Whose hearts are a thousand chemicals

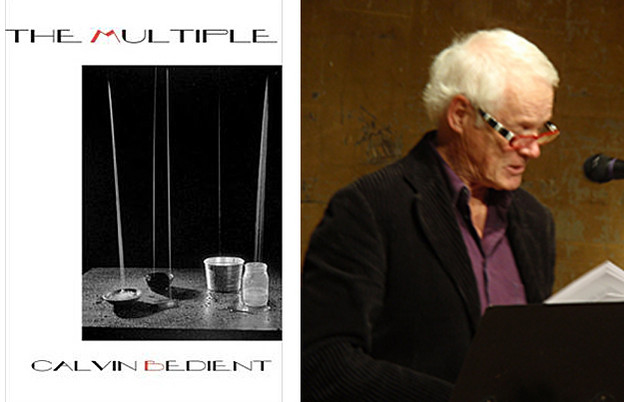

A review of Calvin Bedient's 'The Multiple'

The Multiple

The Multiple

Calvin Bedient’s fourth full-length volume of poetry, The Multiple, realizes the lines of multiplicity initiated by his previous three collections (Candy Necklace, 1997; The Violence of Morning, 2002; and Days of Unwilling, 2008). These earlier collections suggest the plurality of experience by gathering and juxtaposing snapshots of perspective to insinuate the whole. The Multiple takes this approach a step further by explicitly pointing its particular sampling of reality’s permutations toward the infinite outline of the unexcavated majority. The poems of The Multiple are as interested in communicating the negative space of what can’t be captured as they are in the positive space of what can. Bedient’s unwavering fix on the subjectivity of everything unleashes a “huffing accordion commotion” whose implied poetic production spreads well beyond the constraints of the physical book that delivers them. “Becoming’s a broken idea,” these poems insist (16).

Bedient frames his text as a series of fragments drawn from not one, but a choir of indefatigable epics, whose sample size has been limited to the standard length of a contemporary volume of poetry. Bedient’s distinctive poetic timbre permeates these poems, yet he maintains a stance that is distinctly more curatorial than authorial. Bedient positions himself as an archaeologist — or perhaps more accurately an astrobiologist — listening for “a palmful of memory-pollen” to reformulate “the lost chord innumerable in the dark / hubbub of the stars” (47, 67). Just as the presence of exoplanets can be inferred by the gravitational wobble they induce on the observable stars they orbit, the restricted space established in The Multiple resonates with implied systems of unseen verse and unrealized sequences.

Indeed, to describe this book as a “collection” of poetry is to underestimate the complex relationship between these poems and their poet. An anthology of reworked translations might be a more apt description of “this thing come into my heart / many centuries old” (13). By presenting himself as the conduit rather than the origin, Bedient further emphasizes the inevitability of missing elements — and the primacy of negative space. Bedient boldly declares his fixation on the overarching specificity of everything.

Bedient’s typographical choices reinforce this sense of universal expansion. One striking example is the use of nine different typefaces to present the titles of the forty poems that appear in the text. As The Multiple progresses, many of these typefaces are additionally filtered through a variety of fonts. These typographical signposts label a series of poetic systems and sub-systems that extend and overlap those already established by the book’s three asymmetrically weighted sections. While the most abundant typeface is used to title more than half of the book’s poems, others, including the typeface used for the body of the text, introduce only a single poem. As a result, there’s a distinct sense that many poems are missing here, if not entire groupings. What might otherwise read as typographical frivolity outlines a web of resonance that establishes each poem’s membership in a series of interleaved groupings, both observable and implied.

These phantom limbs further extend themselves by overlapping those systems already established in Bedient’s previous volumes. For readers familiar with any of these three works, The Multiple’s “discriminate/indiscriminate rain” (59) might become the “unitemized rain” of Candy Necklace[1]; The Violence of Morning’s “arrhythmical mass writing of the rain”[2]; and/or “the imperial redundancy of rain” from Days of Unwilling[3]. In this way, each of Bedient’s earlier books becomes a potential recruit in realizing the implied fragments of The Multiple.

While the text is filled with the sorts of finite moments that define the human condition, The Multiple rarely stops to muse for long on any single moment in the multidimensional field of experience. Bedient relentlessly underscores that each of us is “W E T C H A L K, / several, probably, WET / CHALKS swimming together” (54). There is no single reading of the self, no need for prolonged introspection, because the construct of “I” is itself understood as a collection of systems. This interplay, this hybridization and amalgamation of perspective — historical, personal, artistic, scientific, and imagined — allows Bedient to name the expansive negative space that exists between the pages, poems, and lines of The Multiple.

“This thing this thing this thing this thing,” Bedient intones as he launches into the recursive routine that closes the book’s opening poem (13). There is no feasible way to name the infinite except through such logical machinery. Bedient happily embraces that limitation from the outset. To insinuate the gestalt of perspective that necessarily ricochets from a singular “I,” these poems strive to make themselves “electric with you, / with you, pronoun so sweet and burning” (81). The inevitable result of Bedient’s inclusive “you” is an endlessly equivocal “I.” When it’s a historical figure, we see ourselves. When it’s an abstraction, we see a community of lovers. When it presents itself as the author, we necessarily suspect fiction. We’re never quite sure who we are.

It isn’t that Bedient eschews personal experience. These poems are littered with the leavings of individual perspective, including some we’re encouraged to suspect might be the author’s own. Even as The Multiple declares poetry of the personal irrelevant, these poems rely on a communal, disjunct slurry of personal particulars as the only available raw material for communicating what Bedient describes as “an impossible totality”[4]. This tension between relativistic gestalt and quantum-mechanical particulars is explicitly addressed in the self-contradicting dialogue of “There are as Many Universes as there are Phrases”:

I can’t stop to explain

every little thing

to you, I no longer

write about the personal,

my theme is the moment

— bottomless, self-

destroying — and anyway

the door of the trailer has

opened she steps down

like a long-legged bird

testing a thawing river,

watches me play,

smiles, turns away. (31)

We can’t know if the particulars on the trailer steps are drawn from the personal experience of the poem’s “I” or not, especially given the speaker’s initial assertion that there will be no personal anecdotes. The second stanza might be read as a contradiction of the purpose outlined in the first. Alternatively, the experiences of the “me” might be read as a distinct offering from an alternate first-person perspective. The “me” and “I” are analogous and autonomous, both self and other.

Throughout the text, this equivocality of perspective establishes smaller systems of internal overlap, which mirror the larger systems established between poems. The Multiple relies on this ongoing ars poetica of contradiction to conjure its expansive landscape of ambiguity. The layout of this poem — twin stanzas arranged in columns that read vertically even as they adhere horizontally — emphasizes that uncertainty. This is personal, but it isn’t anyone’s personal in particular. Or rather, it’s everyone’s personal.

Against this backdrop of all-embracing perspective, “The Gordon Stewart Northcott Murders of Boys in Wineville, California, 1928,” provides an unsettling moorage for the epic fragments that both precede and follow it. The poem, the most distinctly narrative in the text, presents the gruesome particulars of the Wineville Chicken Coop Murders not to shock, but to insist that the totality proposed by The Multiple be taken to its logical conclusion. The interchanging perspectives of both perpetrator and victim are filtered through the second person pronoun “you” by an unidentified, authorial “I.” Bedient’s unflinching amalgamation of this narrative with all other narratives, including his own, emphasizes the depth of the plurality for which he argues. You are innocent; you are culpable; you are Gordon Stewart.

The poem appears on page thirty-three, one third of the way into the text. This central placement allows the presence of the poem to be implied well before it arrives, though its full gravitational pull is only realized retroactively. Over the course of the first thirteen poems, tropes of birds, butchers, axes, and eggs set the stage for this outpouring of terror, violence, and unexpected empathy:

We are suspect men birds earth wrists cuffed

bent over the hood of evening (15)

O doctors of the butcher-shop, the finger-painting on your aprons is

the masterpiece in my chest, I ignore it, I am salty like (21)

It was there that the headless chicken ran, excited with the news,

while your father stood unmanned in the yard

holding the short red skirt of the ax. (22)

Like bees that crawl on an egg hot from a hen’s ass

(they do not know what’s inside

they will kill this thing hot from the hen’s ass), (24)

the wave-shovels cannot pick up the dead duck fucking waves hats off

to the dead duck (26)

The violence in these threads registers immediately, but because the hard-hitting motion of “Gordon Stewart” hasn’t yet arrived, that violence is still situated exclusively within and between the systems of these earlier poems. The butcher, the father holding the ax, and the destructive bees are all positioned within a community struggling to understand this violence as an aspect of itself. If this community feels at times as though it might teeter into the depths, it also tempers that violence with a measure of hopeful resistance.

Once the poem announces itself, this earlier imagery is suddenly rife with unwanted particulars. It’s impossible not to see the unfettered violence of Gordon Stewart nested everywhere within these poems, within ourselves. Rather than allow this realization to drag the text into abject despair, Bedient employs “Gordon Stewart” as a hinge that allows this process of insertion to continue in both directions as the text proceeds. In the second and third sections, these tropes continue to push forward and morph into new threads that reinform not only our understanding of Gordon Stewart, but also the perspectives that precede the poem. The Multiple insists we struggle to integrate even our most disturbing potentials into any understanding of reality we construct.

Like the typographical systems established in the poems’ titles, the new communities that develop in later sections overlap without erasing. In this way, the coop that contains both the chickens and eggs of the first section provides Bedient with the communal prefix “co-” that informs the tenor of the second and third sections:

the sun scratches the tulips out of the dirt

“co-“ that makes sense,

“and” is a sovereign good (50)

The violence of Gordon Stewart doesn’t disappear, but instead is reversed and reapportioned as the book progresses. Here, it’s the physical violence of the sun that coaxes organic bodies from the soil. This isn’t a different violence. It’s the same violence from a new perspective. This communal dissection of the word “coop” continues in the third section with another recursive routine that suggests the word’s resonance with its heteronym “co-op” by repeating it until it begins to dissolve into its component parts (65). It’s no coincidence that the title of the poem where this repetition occurs is the only other to share its typeface with “Gordon Stewart.”

Again and again, The Multiple takes hope and despair on equal footing, enveloping both in its ever-expanding collection of particulars. Bedient rejects the primacy — and authenticity — of individual perspective. These poems embrace community in its totality, violence and all. They argue that acknowledging this totality is the only way to initiate a shift in our relationship to that violence. By acknowledging our communal culpability, we inevitably acknowledge the possibility of our own humanity. The Multiple employs the unlikely figure of Gordon Stewart as a vehicle to demonstrate how such shifts might occur. The bloodied axes, butchers, dressed carcasses, and serial killers of the opening section eventually morph into the scents, breaths, and purrs of the unfettered body calling out for a more hopeful mixture of community and violence: “or why not a moan from far-off sea-sucking clouds? / Why not love?” (76).

1. Calvin Bedient, Candy Necklace (Hanover, NH: University Press of New England, 1997), 48.

2. Bedient, The Violence of Morning (Athens, GA: University of Georgia, 2002), 36.

3. Bedient, Days of Unwilling (Philadelphia: Saturnalia Books, 2008), 4.

4. Bedient, “A Brief Interview with Calvin Bedient,” by Rusty Morrison.