Lions, mists, riot poems

Poetry, many cultures in many different times have decided, is a good genre for ecological thinking, for cataloguing and storing things humans need to know about the plants and the animals in order to survive. It is often, as many nations realize, a fine genre in which to incite patriotism. And similarly, many use it to articulate a love for a beloved.

And yet this morning, we were asking ourselves what if the riot is one of these things with which poetry also has a special relationship? We are asking this question naively, aware of its possible absurdity. Nervously even. We've said milder things, called milder things into existence and got called terrorists for it before.

We are asking it after reading Philip Levine’s “They Feed They Lion,”a poem he wrote about the five days of the Detroit riots of 1967. (And we’re just going to use the word “riot” and not “uprising” or any other possible euphemisms. We’re fine with riot. It doesn’t need to be a slur if we don’t let it be.) Levine called this poem a “celebration of anger.” It is a list poem full of repetition and sonorous rhythms. It is a poem that keeps amazing.

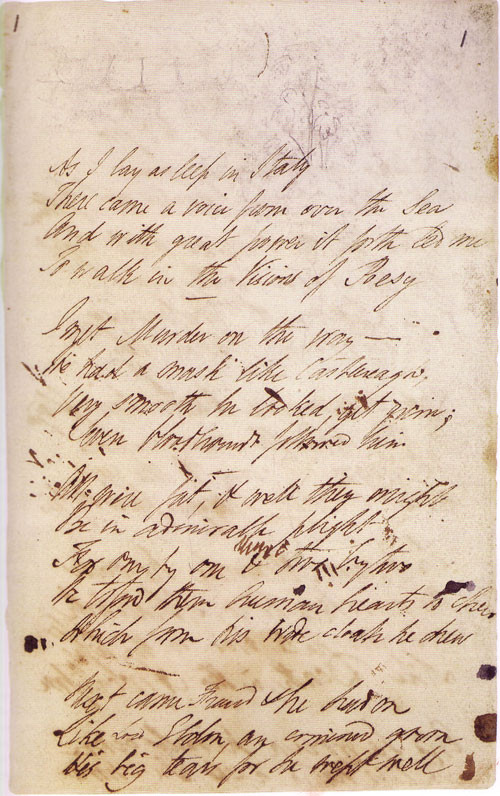

And then after that, thinking some about the lion we are to rise like after slumber in Shelley's “Mask of Anarchy.”

Levine attributes his lion line to the literal, to something someone named Eugene said when Levine and Eugene were sorting universal joints. But one cannot hear the line “they feed they lion” and the line ‘Bow Down’ come ‘Rise Up’” and not hear Shelley’s “Rise like Lions after slumber / In unvanquishable number, / Shake your chains to earth like dew / Which in sleep had fallen on you — / Ye are many — they are few.”

Although next thought: what Shelley? For that poem with its pun on swords and words has never had an interpretative clarity. Some use it to justify the rise up that sometimes gets called militancy. Some use it to justify passive resistance. We’ve thought often that the mist of that poem, the mist that seems to call forth the maniac maid called Hope, is this interpretative unclarity. (And we are often thinking of that Shelleyian mist more literally every time we click through our daily riot porn, which is often full of gases and mists of various sorts.)

And then we began reading, as if we had all day, in a sort of associational way. Turned to Claude McKay’s “If We Must Die,” written next to the red summer of 1919 when there were over twenty race riots where white people attacked black people. In many cities, black people fought back: “If we must die, let it not be like hogs.” This poem of such a rich history; it was read and recited by the prisoners of Attica before they began to riot in 1971.

Next spent some time with Gwendolyn Brooks’ Riot, about the 48 hours of riots in Chicago in 1968 after the death of Martin Luther King. We promised ourselves that we would return to this book in the future.

This list just the beginning of our noticing. There is a lot of riot in literature.

Our thoughts this morning are more associational than anything else. Is it just us, or is there a dry period of riot poetry in the 80s and 90s? We can remember them here and there. Myung Mi Kim, for instance, writes on the 1992 LA riots in Dura. She gives two pages; she quotes the mother of Edward Jae Song Lee who was killed during the riot; references the newspaper. But this poem is more descriptive. It isn’t the solidarity statement that is Levine, Shelley, McKay, Brooks, etc.

Then we thought it is hard right now to imagine someone writing a book defending a riot and calling it Riot. But why did we think this? Because our next thought was Sean Bonney.

We know though that we thought this despite Sean Bonney, and some of the works we hope to discuss in the weeks to come, because is easy to imagine the sorts derision that might accompany this book called Riot, the accusations of naivity, of wielding a rapier of coolness, of supporting totalitarianianism, of being an armchair leftist, easy to imagine all the comments that this imagined author might experience when they announce their publication of this imagined book on facebook. Why does so much of poetry land want to discipline and dismiss this sort of work? Why so much shaming of those who write about riot, protest, uprising? Why so much dismissal of the rich, diverse, and various traditions of writing that have supported them? Why do we not complain more about the relentless red baiting of this moment?

For as riots are a thing that happens, sometimes in our own backyards, why wouldn't they have a poetry? Or be a part of a poetry? Is it something to do with the genre? Riot porn, we get. We get why they call it porn. It excites. Inspires sometimes. But riot poetry seems less obvious. In part because, unlike riot porn, it is often recollected in tranquilty. So that has opened it to one easy accusation of being armchair. But then most poems are in some sense written from the armchair and that can't mean we all want poems that celebrate only activities conducted from armchairs. But then also a lot of the work that we admire that has been written in the last few years has been so not armchair.

Trying to begin to think on this, pulled out Spy Wednesday by David Brazil. In it he tells a story of being arrested in an anti-war protest (it probably wasn't a riot but it is a literary representation of protest so we're going there). We remembered that moment where he calls out his name: “As they were loading me in the van /someone yelled out “Whats your / name man?” And I cried out / real loud ‘David Brazil! / David Brazil!’ / Then I was in / the van. In handcuffs. / That's an experience. Solitary, / cut off, fettered.” When we first read this in 2008 we thought of the maqta of the ghazal. Today we thought about how there's all this stuff that happens in life. As landscapes exist, as love exists, as breakups exist, as patriotism exists, so riots exist (and seem to be happening more). And if nothing else, the poetry of riot is at least in opposition to a poetry of nationalism and that has to be a good thing.