Sound matters

A review of Deborah Meadows's 'Translation, the bass accompaniment'

Translation, the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems

Translation, the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems

“Frequency.”This single-word line begins one of Deborah Meadows’s poems and suggests radio listening as a poetics: an act of receptive agency, tuning in, selecting from a cloth of constant notes, words, thoughts, events, static. Meadows’s Translation, the bass accompaniment: Selected Poems is the sounding of consciousness, but not singular, not just her own: these poems are patterns pulled from texts in order to make a new accompaniment, to expose “the syntax of exploratory thought” (9).

Indeed, in the preface, Meadows identifies her poetics and a whole chorus of influences: “The bass guitar creates patterns that make music into a visceral experience — they are what infect the body” (9). She continues, explaining that the works “are in dialog with other authors, and here, experimental poetry engages logician Quine, encyclopedic novelist Melville, philosophers Irigaray and Deleuze, theologian and synthetic philosopher Aquinas, poets Dragomoschenko, Hejinian, Raworth, Baudelaire, and Celan, Soviet cinematographer Vertov, video artist Bill Viola, and others” (9).

I first heard Deborah Meadows read in 2011. I wrote, then, that I felt I had a lot to learn from her, and this collection solidifies my belief that many of us do. This capstone book looks back on Meadows’s prolific writing life, and I believe that Meadows’s poetry stands out among contemporary experimental poetry in two ways: in her treatment of matter, including political and economic realities, and in her use of and trust in sound. A member of the liberal studies faculty at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, she is not situated in a creative writing department. She is not stringently aligned with any new poetics or movements of the moment, and her inspirations are vast and multidisciplinary. This is all the more reason to tune in to her work.

“Clear the whole”

Translation is comprised of eleven sections, and the first five sections are a through-writing of Moby Dick. In “Invocation,” I read a key to the multichapter sequence: “Clear the whole / Clear where you wrote ‘that and what’” (17). Here is another call to release language from the ideal of “whole” capture, from the possibility to own, where the aural slippage between “whole” and “hole” is also not insignificant: clearing a space in order to receive or take in something new.

These lines imply a beginning again, into compositional practices that challenge authorial control. In “Chapter 110,” Meadows outlines this process: “To copy text from text: a departure / from graphic marks to truths that turn / on poise and difference. Can makers / know sense of their senses?” (56). Her questioning invokes language as sensing where “to know” is to question and not to possess. In “Chapter 126,” Meadows takes the image of the coffin and extends it toward writing itself:

The lid implies body as witness

to cobbling “beneath”

carpenters; dignity balks

at buoyed air, eclipsed signs of late.

His coffin can endure

bedsteads I forgot — no caps

at sea nor job-shop,

stash, or lee. One speaker

displays local pikes abroad.

Novel structure

cyclopic or

encyclopedic? (62)

The lyricism of this passage — notice the internal rhymes — pulls the reader through at a rapid pace. Therefore Meadows enacts the question of this poem via sound, and quite literally via the notion that writers, as “carpenters,” construct reality. Here “novel structure” can be read as referring to the novel as source, but also to the project of making something new, lyrical, constrained, and intensified through poetry.

The poem ends with a question, a bent note, an upward turn, and an “answer” could go either way. In fact, doubt — and it is almost pedagogical to me, in that I am thinking of a teacher’s aim to invite students in to the space of questioning — is invoked throughout Translation.

In the subsequent poem, “Chapter 127,” which begins by taking up the previous poem’s question “On the state of the novel as a coffin,” Meadows once again turns to language as sound intensity:

From cabin to shop, believe in

sufficient music, in caulking

or sounding out the unpronounceable.

Hark, all things come right

with a test upon waters for central

lines, radiant riggings. (63)

Reading this work, I asked myself again and again: to what extent do we trust the ear as able to organize language toward meanings? To study Meadows’s selected works is to research this question.

A poetry of matter/that matters

In such a fluxing field as sound, it may seem that meanings are not easily construed. Meadows is certainly working out of the lineage of Language poetry, with its characteristic indeterminacy and treatment of language as matter, allowing coauthorship between writer and reader. A nondirective space, a space in which meaning is constructed through choice and where language itself is active, is the politics, goes the thinking.

But I do not read Meadows’s works in this light entirely. If she uses found text, it is incorporated to a significant degree, and chance operations are in no way privileged or showcased as a move of clever authorship. Her edges are sharp, her tone and pace are at times desperate; I read clear political intentions, and she is willing to sound the alarm. Simultaneously lyrical and conceptual, Meadows’s work is exemplary among contemporary poetry. In fact, it challenges the clunky, western-world, Cartesian construct that would differentiate between somatic experience and conceptual practice.

The urgency in her work becomes most clear to me in the middle of the book, in the section from Goodbye Tissues. This is one of my favorite books by Meadows, also published by Shearsman in 2009. The “tissues” of the title calls to mind the “soft tissues” of the body, their vulnerability, and at the same time, saying “goodbye tissues” issues a farewell to pathos.

This section begins with “American Possessions,” whose first line is indented, as if a continuation of the title, yet sandwiches nearly a half page of white space — as if there has been a whole other text in between the titling and the beginning of the poem:

far, black lung

knot-spent, gas paltry

decimal, organelle, go?

convey the stepped day

by horn blast, retinal

hinder written or damned

“already”- town. (127)

Here sounding is a way to live inside the body who senses, who listens to the vibrations between words and underneath proclamations.

Many of the sequences gathered in Translation address things that “matter”: political and economic systems impinging on citizen bodies. Meadows’s biography includes that she grew up in Buffalo, New York, in a working-class family, and throughout the book, she engages struggle without romanticizing disenfranchisement, and without relying on narrative witness work. There is something hard fought in her work, as if she is aware of the risk of disconnection with one’s tribe that often accompanies the movement into a poetry of this risk, especially when one simultaneously refuses to suppress firsthand Rust Belt America experience.

For example, in the sequence “Procuratio” from Depleted Burden Down, Meadows intermixes her dissatisfaction with traditional narrative as well as material political realities: “But a substitution theory: the word for the thing, the thing for the other thing, has a ‘universal’ appeal. It’s money. And little in the way of theorizing can interrupt its commerce, its erotic appeal” (163). She continues, issuing either a poetics or a warning, or both: “Haul and scrape good Word for importation to godhead, poached and re-set, spring mechanisms and all. Executed by market track, human capital, finance group, our prize, seminar on human entourage if you have the software, foundlings’ Houdini, erased land, term professor, robot message” (163).

For me the verb “executed,” with its two possible meanings, is the key to Meadows’s complication: is the “good Word” destroyed by market forces? Or is poetry actually made by these same devices? The last line of this passage suggests that the answer is both: “Hard to see the go-between we are” (163).

“voluptuous, but now a recession”

The book’s final sequence, “Lamb Notes,” which Meadows articulates in her introduction as “a poem that hints at a version of tomorrow” (9), is inspired by a lecture given by designers Zoe Coombes and David Boira at SCI-Arc in Los Angeles in 2010. “Lamb Notes” is a sparse sequence, and very delicately Meadows draws a relationship between “lamb” and “lamp.” In those two words, separated only by a more pronounced popping of the lips, Meadows connects Catholicism’s Agnes Dei image and illumination. Meadows’s “lamp, perfection / lamb, order // dirt experiments, less / controlled, more tactile” (231) eventually leads to a final page inscribed with just these lines and an asterisk:

three parts for chopping block

symmetrical paired

handles

voluptuous, but now a recession (234)

I have come to the end of Translation, the bass accompaniment with an overwhelming desire for more poetry: to live inside this world of music, text-making, reading, noticing, and delicate strength.

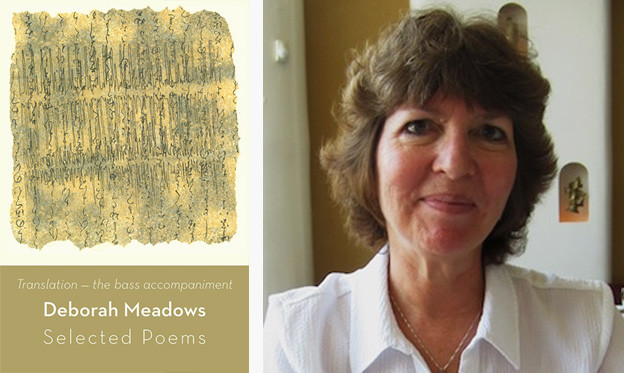

If elsewhere in this volume Meadows has asked, “When did coherence displace constancy, meaning unseat duration?” (89), she answers with the book’s cover image, a print by Meadows herself entitled “Nightingale Sound Print, Heart Sound Print Over Ancient Calligraphy” and on the book’s final page—

“voluptuous, but now a recession” (234)

Beautifully excessive matter and desire, at times temporally withdrawn — receding — remain imprinted despite exposures to surrounding regimes of the rational. Deborah Meadows’s poetry is for this awareness.