An identity in relation

Anne Tardos on absence

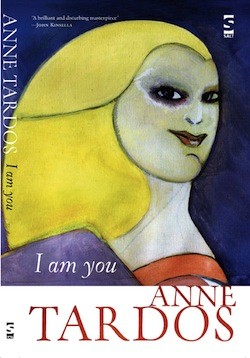

I Am You

I Am You

Grief is the most deeply personal condition, and yet it is also the most universal, extending even beyond human experience to the animal kingdom. To write out of grief is equally to find a way out of it. In the curious case of Anne Tardos’s I Am You, it is also to affirm loss as foundational, or rather to affirm that there is no foundation, to affirm that the removal of the other by whom one’s life has been shaped and sustained reveals an emptiness at the very root of existence.

As the Buddhists say, there is no foundation, but something is always given. Or as Anne Tardos writes: “I try and make good use of what life throws at me” (83).

I Am You is not so much a tale of grief as it is a record of the process of emergence from grief into new life. Tardos writes:

At first it’s the death you need to deal with

That incomprehensible act

It’s all fine and good for you to be dead, but how am I going to carry you about? (87)

In a series of outbursts — cantankerous, humorous, loving, detached, foolish — Tardos delineates her experience of a return to life three years after the death of her husband, the poet Jackson Mac Low. Each statement is surrounded by white space — on the page, in time, of the mind — a blankness that gives birth to the occasion of the present moment and then withdraws it just as fast as the eye follows, the voice changes, and the hand turns the page. The pain of lack gives birth to form as possibility:

We need oblivion to escape oblivion

We need plants around us, and large pockets of time

wherein nothing much happens

Then maybe something can happen. (5)

In “Letting Go: A Poem in 100 Parts,” Tardos explains her method up front:

Each page is connected to the next by the

initial appearance of the phrase or concept

of “letting go,” in its various forms.

The rest of the page is free.

(2007)

For M. (31)

In her perceptive introduction to I Am You, Marie Buck notes the inferred collapse of “For M” into “form” (xiii). The formal constraint of “Letting Go” is a framework for the free play of ideas. Yet the greater boundary between life and death pulls at the writing, forcing it up against the limits of language again and again. Written out of crisis, the work bears the undeniable mark of necessity.

The sudden, permanent absence of the other causes the self to bleed into the recently vacated space — “I am you” — and form a new, hybrid personality. Hybridity feels monstrous. The image of the monster permeates the text:

The monster husband takes my hand

And it feels right (40)

[. . . . . . . . . . . . .]

Intense and prolonged anticipation will either let go of the monster husband’s hand

Or tighten its grip around it and perhaps frighten it (42)

Fear of monsters is common in young children. The loss of the other reduces the subject to a childlike emotional state. The hybrid speaks; the self experiences expression as originating in the other:

What did you just say? I could hear your voice, but couldn’t get the words (56)

Loneliness feels bottomless:

No amount of letting go seems enough (64)

There is, no doubt, a confessional aspect of this work, as Tardos plumbs the depths of despair and longing in ways that are at times almost sensationally personal. Yet this is not your garden-variety, 50s–60s confessionalism, for it is couched within the contexts of process-based, art-making practice and clear-headed philosophical inquiry by a multilingual pan-European-American performance poet of considerable accomplishment. The rapid alternation of spontaneous wit, philosophical depth, and emotional plaint create a platform upon which the truth of the condition of the writing is felt all the more directly, more starkly than if it were expressed solely in the confessional mode, which can so easily become overbearing. Here, by contrast, the reader is respectfully permitted a certain distance that allows the text to breathe like the living thing it actually is.

The result is a kind of philosophical investigation into the multiplicity of time: “Everything rotates around the enormous struggle it is / to get from one moment to the next” (77). When death puts an end to life, it feels to the survivor like a cutting-off — “a breach … a rupture” — that is replicated in fractal by the discontinuous succession of moment-to-moment existence. Alternately, by an act of abstraction the perception of time collapses in on itself:

The moment lets go of the moment and suddenly past present and future are all one (43)

The poet/reader hurtles forward in time. The poem traces the vicissitudes of its own trajectory.

Will I let go of this poem and move on to another one?

Why should I?

Is there something wrong with this poem?

Self-reference is usually frowned upon.

So be it.

I’ll go to a hundred.

Then I’ll stop.

Stop what?

This.

And what is this?

I have no idea.

Words fly like bullets tonight.

I shoot myself in the foot with them.

I try and make good use of what life throws at me. (83)

It occurs to me that I Am You is at once both a loving tribute to Jackson Mac Low the man and an act of liberation from Mac Low’s poetics. Jackson’s work is an epitome of adherence to method, in his case the myriad strategies and processes by which he generated his poems and performances. Fundamental to his poetics was a rejection of self-expression as a model for art-making. This scrupulous stance was based in the rich variety of his studies — Aristotelian logic, Buddhism, anarchism, Kurt Schwitters, John Cage, the Living Theater, Fluxus, Language writing, you name it. Central to his practice was the elimination of the ego as primary determinant.

Of course, Mac Low’s remarkable career, the consistency of his focus and dedication, the prolific output and continuous inventiveness despite all odds of economy and cultural hegemony, would not have been possible without the driving force of a powerful ego. In I Am You, Anne Tardos seems to be trying out proscribed forms of expression in an almost violent transgression of her uniquely intimate education.

I feel I’m getting into a mess by coming out into the open

By coming out into the open, I find myself ever more unsure and vulnerable (86)

I Am You reminds us of something we know but often forget: that identity is formed in relation to others. This truth is more than human; we see it everywhere in the animal kingdom. Sprinkled throughout the text are loving photo images of selected primates — hanging out, bathing, or playing, often with playmates or family. If identity is formed in relationship, what happens when one’s soul mate is suddenly removed from the scene? Who is one now? One possible answer is: “I am you,” where one feels oneself to house the reverberations of the absent other.

Tardos does not shy away from even the strongest, most difficult emotions as she acts out her relationship with her departed husband in terms so visceral that we are almost convinced of his living presence. That is, she insists on examining precisely that which is most unresolved between them — issues of dominance, sexuality, ego, perversion, impotence, poverty, aging, anger, and fear. The tension created through such insistence is relieved periodically by moments of peace in which all is suddenly, albeit provisionally, well.

The crisis seems to be over — for now (178)

Along the way, we get glimpses of a life lived: parental advice, a suicide averted, a memorable handshake, a Django-triggered outburst of love, the life and death of a cat. The final page is a riot: a perfectly compressed pitch of ironic hostility and wistful acceptance. Given its heavy subject matter, I Am You displays a surprisingly light touch. It is inspiringly quick-witted work, the kind that takes courage to write and gives courage to live.

Note: An earlier version of this review first appeared in American Book Review 31.3 (March/April 2010) and is reproduced in Jacket2 with permission.