The point of contact they create

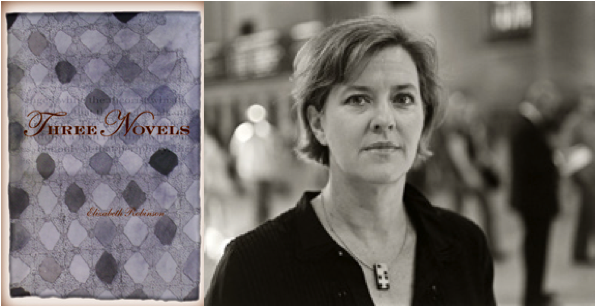

A review of 'Three Novels'

Three Novels

Three Novels

Elizabeth’s Robinson new book Three Novels engages with an archaic form, in this case the Victorian novel. In particular, Eve’s Ransom by George Gissing, and Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone and Woman in White, the latter two read to her as a child by her father, the former a book they shared as adult readers. In Kathleen Biddick’s book The Shock of Medievalism, playing off Freud’s essay “Mourning and Melancholia,” she writes:

Trauma … resists representation since its traces recur fragmentarily in flashbacks, nightmares, and other repetitive phenomena. Past and present symptomatically fuse in such repetition, and, in so doing, the possibility of futurity — change — is foreclosed. Such fusing is typical of melancholy. To unfuse past, present, and future, to return to the narrative relation of temporality, requires the work of mourning. Mourning does not find the lost object; it acknowledges its loss, thus suffering the lost object to be lost while maintaining a narrative connection to it. (10)

This, in a book that sets out to historicize the institutionalization of medieval studies during the nineteenth century; germane here, though, because Robinson’s is very much a book that responds to trauma — the death of her father, with whom she first shared the above-mentioned novels — and hence a work of mourning. Further, there is clearly a sense of mourning about those novels as well: the lost world they reflect, the possibilities for eros and expression they offer. Which is not to say that Robinson channels some kind of nostalgia for her own childhood and a soft-lens Victorianism; one of the driving impulses of the book is to explore and confront the constraints of that era, especially those faced by the women depicted in the novels. As such — and here, finally, is the primary attraction of the book and its most difficult problem — these poems engage with the Victorian fascination with surfaces (manners, etiquette, decoration) and the obstacles these throw in the way of emotional contact. But also, finally, the way surface itself is the locus of contact.

The first “novel” consists of short prose blocks, and sets forth the issue of loss immediately:

Origin Myth

It has been said that the detective story has structural elegance because it begins with a murder and unravels neatly backwards to relate the cause of the murder: a solution. But this was not true of the first detective story. That story entailed no murders, only a loss, various losses.

Other lines focus with elegant lyric poignancy on those surfaces: “The eye flies over the naked body, yes, but sees only skin … the ability to read the skin, its legend of flush and pallor. The true body, the one which, despite all its acumen, cannot get away” (“Surface,” 22). Later, in a piece called “Sleepwalking”: “The purpose is to walk over the very surface of sleep, as Christ walked over the surface of water” (25). But there is, haunting this, a sense of loss and something underneath. “Think of the self as a locket in which one must carry something foul: a secret innocence” (“Pariah,” 27). The final line of this first section captures the tension at the heart of Victorianism (at least in my admittedly limited experience of it): “As the somnambulant gropes towards the site of loss, his beloved looks on in polite and silent bliss” (“Decorum,” 30).

This is beautiful. The first section of the book proceeds as almost an ekphrasis of the moods, themes, and language of the Victorian source novel. At its best, when most sensual, it hints at the lapse or loss between bodies, their unwillingness or inability to connect. The second section is laid out in sparser, fragmentary, lineated poems, while the third seems a hybrid of the two.

A good deal of the book feels like an extrapolation or extraction from the source text, a dance alongside it, an effort to understand its alien discourse of manners and indirectness, which seems a particularly poignant way of reflecting on the mourning that lurks beneath the poems’ own surface. A sense of bafflement pervades: at bodies, loss of bodies, the way that Victorian avoidance of contact can paradoxically bring bodies closer. (It is perhaps no coincidence, and something worthy of study, that the “shock” of medievalism emerges alongside the shock of Freudianism during the Victorian era.) Poetry, especially in the hands of someone as accomplished as Robinson, is the perfect instrument with which to explore this bafflement, this mourning, this loss, and also to hint at the era’s stunning emergences.

Ultimately, there is a satisfying lack of closure here that reflects what Robinson-as-reader notes in her source texts. If the dark harmonies are resolved at all, it’s on the level of language, where Robinson continues to prove herself a poet of some power in manipulating sound, image, and text. Examples abound; one chosen at random reads,

The blanket crocheted itself over the sloping plain, and all

was woolly and opaque Not to be perturbed Portent’s

sharp consonant softened to omen (44)

The resolution of vowel sounds in the final line, already deftly hinted at in the preceding lines, is expert, and the fact that it falls against the “sharp consonant” sounds sprinkled among them is evidence of the level of sonic awareness that Robinson brings to the task, the way that sound can slide into sense and vice versa. It is powerful stuff. If anything, I found myself yearning for more power in a different way — poems that hit with the force of death, loss of time, age, movement. In that sense, there is a poise or even stasis in some of the poems, perhaps caught up too much from the tone of the Victorian novels. But perhaps this feeling is the very lack that the poems, taken altogether, crystallize around, the point of contact they create.