How to witness without seeing

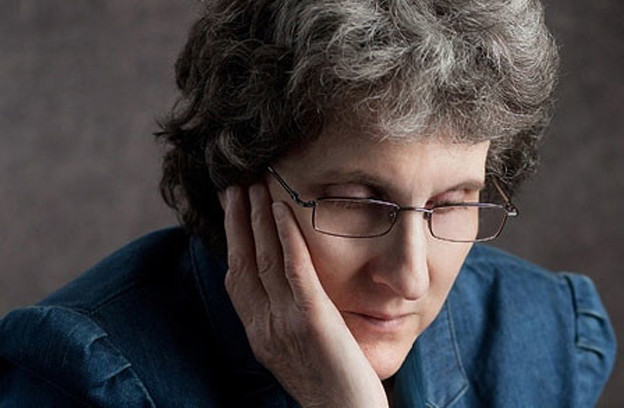

An interview with Kathi Wolfe

In Kathi Wolfe’s introduction to We Are Not Your Metaphor: a disability poetry anthology, she writes about the long literary tradition of using disability as a metaphor for all things bad: “How often have you read poems that use blindness as a metaphor for spiritual ignorance, unthinking faith, or moral failings? Or deafness used as a metaphor for isolation, aloneness — a failure to emotionally communicate? Think: world of darkness. Deaf ears. Crippling rage.”[1] While she doesn’t think poets can excise figurative language from their writing entirely, she does argue that metaphors reclaimed and influenced by the materiality of lived disabled experience can make our poetry less derivative and more specific. This argument isn’t just a theoretical position for Wolfe; she applies it in her writing.

In the poem “Blind Spot,”[2] Wolfe reclaims a metaphor overused by fellow social justice advocates to denote some area of their privilege to which they failed to attend. In “Blind Spot,” it’s seeing that isolates the observer, not blindness. When the speaker is observed by the sighted addressee, the addressee sees: “… a sightless / damsel in distress, / at sea in the darkness, / sexy as a nun’s lingerie.”[3] They are unable to spot the blind/low-vision speaker and witness what’s actually in front of them: “Sappho with her cane, / taking on the night — / a true-blue dyke.”[4]

Wolfe is a member of many literary communities, including the Washington Blade (the oldest and one of the most acclaimed LGBTQ papers in the United States) and the Lambda Literary Foundation (which supports and advocates for LGBTQ writers). She is also the impetus for the founding of Zoeglossia (a group dedicated to creating community for disabled poets). She writes from her experiences at the intersections of multiple positionalities: “being older, queer, a feminist, and disabled.”[5] As you read this interview, may you witness what she has to say without letting any sight spots get in the way.

Jessica Suzanne Stokes: How does your experience of disability impact how you write? In what ways does it inform and shape your methodology?

Kathi Wolfe: Trying to unpack how disability impacts how I write is kind of like trying to talk about what it’s like for me to breathe. It’s so much a part of my life and work. Though it’s a profound part of my life and work, I often don’t think about it. I’ll tackle the methodology part of your question first:

Because of my vision impairment, I do a lot of thinking and writing in my head. Sometimes consciously. Sometimes unconsciously. I read by listening to audiobooks, by Kindle, or on my iPad. I’ll read poetry often as a PDF on my iPad, because PDFs don’t screw up the line breaks. On Kindle, iPad, or in a PDF I can enlarge the text. When I can find it on audio format, I’ll listen to poetry, and I go to as many poetry readings as I can.

Sometimes, my line breaks in my poems are odd. I think this is because I’m not thinking about what the page looks like as a person with 20/20 vision. Dan Simpson is a blind poet and musician whose work I love. Dan is totally blind. He’s written about how for a while he tried to work with line breaks as a sighted person would. But, then, he worked with the poet Molly Peacock. She suggested that he stop dealing with line breaks as a sighted person would. She said, why not use sound to form line breaks?

I’m in the middle, between a poet with 20/20 vision and Dan. I think about line breaks. But I don’t think that much about line breaks. If a sighted poet says a line break is really odd, I’ll change it. The same way that if a person with 20/20 vision says my shirt doesn’t match my pants, I’ll change my shirt. And, because of my vision impairment, I don’t do concrete poetry.

How does my experience of disability impact my work?

Poetry is from the body (our personal bodies and, broadly, the body politic). I write poetry from a disabled body. And I live and work in a culture where every act that we do — in our lives and in our work — is, speaking broadly, political. Because we live in a culture where many can’t believe that disabled people can live, love, work, travel — even do something as simple as order a meal in a restaurant by themselves.

My experience of being disabled and/or disability doesn’t appear in some of my poetry. Much of my poetry deals with love, loss, death, wonder, searching for meaning — the usual poetry subjects. So my disability isn’t apparent in these poems. Yet, I think, disability is there. The same way that Windows is always there on my computer even though I’m not thinking about it at all.

Because I’m disabled, writing poetry is a political act for me. Even if a poem doesn’t deal with a social justice issue. Because of the low expectations of and devaluation of disabled people in our culture.

Much of my poetry isn’t directly autobiographical. I’ve written a lot of persona poems — from my Helen Keller poems to my Uppity Blind Girl poems. Yet, all of my poems are autobiographical in the sense that I create them. I have no idea how the creative process works. But my work is informed by the fact that I came of age at the beginning of the modern disability rights movement. I believe in disability rights and culture.

Like many of us with disabilities, I write (at least I hope I’m writing) authentically about disability. I’m writing from inside my body. From the experience of loving, knowing, working with others with disabilities.

Given how prevalent ableism is, it’s almost impossible not to have within ourselves some remnants of internalized ableism. Given that, I try as much as I can in my work to avoid ableist metaphors (like “crippling rage,” “deaf ears,” blindness being “a world of darkness”).

Often, I (or my characters) have reclaimed metaphors. Uppity Blind Girl plays with — reclaims — metaphors. I try in my poems to have disability be a part — but not the only part — of a character or of a moment. Because intersectionality is so important in our lives. We’re not just disabled. We’re hetero or straight, black, white, brown, Christian, Muslim, Jewish, Hindu, atheist, male, female, young, old, etc. So in my work, disability intersects with other parts of identify. For example, I write of my experience with disability and anti-Semitism in my poem, “What I Saw.”

Stokes: What would be the best possible outcome for your work? What might it do in the world, and how will its presence facilitate your role in your community?

Wolfe: Well, I have a new book out this fall: Love and Kumquats: New and Selected Poems. I’m excited about it! It’s a mosaic of my work from the Helen Keller persona poems to poems of love, grief, and loss. I hope people will read it and like it!

I hope that my work (particularly, the Helen Keller poems) will reveal some of the hidden history of disability. Helen Keller has been a victim of “inspiration porn.” Because of The Miracle Worker, this “inspirational” view of Keller has influenced how many people view disabled people. I’m not a historian. Yet, I hope that my poems will help people to see Keller as a fabulous, but flawed, human being.

I hope people will like Uppity Blind Girl. There aren’t many three-dimensional disabled characters in poetry or fiction. I hope Uppity will make nondisabled readers get the memo: disabled people fall in love, enjoy sex, work, go to bars, act like brats, get jealous, fight with but dearly love their sisters.

The last thing I’d do would be to write my poems to be “inspirational.” Yet, a few people have told me that after meeting Uppity they felt more comfortable leaving their house or speaking up for themselves. I hope my Uppity Blind Girl poems will encourage people to speak up when they encounter prejudice.

You never get over grief. I don’t expect my poems on loss to help people find “closure” or get over losses. I didn’t write my poems about loss as therapy for myself or others, but I hope that maybe these poems might help folks feel that they aren’t alone.

Helen Keller worked tirelessly for social justice. She didn’t use the word “intersectionality,” but she worked at the intersection of race, feminism, classism. She was very much of her time. She had beliefs (such as her support of eugenics) which repel us now. Having said this, I hope that reading my poems about Keller will engage people in the struggle for social justice.

1. Zoeglossia Fellows, We Are Not Your Metaphor: a disability poetry anthology (Minneapolis, MN: Squares & Rebels, 2019), 1.

Discordance: Disability Poetics In Process and Community