A vital territory

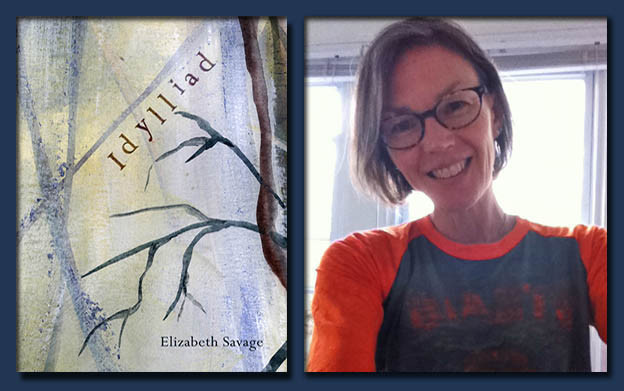

'Idylliad' by Elizabeth Savage

Idylliad

Idylliad

Deborah Poe: In Lyric Postmodernisms, Nathanial Mackey evokes Zukofsky’s lower limit of speech (or “check,” as Mackey refers to it) and upper limit of music in consideration of the lyric. Mackey writes:

Our recent turn toward promoting check over enchantment wants to forget lyric’setymology, as though the art might arrive at a point where there were no strings attached. But strings are always attached, even in the most thoroughgoing doubt or disenchantment.[1]

In Idylliad, Savage engages but inverts the lyric and pastoral, disrupting our expectations of those traditional modes. In doing so, she more deeply engages doubt and (dis)enchantment relative to ideas of property and territory as articulated through poverty and war (the strings).

There are three sections of Idylliad: “Matter,” “Comestibles,” and “Chambers,”modeled more or less explicitly on Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. The book begins in “Matter” — fences, walls, the dogs, a mine, a tree, a floodlight — objects of the everyday in a glistening mundane that turn on an axis of elegy and idyll, beauty and fear.

Poems like “Flood Light” in “Matter”attentively complicate the ordinary:

joined integer

of alien materials

you cannot be a fence

glass & plastic antidote

for the chimney’s

intimate smoke

as the sky

does a dead on mimic

no parody, no sun (18)

In a mathematics of materially strange light, Savage insists that the light itself cannot be a fence. We are told that you — an individual — cannot (should not) be a border. Further, a light as “glass & plastic antidote” is what kind of remedy when “chimney’s / intimate smoke,” rather than offering comfort, delivers poison? There is something similarly unsettling about a sky in its theatrics that imitates with its humorless light.

The second section, “Comestibles,” turns to stuffs of nourishment — this is not just a unidirectional nourishment of humans by way of earth’s resources. Nor is the section an idealistic or essentialist representation of nature. A juniper knows June through its summer juice. Lichen is at the mercy of “ravening fire.” A volcano “at its trigger … breathes by burning / sleeps by seeping” (42). The land is a German layered cake, yet layered with the delight are “sugared disdain” and eruptions from the earth.

Throughout this section, and indeed the entire collection, Savage defies anthropomorphism. She elevates and equalizes offerings from the land and the living, where borders between earth and human being are blurred in their communion.

“Chambers,” the last section of the book, brings us into a meditation of the spatial — chambers of exteriority and interiority. “Territory vs Property” reads:

“Let me recite what history teaches. History teaches.”

Gertrude Stein

East rails into west

where safe belies spent

& the whitetail leaps

over whitewashed fence

& whitewater streams

like a darkened spring

down the desolate face of June

as bodies run in place

floating hats, flowing boots (68)

In this poem that digs into the terms territory and property, one imagines a train running from east to west across a territory, across property lines. The false impression of safety is given off, when what is present is just overused and potentially dangerous land. The deer’s image comes as a relief, its beauty as welcome as its movement over the fence. The natural world, like the manmade trains, traverses across territory and property. The deer, however, does not have to abide by the agenda of tracks and imposed boundaries. The fence the deer clears, moreover, is whitewashed. And the meaning of whitewashed is agitated, given that to whitewash a situation is to prevent people from knowing the truth. Alliteration and repetition in whitewashed and whitewater intensify the music as much as our understanding of the poem. The use of streams, as both noun and verb, multiplies meaning, carrying not only the movement of whitewater but also a vital comparison between movement and stillness in streams and springs. The poem makes you feel the lines of territory and property, as arbitrary as they are real. By the time we’ve swerved to the desolate face of June, the bodies running in place, the hats and boots floating by, we’ve arrived at something ominous. The running bodies evoke soldiers (or miners) pounding the land without progress and perhaps also the thoughtlessness and self-involvement that goes hand in hand with being consumed by boundaries of home and state. What does the fact that personal belongings flow past person-less say about territory and property? The answer might be that we are impacted by what goes on throughout the entire territory even when we are within the periphery of our own dominion.

Ethel Rackin: What first intrigued me about this vexed juxtaposition between territory and property that Deborah addresses is Savage’s uncanny ability to clear breathing room or space, thematically and somatically, in the face of our ever-shifting personal and national boundaries.

And given the book’s title, this clearing of space does clearly hearken back to poetry that comes out of the pastoral tradition, originating with the Idylls by Greek poet Theocritus. The Idylls are most commonly remembered for their focus on an idyllic landscape as the setting for song. However, as Paul Alpers suggests inhis discussion of the singing contest between Thyrsis and an unnamed goatherd in Theocritus’s first idyll, “we will have a far truer idea of pastoral if we take its representative anecdote to be herdsmen and their lives, rather than landscape or idealized nature.”[2]

Savage’s dynamic treatment of the relation between landscape and living subjects is highlighted when we consider poems across sections such as “Path” (from “Matter”) and “Tenement” (from “Chambers”). As Deborah mentions, the collection as a whole meditates on states of exteriority and interiority, enacting a kind of archeology toward an interior.

Path

Everywhere there is a cushion

a spacing invitation

an arm’s breadth exit ramp

caution thrown wide to race

Anywhere there is an angle

measuring a sheet of sky

Somewhere a limit, elsewhere

fine strokes

denote a wind of suspension

of trespassing intention

Thorns will climb stems

thorns will throne leaves

acre over acre of elegy

Elsewhere there is a fastening

a note pinned to your coat

another cyclone centering

suitable for wandering (15)

This poem’s capitalization of indefinite pronouns “Everywhere,” “Anywhere,” “Somewhere” and “Elsewhere” is telling, especially given that “Path” begins the collection. Offering a guide, map, or teleology, “Path” marks off the book’s territory, precisely by calling attention to its expansive immeasurability. As such, the poem offers us a “spacing invitation,” “an arm’s breadth exit ramp” “suitable for wandering.”

However, even as the organic beauty of nature (and the book itself) invites us in, it proffers warnings, of “trespassing intention,” “thorns,” and “another cyclone centering.” So, the path into pastoral is marked as “caution thrown wide” into a fertile and potentially dangerous territory. And while aspects of the landscape of Idylliad are certainly inviting, as they are in the Idylls, persons are continually foregrounded. In particular, Savage focuses her keen attention on the particularities of physical and psychological constriction suffered by those living in a seemingly endless state of poverty, as well as the hardships associated with our seemingly endless state of war. In this regard, the book reaches back to the Iliad as much as it does to the Idyll in “acre over acre of elegy.”

As tempting as it may be to follow nature as metaphor throughout the collection, this would constitute misreading. For nature’s beauty — sublimity even — along with its harshness and dangers, are real to Savage, and made real to us. Just as in early pastoral, the woods are enchanting precisely because they are alive.

This puts me in mind of another contemporary artist who works with nature’s beauty, danger, ephemerality, destructiveness, and connection with human ecology, Andy Goldsworthy. Goldsworthy succinctly characterizes our blindness to beauty’s complexity in his documentary Rivers and Tides: “I think we misread the landscape when we think of it just being pastoral and pretty — there is a darker side to it.”[3]

While Savage’s landscape is, in fact, beautiful, it’s dark besides. As such, Idylliad moves us beyond the notion that the beautiful is merely beautiful, or that beauty is somehow superfluous; rather, beauty itself is always complicated by its own inherent demands and dangers. Savage observes the “coldness” that inheres in much of human experience in poems such as “Tenement”:

no sigh lawning clucks

coo their rote

uncoated

quartered high

by blue

the same question

the same cold

question all day

long put to you (74)

Beginning with a kind of Steinian punning — “no sigh lawning” or no silencing “clucks” or clocks — Savage lands on an anaphoric cold: the “cold” “question” put “all day / long” to those kept in tenements.

Rather than creating a playful lyric repetition, Savage’s lyric enacts the repeated dead end of poverty, centering on the dwelling space as a kind of repository of grief. The rhyming of “coo,” “blue,” and “you” further lyricize that grief by attaching it to the classical personification of a bird. Again, however, lyric is put in service of a trenchant social observation on injustice.So, beauty is complicated at every turn.

Poe: Ethel writes insightfully above of “Savage’s ability to clear breathing room … thematically and somatically, in the face of our ever-shifting personal and national boundaries.” The last poem of the collection, “Canoe,” carves just such a space. Savage witnesses our connection in human experience.

Canoe

In truth, there are two

& the violet-footed

evening their ocean

inverted wishing-pools

emptying washes

without change

slick in the trying rain (78)

Engaging us directly, “in truth,” the speaker tells us there are two, not one. And in that shared experience is a violet carpet. The evening is not just expansive; it is as boundaryless as an ocean. Our gaze turns from public spaces to domestic ones in the same breath, as wishing pools are turned on their heads like a pair of pants brought out of the wash coinless. This world “without change” exists far from a world where industry profits hand over fist from war and where a world without money is a constant struggle. Yet “without change” also expresses dishearteningly that despite all our wishes, some things (e.g. war and poverty) remain the same. Our frustrations with the state of the world are echoed in the rowers’ experience, “slick in the trying rain.”

Yet the title of the poem seems to acknowledge alternatives. In fact, a canoe is a method of transportation that allows humans to cross and recross personal and national boundaries. The collection ends then not in stagnation, not in constriction (and not in formal terms — to use Nathaniel Mackey’s term — phanopoetic snapshot[4]). The collection thus ends in nuanced movement across an unidealized space.

Rackin: In this regard, Savage enacts the root of (dis)enchantment, with which Deborah started our discussion. Not only, as Mackey suggests, are we at risk of forgetting lyric’s etymology, we are equally at risk of forgetting enchantment’s, and in doing so, we may miss the magic influence of poets like Savage.

According to the OED, enchant comes from the French enchante-r and the Latin incantāre, in- upon, against + cantāre to sing; and its first definition is to“exert magical influence upon; to bewitch, lay under a spell” and “also, to endow with magical powers or properties.”[5] In effect, as Deborah suggests, Savage’s lyrics create “nuanced movement across an unidealized space” through lyric’s spellbinding inversions. Take the opening poem of the collection’s final section, “Chambers,” for instance:

Uninsured

Held tight as empty scales

widows & orphans

tip

what’s gone is gone

money burns a hole in its own

wild song (59)

Savage’s short “wild song” is not song for song’s sake; it becomes money’s “own,” complicating the economy of the poem in a Dickinsonian manner. The lyric itself is implicated even as it elucidates and elegizes the black “hole” of late capitalism’s ravages. As a collection of such wild songs, Idylliad reimagines the pastoral idyll to create a vital new territory for the American lyric, heuristically inviting us to commune and connect long after an individual song is over.

1. Nathaniel Mackey in Lyric Postmodernisms, ed. Reginald Shepherd (Denver: Counterpath Press, 2008), 133–134.

2. Paul Alpers, What is Pastoral? (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 1996), 22. My discussion of pastoral is informed by Susan Stewart’s graduate seminar on the subject at Princeton University in 2006.

3. Andy Goldsworthy, Rivers and Tides: Andy Goldsworthy Working with Time, directed by Thomas Riedelsheimer (2001: Mediopolis Film- und Fernsehproduktion).

4. Nathaniel Mackey in Lyric Postmodernisms, 133.

5. “enchant, v.,” Oxford English Dictionary Online (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).