The products of labor

A review of 'lo terciario/the tertiary'

lo terciario/the tertiary

lo terciario/the tertiary

los productos del trabajo tienen sus residuos.

a estos residuos les llamamos objetividad espectral.

a esta objetividad espectral le llamamos mera gelatina.

a esta mera gelatina le llamamos

cristalizaciones de la sustancia social común.

a estas cristalizaciones les llamamos valor.[1]

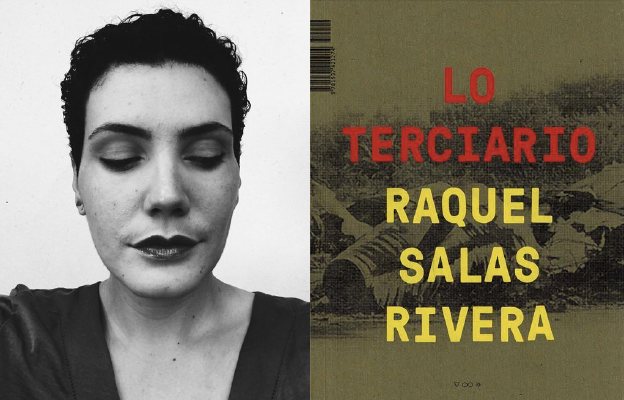

So begins “todas sus propiedades sensibles se han esfumado,” the opening poem of lo terciario/the tertiary, the newest collection released in May by Puerto Rican poet and translator Raquel Salas Rivera. Or it begins:

the products of labor have their residues.

we call these residues spectral objectivity.

we call this spectral objectivity mere gelatin.

we call this mere gelatin crystallizations of the common social substance.

we call these crystallizations value (12).

Titles such as “todas sus propiedades sensibles se han esfumado” / “all their sensible properties have blended away,” as with all poem titles in the collection, are lines drawn from Pedro Scaron’s El Capital (Siglo Veintiuno Editores), a 1976 Spanish translation of Karl Marx’s Capital. Whether we receive Scaron’s translation in translation, and whether we read Salas Rivera’s lyric appraisals of Marxist social theory — by turns didactic and personal, caustic and intimate — in Spanish or in English depends on how the book lies in one’s hands. Constructed in the tradition of dos-à-dos or tête-bêche binding, the edition has two front covers: lo terciario and the tertiary. The Spanish and English texts are rotated 180° relative to one another, such that the bilingual reader, halfway in, would rotate the book upside down to read the collection in its entirety. Or — if you are an anglophone reader, like myself — you are made literally aware that you are reading only one half of the book.

The unique design of the book introduces some of the most central claims of lo terciario/the tertiary. First, it is attentive to its own status as an object, or commoditized “product of labor [and its] residue.” The acknowledgments and printer’s blanks do not appear as front or back matter, but squarely in the middle of the book’s pages, dividing its two sections; typical back cover anatomy — namely, the product barcode — is emblazoned on the spine. Poetry “crystallizes” as its “residue.” Secondly, despite lo terciario/the tertiary’s patent work in translation, perhaps its most immediate and material claim is that it is not “a work in translation.” That we are reading Spanish translations of English poems — or English translations of Spanish poems — is an assumption the book physically rejects.

This is a provocative claim, and a surprising one. At readings, Salas Rivera reads their poems in Spanish and subsequently in English. In multiple interviews, Salas Rivera has described Spanish as primary to their writing process — they write in Spanish first, then translate their poems into English. (In a recent conversation with Salas Rivera, they noted that lately they have been composing in English first more frequently.) In this sense, lo terciario/the tertiary’s egalitarian design seems to have anticipated the complex representational politics that Salas Rivera recently assumed as a civic figure in the United States. Around the time that the collection went to press at Timeless, Infinite Light, in fall 2017, Salas Rivera was selected as the fourth poet laureate of the city of Philadelphia. In this capacity, they identify as “a Puerto Rican and Philadelphian.”

As a fellow Philadelphian, it is difficult to read lo terciario/the tertiary outside of the context of its author’s role as poet laureate. Salas Rivera was inaugurated as the city’s poet at the Free Library of Philadelphia on January 8, 2018, four months before its release. The office has a short history — Salas Rivera is preceded by Sonia Sanchez (2012–13), Frank Sherlock (2014–15), and Yolanda Wisher (2016–2017), and the office is the only civic title for a poet in the state. (The poet laureateship of the state of Pennsylvania established in 1993, meanwhile, saw only one state poet, Robert Hazo. When he was unceremoniously relieved of the office in 2003, the position was effectively terminated.) Concurrent with Salas Rivera’s term, the city of Philadelphia poet laureate program moved under the auspices of the Free Library’s new Center for Public Life.

Salas Rivera read multiple poems from lo terciario/the tertiary at the inauguration ceremony. Most notably, they read what I would suggest is one of the defining poems of the collection, “no se cambia una chaqueta por una chaqueta” / “coats are not exchanged for coats,” in which we are asked, as if students, “to examine two commodities.” Let’s take, for instance — for the purposes of this lesson, the slyly didactic tone of our teacher suggests — “50 years of work and one debt / accumulated over 50 years”:

as proprietor of the first

you decide to take it to caribe hilton banking

where i offer my life to pay this debt.

but they explain that it’s not enough:

just as the debt and the fifty years of work have use-values that are qualitatively different, so are the two forms of labor that produce them: that of the investor and that of the colonized. your life is not enough. you will have to pay with the labor of your children and your children’s children. (20)

The line at the bank, we quickly learn, is a lineage. The second-person speaker will return to it repeatedly, in one instance offering “handfuls of whatever: gasoline station umbrellas, limestone / birth certificates, shutdown shops, / etc. etc. etc.” Finally, “you go to philadelphia / to look for the coats much needed” in order to pay the debt of “your island”:

you work hard, look for a license with a renewed address,

buy three four five hundred coats,

go to the local branch and say

here they are.

i would like to pay that debt.

but without looking up they answer

here in philly we don’t accept coats. (22–23)

Throughout the collection, too, we learn more about debts than inheritances. lo terciario/the tertiary places itself in a political lineage rather than a poetic one. More invested in an activist community than a literary tradition, its most obvious influences are the characters that actively populate the poems and acknowledgments — fellow poets and political organizers, family members, lovers; and finally, “carlitos.”

“Carlitos,” as Salas Rivera calls Karl Marx, in a mordant term of endearment, becomes a through-line in a broken family tree — one interrupted by colonialism, geographical distance, linguistic difference, and traumas both historical and present. He is an inescapable father figure the author treats in kind with the sort of punitive affection they suppose they were given. “i remember the first time i read marx, i wanted to be marx and also wanted him to like me,” concludes “first phase: the capitalist appears as a buyer” (39). To Salas Rivera, “that was the most important thing: that carlitos like me.” These lines, like so many other moments in this collection, mediate confessional intimacy with bitter humor. As a reading of Marx, and the leftist political formation programs in Puerto Rico that were animated by Scaron’s translation of Marx, the collection is critical and irreverent. But it also sees them as valuable and urgent resources: lo terciario/the tertiary, more immediate than a theoretical meditation, was written largely in 2016 as an aggrieved response to the Puerto Rican bond devaluation crisis and the controversial Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability Act (PROMESA) Bill, passed July 1 of that year.

As Philadelphia’s poet laureate, Salas Rivera has extended the political vision of lo terciario/the tertiary — most recently organizing, in collaboration with poets Ashley Davis, Kirwyn Sutherland, and Raena Shirali, the 2018 summer poetry festival We (Too) Are Philly. Taking its name from Langston Hughes’s famous poem “I, Too,” the festival hosted “a line-up of poets of color who have a strong commitment to fighting white supremacy and collaborating with local communities to create shared creative spaces.” Each event featured a poet from Philadelphia and at least one poet who writes in multiple languages. Much as lo terciario/the tertiary is a response to PROMESA, the festival is a response to “ICE and fascism,” celebrating — and insisting on — Philadelphia’s status as a sanctuary city.

Both lo terciario/the tertiary and We (Too) Are Philly respond to the unwritten racist policies that govern poetry communities. Just as the white anglophone reader of lo terciario/the tertiary is made conscious of themselves as a consumer of a product of labor, “We (Too)” attends to questions of audience. It is not enough for a poetry reading to boast a diverse lineup, the mission statement asserts: “We aspire to have not just poets of color performing, but also POC audiences.” This is a poetics that seeks to disrupt “the racial power dynamic in poetry communities in which white audiences consume black and brown art.”

Salas Rivera’s lo terciario/the tertiary (which was longlisted for a National Book Award) is as compelling a lyric sequence as it is a timely manifesto. But another of its chief successes is as a part of the dynamic and ongoing poetic program of Philadelphia’s poet laureate. This collection by the city’s representative poet suggests that tokenizing brands of representational poetics — programs that allege to hail diverse voices without structurally engaging their communities — are over, at least for now. If Salas Rivera’s work is not to be missed (and it isn’t), so too are the voices of We (Too), including Warren C. Longmire, Porsha Olayiwola, Cortney Lamar Charleston, and Philadelphia’s preeminent outgoing youth poet laureate, Husnaa Hashim.

1. Raquel Salas Rivera, lo terciario/the tertiary (Oakland, CA: Timeless, Infinite Light, 2018), 12.