Gwendolyn Brooks's 'Riot' and the opt out

As we’ve been writing about our thinking over the last few years, we’ve been attempting to understand what sorts of forces shape poetry. We have often turned to political economy to attempt to understand the impact of late 1970s precarity on the genre. At other moments we have attempted to understand the poetry institutions — its conferences and its foundations and its not for profits and its publishing houses and its creative writing programs in higher education and its distribution modes and also its DIY tendencies. At other moments, the state’s funding of poetry and use of it in soft diplomacy. As we have written these thoughts, we have not arrived at any sort of easy and legible story. If anything we've noticed a sort of mess of connections among these various sorts of things, forces that push and pull contemporary production in various often contradictory directions.

Not infrequently, as we have shared these thoughts, it has been presumed that we have some sort of ideology of purity. That we think that if one just refused to do something — to teach in a university, to go to AWP, to not apply for an NEA — then one's poetry could be free or ethical or politically right. And yet that has not been our intention. We are not convinced that one can opt out of much of this. Or at least not conference by conference. Nor one by one as individuals. All of these forces write all of us. We feel these pressures on our own work and we know we are involved in many of these institutions and we do not know how to opt out of them in this current world we live in (and part of our interest in attempting to think about what poetry might look like in a different world after a revolution originates with this realization). Plus, we are often naïve; at moments we don't even know what we are getting ourselves into. Once we did a workshop for a week in Tijuana. When we finally got paid, we noticed the check was from the Department of Energy. We still do not know why the Department of Energy was funding cultural diplomacy, but when we got the check we had the slightly queasy realization that we had naively agreed to be a part of the soft power of the Department of Energy and not realized it. And yet to not attempt to understand these forces as an artist and to say well the fact that the workshop was sponsored by the Department of Energy doesn't matter because poetry really doesn’t do anything and the Department of Energy (here functioning as a wing of the State Department) is dumb to think this or to say we talked about Mark Nowak's Coal Mountain Elementary and that book is very cool and also workerist and about the damages of energy would be naive at best. If poetry does nothing really meaningful for the state, the state’s involvement in poetry does something to poetry. Figuring what it does seems part of what poets should be doing.

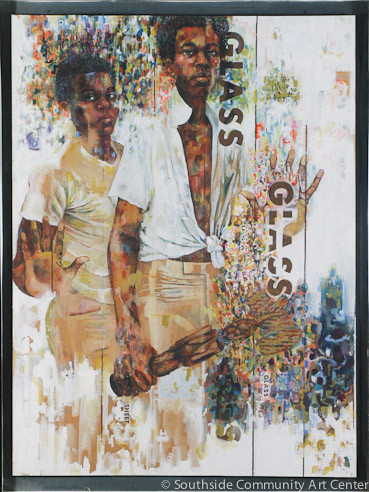

As we keep thinking about these forces, we've been interested in the example of Gwendolyn Brooks, especially her short book (chapbook might be better word) Riot. We came to Riot because we wanted to write something about literary representations of riot. And there is a lot to be interested about how riot gets represented in Riot. Riot is about the riots in Chicago after the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. Riot is beautifully designed, and every design decision feels loaded with accusation. There is a black first page with a Henry Miller quote from Sunday After the War in white type: "It would be a terrible thing for Chicago if this black fountain of life should suddenly erupt. My friend assures me there's no danger of that. I don't feel so sure about it. Maybe he's right. Maybe the Negro will always be our friend, no matter what we do to him." On the flip side of this, there is a return to a white page and on this page is an image by Jeff Donaldson. The painting shows two figures, one holding a figurative wooden sculpture, hands pressed against glass (the glass here represented literally by the word "glass"). It is hard to tell if the sculpture will be used for some window breaking or not but it is a possible reading. Donaldson was one of the founders of AfriCOBRA (African Commune of Bad Relevant Artists), a collective of artists that was formed in 1968 with a commitment to “the collective exploration, development, and perpetuation of an approach to image making which would reflect and project the moods, attitudes, and sensibilities of African Americans independent of the technical and aesthetic strictures of Euro-centric modalities.”

The poem itself is in three parts: “Riot,” “The Third Sermon on the Warpland,” and “An Aspect of Love, Alice in the Ice and Fire.” The first part tells the story of one “John Cabot,” “all whitebluerose below his golden hair.” He is repulsed by the riot, coming to kill him. He seems to die at the end: “John Cabot went down in the smoke and fire / and broken glass and blood.” This is a revisionary, and perhaps we might say even aspirational, history. Although eleven people died in the riots, all were black. The sermon that follows is subtitled “Phoenix” perhaps (the typography requires interpretation). It opens with the pastoral, lyric: “The earth is a beautiful place. / Watermirrors and things to be reflected. / Goldenrod across the little lagoon.” But the strength of this section is how it uses collage. This poem, the longest in this short book, juxtaposes different thoughts about riots from figures such as a child, newspaper accounts, "Black Philosopher," "White Philosopher," and others. And then the poem ends with a love poem, with a lover invoking a beloved, that is resolved in a final “we”: “We go / in different directions / down the imperturable street.” This is a great poem. We think we can say that. It is innovative and experimental for those who like that. It is “political” for those who like that. And it is crafted with an aware aesthetics for those who like that.

But as we've thought about this poem, we keep thinking about Brooks’ decision to opt out of the mainstream publishing and distribution modes. There are a set of interesting overtones around the name “John Cabot.” It is the name of an original Boston Brahmin, about whose family it is famously said, and this is good old Boston, the home of the bean and the cod, where the Lowells talk only to Cabots, and the Cabots talk only to God. The Lowells will eventually include Robert. The East Coast publishing industry is endlessly entwined with this old money/new world milieu — and it would be from this that Brooks would go a different direction. Riot was published by Broadside Press in 1969. It was Brooks first book published after she decided to leave Harper & Row and seek publication with a black publisher. James Sullivan (in "Killing John Cabot and Publishing Black: Gwendolyn Brooks's 'Riot'") calls this decision, in an article that muddies the differences between “cultural capital” and actual capital, a “profoundly anti-economic move.” We'd have to see some actual sales numbers to figure out the actual economics of this move. But at a certain point while Brooks clearly believed in the opt-out, which might be best thought of as an opting into community publishing; she repeatedly said in interviews that she did not leave Harper & Row because she had a critique, but because she wanted to support black publishing. Two things interest us about this moment. One is that when she opted out, there was still a Harper & Row that published poetry. Right now, poets can’t really opt out of much when it comes to publishing poetry. And yet it would be absurd to be nostalgic about the midcentury US publishing business. It was more or less a gentleman's business. But in that way that things tend to go from bad to worse, in the years since, publishing has polarized. There are now very few large corporations and a large number of very small presses. John B. Thompson, writing about the changes to the industry in Merchants of Culture, tells a story of two phases of consolidation. One from the 1960s to the 1980s where publishing houses looked attractive to multinational corporations because of possible synergies between various information and entertainment industries such as education, Hollywood, technology. And then one from the 1980s to the present where the development of retail chains (at the expense of independent bookstores) massively increased the possible volume of sales of a very small number of bestselling titles. So more money could possibly be made but by fewer titles. This in turn increased the power of ancillary industries such as agents and distributors. These publication and distribution models have a fairly significant impact on literary production. The larger houses took fewer risks on unconventional material. The middle-sized houses (which long supported literary fiction) disappeared. And the smaller and independent presses proliferated. Thompson when he writes of these two very different spheres of literary production writes of how the smaller presses survive through "an economy of favours." These smaller presses support each other. And they survive basically through favors from freelance designers and independent bookstores. When Thompson describes this economy of favors, although he does not describe it this way, he is basically describing a somewhat fixed but still somewhat market driven system.

Brooks’s decision to publish with Broadside Press is probably best understood not as meaningful economic support for Broadside but as a part of an emerging economy of favors. When we try to understand what it is that literature is up against right now, it feels useful to think of so much of what happens as caught in this economy, which is neither a real economy nor in any way really free from it. This is the situation, the way-things-are, but it is also a snare, of the sort we suggested at the beginning. You don’t get to leave the economy via some illusory choice, you must submit to it in moment after moment. And yet, no matter how many times you and others point out the contradictions, you don’t get to leave your commitments either — even if this is what would be easiest.

The contradiction isn’t abstract. It is always changing and moving and twisting poets, people, this way and that as history explodes and transforms us. So maybe another question to ask is, what role did the poem itself play in the way that Gwendolyn Brooks wrestled with this contradictory situation, which is in many ways now even more intensified? Autonomous publishing cultures don’t make much of a difference at all when detached from active political projects. This is especially the case in the present age, when the boundaries between DIY and corporate cultures are increasingly diffuse. Various processes of “disintermediation” and “reintermediation” associated with big firms like Amazon, Ebay, Etsy (and newer arrivals like Airbnb and Lyft) might eventually render the distinction between the “economy of favors” and the economy as such negligible. This is why the independent publishing of a book like Riot derives its real power from the insurgent energies of riot itself.