Infidel poetics

A review of John Mateer's 'Unbelievers'

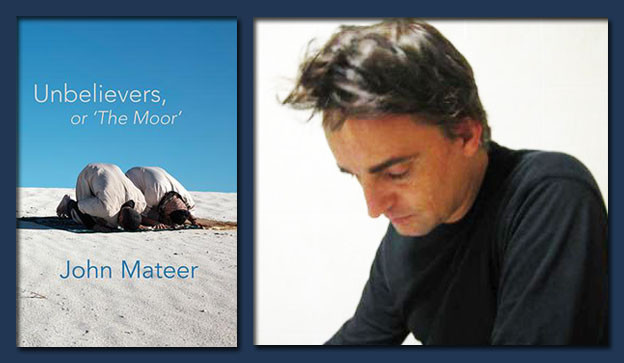

Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’

Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’

Reading John Mateer’s recent collection of poems, we experience a pleasantly alienating affect of suspension from emotional involvement, political certainties, and location. At the same time, Unbelievers, or ‘The Moor’ is dominated by the condition of its speaker — a discursive, self-reflexive persona, which has been continuous throughout Mateer’s poetic oeuvre.

This voice is a shape-shifting entity that, poem by poem, turns to face or even walk right through itself. In Unbelievers it represents Mateer’s own South African youth and his immigrant life in Australia, from the perspective of a poet as well as a traveler. Wandering the region of Iberia, he cuts across time and place to seek possible, alternative, and imagined histories of Western imperial expansion and formation.

Mateer’s tone has a certain wistfulness that will be familiar to readers of his previous work. However, as new readers will find, its note is not self-pitying: Mateer boldly wields irony and elliptical techniques in order to abbreviate or undercut his work’s ongoing meditation upon postcolonial and exile identity. His truth-seeking is frequently thwarted, as in the poem “For Ibn Battuta.” Its cropped brevity and alternating indentation suggest a sense of the speaker’s drift:

I have sought

your Spirit here in scorching

Andalusia. But only found

those memories

of my travels, that

Shunyata. (10)

The poem ends upon the Taoist-Buddhist concept of shunyata or emptiness-openness; a concept that defies lyric neatness. A similarly ironic space is created in the sequence, “The Andalusian Poet,” in which the persona of “the Poet” might refer to the Andalusian poet Federico García Lorca, to Mateer himself, or to both:

That poem

of his

landscape

is yours

and mine.

Whose voice? (15)

To this open end, Unbelievers may be the most structurally fragmented of Mateer’s books to date. It is broken into numerous parts, each split again into sequences of varying lengths and procedural sections that both observe and defy their divisions. A shattered sequence, “The Language” is a particularly beautiful instance of this fluidity. In his afterword to the collection, “Echolalia, or an Interview with a Ghost,” Mateer describes this structural approach as rendering something like shunyata. He suggests that these poems take a similar lesson from Persian painting: “much like miniatures, and this prevents the poems from becoming statements, enactments, embodiments. I don’t want to be in the situation where I ‘proclaim’” (154). His poems embody the nature of identity: an appearance of composition that masks multiple and sometimes discordant realities.

Exploring the first rumblings of Western empire through to its ruins, Unbelievers uses poetry as a necessary site of diversion from monoculturalism. Mateer illuminates overlaps between Western and Eastern traditions — seemingly aberrant moments that are closer to cultural identity as we live it than as we proclaim it. He inserts himself into history, as in the symbolically erotic role-play of “The Moor,” and into graffiti, epigraph, and painting: drawing unexpected analogies between landscapes and bodies. He glimpses his doppelgänger, scattered around Europe and Africa like reflective shards; and his ongoing address to the “Beloved” makes a teasingly ambiguous reference to both the female object of the troubadour tradition and Rumi’s eroticization of the divine object.

Mateer may not be interested in making either a lyric salve or a didactic rant, but he is invested in a poetics of peace, in his words, “to rid my language of violence” (148). For example, in “On the Statue,” one cultural ritual threatens to repeat the violence of another:

When in the Cathedral at Santiago de Compostela I will be invited

to hug, for good luck, the marble torso of the Saint,

I won’t. Not for moral reasons.

Embracing someone from behind like that

reminds me too much of how, in the Apartheid army,

we were taught to approach the enemy,

to slit the throat. (13)

The poem’s future tense, however, turns toward the hopefulness of individual agency in contrast to the dictated collective action of the “Apartheid army.” Furthermore, in the succeeding poem, Mateer demonstrates his interest not only in juxtaposing cultural imagery but also in pacifying conditioned expression through the un/translation, research, and visitation of languages. The poem, “(Kaffir),” is named for the abusive term used under Apartheid and that morphed from the Arabic term for unbelievers of the Qur’an. Below its title, the poem consists of only one word: Mirror. Mateer effects an astonishingly simple reversal of etymology, to signify sameness rather than segregation.

It’s important to emphasize that, through Mateer’s constant recognition of emptiness-openness, Unbelievers avoids twee universalism. It tries, instead, to interrupt what he calls “hypnotic” uses of power (156) — a description that calls to mind Jennifer Maiden’s similar intention in her so-called “parallel poems.” Maiden is a powerful comparison with Mateer, in fact: their poetries construct ironic self-mythologies to discuss public affairs; and both poets are time-travelers, drawing continuums between global history and our immediate present in the West. Like Maiden, Mateer is a poetic poltergeist, radically intervening in the living world and possessing the dead with voice and gesture.

There is much talk of ghosts in Unbelievers, a presence Mateer alluded to in a symposium at the University of Western Sydney in September 2013, where he raised the possibility for poetry to access a “spirit world.” We might understand this notion — metaphorically and/or literally — as defining what poetry offers to a culture of migrants, postcolonials, postnationals, and borrowers. This is art for a condition in which our state-defined mythologies fail to express the complexity of our cultural realities. It is not an easy kind of authenticity: Mateer’s poetry struggles with subthemes of permanent loss, confusion and loneliness. Its expression, however, creates a liminal space that does not belong to classic identifiers of nation, language, or locality. Mateer exploits this possibility in Unbelievers, inviting his reader to dwell in un-belonging.