Hers to elegize

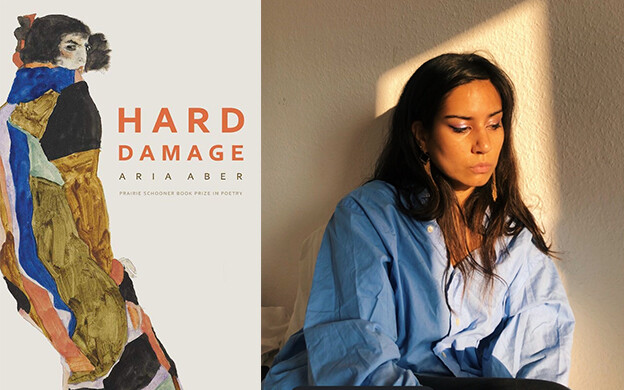

Aria Aber's 'Hard Damage'

Hard Damage

Hard Damage

“Not yours to elegize,”[1] instructs a relative in Aria Aber’s debut volume of poems, Hard Damage. However, Aber’s Prairie Schooner Prize–winning book could be read as an attempt to mourn those losses from which the consoling voice seeks to redirect her. Aber is the child of Afghan refugees who was raised in Germany and educated, in part, in the United States. Her poems in Hard Damage wrestle with the challenge of writing of a place and a political crisis that she neither lived through nor witnessed, but whose presence remains central in her life through traumatized relatives, news of the seemingly perpetual war in Afghanistan, and her own longing for a home where she has never set foot. As Aber intertwines depictions of the present-day conflict in Afghanistan with longer histories of violence, diasporic familial elegy emerges as a form of historical inquiry necessary to understand the reach of contemporary global conflict. At a moment in which the possibility of complete withdrawal of US troops from Afghanistan floats on the horizon, Hard Damage reminds us how the consequences of war persist long past peace talks and armistices.

I find Aber’s debut astonishing, not only for the conceptual difficulty of the poetic position from which she writes about war, but also for her efforts to grapple with the role of beauty amidst terror (here I allude to a poem by Rilke that serves both as one of Aber’s epigraphs and the subject of her lyric essay “Rilke and I”). In “Azalea Azalea” the speaker expresses a desire to devote herself to beauty, ideas, and pleasure instead of death: “This is what I want // to excel in: gardens, elixirs of thought, / no one draping the stench of severed limbs, / yet the catacomb hymns for me” (12). News of an enormous bomb dropped in Afghanistan intrudes on the speaker’s desires, shuttling her consciousness back and forth between attention to suffering and a drive to escape into the sensory or the aesthetic:

How much

of my yearly tax is spent to bomb

the dirt that birthed me? is a question

I never wanted to consider. Let’s fuck

while a farm in Nangarhar erupts

with dead cows — bodies — oh, the flies …

No — what I need to know is how to say non-nuclear

without having to say azalea, azalea, azalea. (12–13)

As Aber considers how her relationship to the nation-state renders her complicit in perpetuating her own familial trauma, she seeks a way to be attentive to these painful contradictions. Over the course of the poem, she learns to face terror without blocking it with beauty. The chant-like repetition of “azalea” in the final quoted line dramatizes an effort to drown knowledge of war in an image of beauty. By titling her own poem with only two repetitions of the flower’s name, Aber suggests that she partially breaks herself of this escapist need. Still, what remains central over the course of Aber’s volume is how beauty and terror so easily elide into each other from the perspective of the home front: “Oh, what wonder to be alive and see / my father’s footprints in his sister’s garden. / He’s furiously scissoring the hyacinths, / saying all the time when the tele-researcher asks him / How often do you think your life / is a mistake?” (14).

Hard Damage centers on two politically and aesthetically ambitious sequences. As with so many of the poets whose influence she acknowledges (C.D. Wright, Muriel Rukeyser, Solmaz Sharif, and even Rainer Maria Rilke), Aber develops her themes through both brief poems as well as longer and hybrid forms. The allusions to Rilke throughout the beginning of the volume crystalize in a lyric essay that uses the writer’s relationship with Rilke to meditate on agency, poetry, wartime, and the force of language. In doing so, Aber articulates a relationship with Rilke that allows her to honor “his urge toward the original you, the you of God, the spiritual you” without turning away from the world (54). Beautifully and intelligently, Aber analyzes the different possibilities inherent in English and in German. She observes how linguistic norms affect how we interpret political events. Describing her mother’s past as a political prisoner in tandem with a study of the demand to use the active voice in English, Aber writes: “What my mother could’ve said: They put me into prison. // What she meant: something has happened to me; that something is screaming inside of ‘my I’” (50). Breaking the norms of English usage by putting “they” in the subject position instead of “I” emphasizes how individuals are formed, sometimes violently, by forces outside themselves. Yet poetry allows Aber a space of some agency, a place where she can revise Rilke’s famous statement about beauty and terror into a new formulation that forces the poet to take greater responsibility: “But what if I said: I let everything happen to you: Beauty and Terror? What if I took the accountability for what happens to you, what then?” (50).

The fruit of Aber’s searching questioning about the role of poetry in times of war ripens in her poetic sequence “Operation Cyclone.” The title refers to the covert involvement of the United States in instigating Afghan regime change in the late 1970s and 1980s (including the now-infamous training of Osama bin Laden). Interweaving historical research, family stories, and self-reflexive portraits of the writer, Aber depicts the lasting effects of a chapter of history that was intended to stay unrepresentable. Talking back to power with remarkable authority, Aber writes: “This war, say the historians, was hidden, / Hidden, but from whom?” (69). She is at her most affecting when writing about men who have gone missing and the subsequent funerals without bodies:

The day they buried into earth

the thing without the body,

all the apple blossoms, I heard, floated

back into the gaunt arms of trees,

the petals curling

into buds tight as fists. (70)

The impossible image of fallen petals reconstituting themselves as buds dramatizes the futile but necessary wish underlying this mourning practice. Similarly, Aber does not exhibit a naïve faith that awakening her audience to the suffering of others will lead to political change. Aber concludes the penultimate poem of this sequence, “Catalogue of Grief,” with a direct address to her American audience: “you couldn’t have saved him, you couldn’t have done a thing // you can’t imagine what happened / you who cannot read from right to left / you who were not there when they took him” (83). Aber confronts us with our own passivity — not to wake us from it but to demonstrate the impossibility of achieving agency across the globe.

Which brings us back to poetry. Meditating on how a family copes with such traumatic loss, Aber writes: “And the living did // what they do: they tasked themselves with the cruelty of song, with braiding / questions they don’t have // the stomach to hear answers to” (84). Mourning emerges as a way not to cope with any individual loss but as a mode of reckoning with the simple fact of being alive amidst so much suffering. By attuning song to terror, Aber casts herself as an elegist for a catastrophe that is indeed hers to elegize. And as the list of US covert operations that surrounds “Operation Cyclone” informs readers of a history of American involvement in regime change across the world — from Syria and Albania in the 1940s to Yugoslavia and Syria again in the 2000s — she insists that these losses are not only hers to elegize but also ours.

1. Aria Aber, Hard Damage (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2019), 15.