Woo

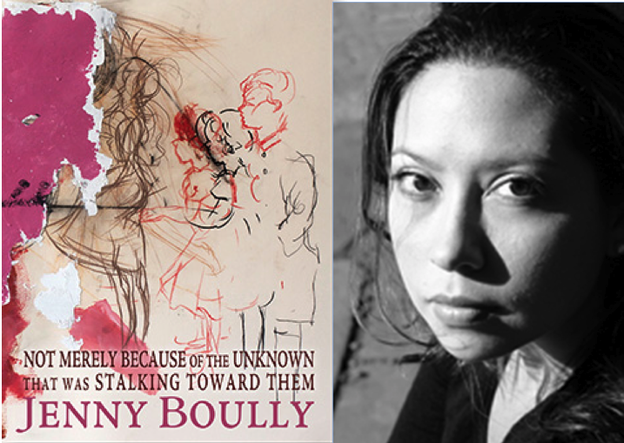

A review of Jenny Boully's 'not merely because of the unknown that was stalking towards them'

not merely because of the unknown that was stalking toward them

not merely because of the unknown that was stalking toward them

You’ve gone and forgotten all about your muffins, and you’ll now make

excuses and say well then they were only make-believe, but we all know

better: a fire and smoke that’s been here for days and days. (35)

Jenny Boully’s reading of J. M. Barrie’s Peter and Wendy (1911) prompts us to ask if we had known in childhood that the lure of childhood would not cease to woo, would we have understood what the lure was then? Have adults always been afraid to wait in a place they do not yet know? The back cover of this fiction/poetry collection advertises a “dark re-visioning” of Peter and Wendy’s story, though more it offers perspective on what the fairy tale ruins in Wendy and how the slippery perma-innocent Peter conquers his foe. No victory trumps forgetting, if one is remembered.

If the propagators of Barrie’s story are enamored with the naïf, the originating text is as grown and grim as they come: “That is all we are, lookers-on,” he writes, “Nobody really wanted us. So let us watch and say jaggy things, in the hope that some of them will hurt.”[1] The “we” here refers to a first person narrator the author inserts among the children to defend his portrayal of their mother, Mrs. Darling, as a finicky domestic with “no proper spirit.” “I despise her,” the writer-narrator admits. Boully’s keen commentary on such a text is clearly justified: the cycle of the book and its metaphor require a recurrence of wedded cherubs to fall from girlhood into marriage, dowry for doury. Wendy follows in her mother’s footsteps, as her daughter Jane too joins Peter, and in time her daughter Margaret will play his nursemaid and chef, “and thus it will go on, so long as children are gay and innocent and heartless” (242).

“Heartless” is a wry description of children and Barrie thus closing the novel calls attention to it. “Each day I cut a bit of sunflower,” Boully writes, “and take it. Home. Will Peter notice these?” (65). Does any child notice what is done for him? If gratitude is learned by loss, Peter’s poor memory cancels even the gesture of Tinkerbell to save his life. He not only forgets that she risked her own by swallowing poison Hook meant for him; he forgets her entirely. Boully calls such character into question and with it that long-standing love affair with youth, a flight one takes before learning how to stop (53). The parallel final word in Boully’s text is “outgrown,” as in hollow cradles under a moon swelled “so full” with the light of loss (65). The bough bent with big babies snaps when one has done with the idealization of never growing up.

“I will give you a thimble so that you will know the weight of my heart,” Boully’s second paragraph states: “A thimble may protect against pricks” (1). The hearts of the Darling children are as unguarded as that window Peter flies in to rifle them with dust. not merely contributes so rich a reading to Barrie’s text it should be assigned as a prep course for adolescents loosing the anemones inside their chests and a refresher course for fortysomethings who have forgotten the point.

The pull between freedom and time is a complicated one, and Boully holds in her form the two birds of this paradox by alternating arcs throughout the text. The first begins with an untitled section that converses with the novel via such reflexive statements as:

that is the story he will tell you … Oh Wendy … He will come to you

in the darkest part of night when you are sleeping and play upon

his pipes until you stir. (1–2)

Hip to the jig and rippling with innuendo, this thread is interrupted regularly by “The Home Under Ground,” named for the cavern Peter and the Lost Boys keep in Neverland. The structure mirrors the lock and lush of these asynchronous worlds: Peter’s game of pretend is made real not by the heart that darts away but the one that lands. Poor steady bird is a Never bird, wooed to follow nest and all.

“See Wendy,” Boully explains the paradigm: most want to have their cake and eat it too. Not Peter. He found an escape hatch in the clause — dispossession: “he doesn’t want to have the cake; he wants to eat it.” (46). Held “cake gets old; gets old” like Wendy and her “old lady” panties and Tink with her skeleton leaves, both of which Peter out flies, abandons, drops. Is the only way to “beat the game,” Boully asks, to play dead? (46, 20). How is it that Peter lives? He becomes Godotlike, as anticipation of his entrance kindles hope and Byronesque as he taunts that “it is not so difficult to die” to all that bloody mediocre life.[2]

“Pan, who and what art thou?” Hook asks, and Peter calls back “I’m youth, I’m joy, I’m a little bird that has broken out of the egg,” but his lines are “nonsense,” Barrie’s narrator interjects, except as “proof … that Peter did not know in the least who or what he was, which is the very pinnacle of good form” (208).

Barrie’s male protagonists are preoccupied with form, good and bad. The sloppiness, for instance, that causes Peter to take Hook’s suggestion in midair and kick instead of stab him, allows Hook to meet his defeat in peace. If men are but players on a stage, these two measure themselves like fencers by tallying the points of their performance. The rules of form and Peter’s moral caliber in relation to it are defined by Barrie in the chapter “The Mermaid’s Lagoon.” In it, Peter and Jas. Hook meet on a rock. Not insignificantly, Barrie refers here to Peter as “the only man the Sea-Cook had feared” (127, emphasis added). The man-boy’s seriousness is evidenced when he has the chance to stab Hook, but recognizing he has the higher position, offers a hand that Hook bites. Stunned by iniquity, Peter is made “helpless” and defeated — as all children are, Barrie says, the first time they are treated unfairly. But none else recover so completely and this distinction is what makes him Pan.

Perhaps his choice seems not an option for Wendy or Tootles or Smee or Tink, but to begrudge him it is the real cause of battle — wherein enter sorrow, violence, envy, seemingly justified by the slight of his forgetting. The choice should be examined closer, coming as it does in a book appropriated for children but first marketed toward adults. In the passage that precedes it, for example, Peter achieves such high-functioning psychological effect as to mimic Hook’s voice so well Hook “felt his ego slipping from him,” thinking Peter to be himself and separate, which scares him hoarse (123). Such results, if unconsciously administered, imply a greater symbol in Peter than irresponsibility. His readiness to forget may even be an act of generosity so daring it unmans him repeatedly — to forgive. As anyone attempting to clear the slates of injustice may guess, his magic may be deserved.

Certainly his self-forgetting is exemplary. The complication enters when that forgetting encompasses others, especially the doting Wendy, toward whom Boully’s pathos appeals. The defense is long-coming. The poignancy of Wendy’s role has been sandbagged since her name was excised from the novel’s title, published in 1911 as Peter and Wendy and limelit later solely for him. Boully intercedes on Wendy’s behalf:

“Betwixt-and Between” that

“male hand … scrawling on a little girl. All over, that is.” (56)

In not merely, the tables on which attachment and freedom play are not reckoned but turn. A mother, Boully says “is someone who always contains two things” (32). not merely contains more than two, but these — that love can act in memory and it must last to be believed: “No one wants to love forever a wild thing” (52). Except Peter, who keeps prying himself free — not away from but to love. To accept such possibility is to forgive even him — “wolf one” whose death Wendy will ever-after mourn (49). But, “for now: peaches:” empathy for the wicked, courage after one — to get past wolf two and the rest of them to a place where,

there should always be more. Love involved. (49; 58)

[1] J. M. Barrie, Peter Pan (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1953): 215.

[2] Lord Byron, George Gordon from Manfred, quoted in Oliver Elton, ed. A Survey of English Literature 1780-1880,ed. Oliver Elton volume 2 (Charleston, SC: Nabu Press 2010), 164.