers, placed next to or within a vase, and then wrote while staring at that pile.

… Now,

About what to put in your poem-painting:

Flowers are always nice, particularly delphinium.

Names of boys you once knew and their sleds,

Skyrockets are good—do they still exist?

—John Ashbery, “And Ut Picture Poesis Is Her Name”

But the poet has already departed from the traditional still life by the time he’s reached “names of boys,” which are evocative, not observed. By the end of the poem, he’s veered into the impressive disjunct between the “extreme austerity” of the (almost) empty-headed poet’s head and the “lush, Rousseau-like foliage of its desire to communicate.” (Sigh. How true. Galaxies of language exist within that particular disjunct.) And then, thinking of other examples, for some reason Steve Zultanski’s efforts to lift every object in his apartment with his penis came to mind (in mind's mischief). No, no, no—one is not allowed to lift the objects of one’s still life with parts of one’s body, although there’s a certain continuum of engagement with the art students’ ravishment of their subjects. More somberly, then, there are Brenda Coultas’ linguistic arrangements of discard and detritus—the haphazard leftovers of voracious acquisition.

Poets may have detoured the nature morte — in writing poetry like a painting of a still life. Moving poetry through art from nature, to look at the process itself of artifice. Ekphrastic poetry in which the pastoral eye is moved from contemplation of the “natural” scene (which is, of course, completely posed — even the view is framed) to art of the scene, even the frame, and the gallery, and maybe how the art was paid for. Art has never been satisfactorily pegged as either natural or artificial. A painting (or earthwork) just doesn’t seem to inhabit the same universe as a plastic bag. But at the same time, everything human-made could be seen as somewhere somehow artful; some creative choice lurks in even the most utilitarian object (see Duchamp, Marcel — Urinal).

Geometries of landscape