Baraka / the divide

At the first poetry conference I ever attended, war broke out. It was the National Poetry Foundation’s North American Poetry in the 1960s, in 2000. Barrett Watten, fortuitously also providing Commentaries for Jacket2 just now, gave a plenary on “The Turn to Language after the 1960s,” which in my memory charted a two-way street between campus radicalism at UC Berkeley (both the Free Speech and anti-war movements) and a politics of form foundational to what would be “language writing.” In Watten's own words, “In my multimedia presentation, I tried to reconstruct a context for the poetry’s “turn to language” in the conditions of public discourse of the period, focusing on Berkeley as a site and Allen Ginsberg’s Indian Journals as a text, using Ernesto Laclau as theorist.”

From the back of the hall, Amiri Baraka wasn't having it. There are varying accounts of the debate, though few understate the vituperation. I was sitting just a few feet from Baraka and he was pissed. For some, the bone of contention was whether the FSM and the purportedly petit-bourgeois concerns of students offered a serious politics, and thus a serious way to understand the historical period, in comparison to the Civil Rights Movement, for example. Alongside this, there was a more immediate insistence that the militancy of the era was being recuperated into academicism: “Baraka...finally lashed out at Watten for being a ‘hyper-rational pseudo-radical’ and for ‘pimping‘ radical politics for his own academic benefit.” The argument might have gone all night but for the hasty intervention of the organizers, who arranged for the two to continue matters the next day during a special lunchtime debate.

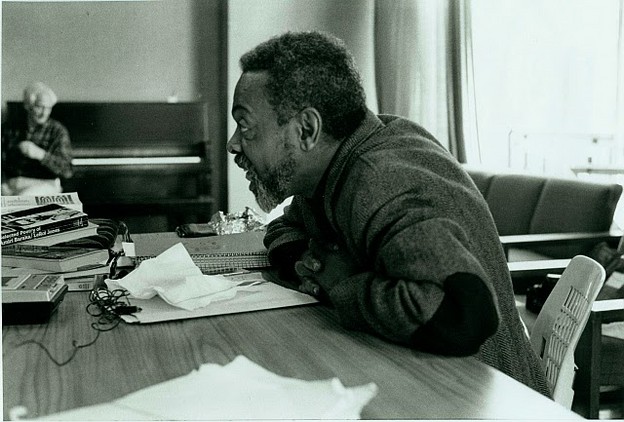

Of that latter event, I recall largely the set-up. Watten arrived loaded with books to argue his position, which he built into a fortification of texts on the folding table: here, surely, was the materiality of the signifier. Baraka, in counterpoint which would have been comedic but for the charged atmosphere, pulled from various pockets some wadded notes. The divide between the two could not have been more decisive. In memory, it reduces easily to clichés: the militant and the scholastic, town vs. gown, raced and classed, divided by irreconcilable structural positions.

The tension nested most dramatically in one exchange. Watten had shown a clip from a PBS dcumentary in which a former Panther claimed that they had raised money for guns by buying Mao’s Little Red Book cheap in Chinatown and selling it dear on the Berkeley campus; the Panther claimed not to have read it himself. For Watten, this made of the celebrated text an empty signfier. For Baraka, this move effaced one of the signal political events of the century. “And besides, this is just one man who said he hadn’t read the book. We read Mao, Baraka insisted.”

I was put in mind of this as Baraka has been in the news of late; he turns 80 this year, and his health has been uneven. The prospect of living in a world without Baraka is a bleak one. He is not without failings — human, all too human — but he wrote eighty great poems and he wrote

you cant steal nothin from a white man, he's already stole it he owes you anything you want, even his life. All the stores will open if you will say the magic words. The magic words are: Up against the wall mother fucker this is a stick up! Or Smash the window at night (these are magic actions) smash the windows daytime, anytime, together, lets smash the window drag the shit from in there. No money down. No time to pay. Just take what you want.

There is something from that 2000 debate which seems paradigmatic, if misleadingly so. The skepticism about university leftists in relation to communities of color and political organizing casts a long shadow in the Bay Area, where Commune Editions lives. The contemporary association of Marxism with whiteness, bourgeois hypocrisy, obfuscatory theory, and scholasticism is not universal, but not uncommon either. In this context it is salutary to be reminded with a start that Baraka is a Marxist, was one in 2000 as he pulled the scraps of paper from his pockets, was one when he joined the Congress of Afrikan People, which would become the Revolutionary Communist League.

It is difficult now to imagine the commingling of cultural nationalism and Maoist thought, to imagine its prevalence in the sixties and seventies among intellectuals and militants, to imagine the synthesis of positions to which this tradition aspired — a systemic critique of capitalism staged from the position of the peripheral, the colonized, the underdeveloped world, the subjects of empire domestic and global. Perhaps it is easier to see in France for example, where past and present Maoist intellectuals remain international figures: Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Badiou, Julia Kristeva. Jean-Marie Gleize, just translated into English, is scarcely the only poet who identifies thusly. In the United States, a set of phantom oppositions render such a confluence practically inconceivable. It has for the most part been forgotten that the Panthers themselves, adopting and adapting elements from Mao, moved from black nationalism toward revolutionary internationalism, much as did Baraka.

It would be easy enough to reflect on that world’s passing away — there’s always room for more left melancholy! Moreover, the limits of Maoism and third-worldism deserve attention. But not here, not now. The document that I have found most moving in the last year is the list of books taken from George Jackson's cell in 1971, after his shooting by prison guards. It has its oddities: Euell Gibbons? And so few women! But I wish that my friends had read half of these books. I wish that I had. This is part of what Baraka means. For the present I want to hold on to the possibility that we are at a divide, that the moment in which the opposition between clichés of intellectualism and clichés of militancy might dissolve is both behind us and ahead.