Disambiguating rape culture

Lynn Melnick’s nouns

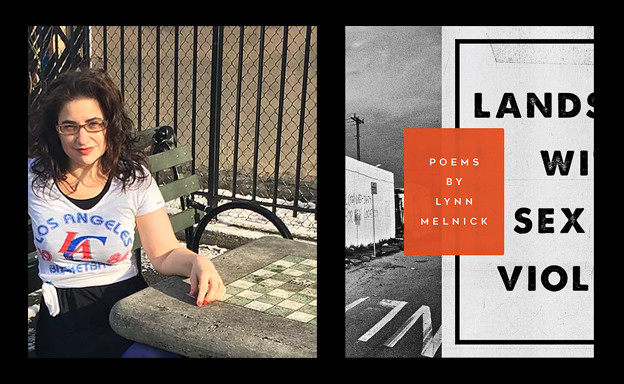

Landscape with Sex and Violence

Landscape with Sex and Violence

Gertrude Stein never trusted nouns. She was wary of their tendency to fossilize meaning, even as she relished their potential to be magnetized: “Poetry is concerned with using with abusing, with losing with wanting, with denying with avoiding with adoring with replacing the noun.”[1] Lynn Melnick’s Landscape with Sex and Violence, eighty years later, takes up this ambivalent and vexed embrace of nouns in the space of rape culture, where adoring and wanting cross use and abuse as matters graver than grammatical concern. Melnick’s poems are built on nouns, structured by and populated with them. Exactly half of the book’s thirty-four poems are titled “Landscape with [Noun] and [Noun],” a formula that offers nouns as pillars, poles of articulation around which the speakers examine the self as thing and things in themselves. The pairs are riveting, evocative compounds — smut and pavement, rum and implosion, wonder and blowback — and the objects that litter these landscapes appear in crisp focus. “Landscape with Greyhound and Greasewood” pairs the ubiquitous shrub of the chaparral biome with the fugitive animal and iconic trademark of American transit. “Landscape with Fangs and Seaweed” pairs menace and predation with marine detritus and dissolution. These poems open linguistic fields where person, place, and thing — handled and mishandled objects, including objectified persons — evoke scenarios that imperil lives: “Biography ungags me / then saws the scene in half.”[2]

Building the poems on nouns allows sharp glimpses of the lived experience of rape culture from the point of view — the eye level — of victim, witness, and ally. The noun pairs in the titles set the scenes, and they also resonate with vocal harmonies that are the source of their lyric strength. The open vowels of “loanword and solstice,” for example, sound ominous tones from the start of a harrowing account. The clicked c’s of “clinic and oracle” carry a crisis into its corrective. Most critics have overlooked how much plush, ludic, lexical romping there is in this book that examines such a serious subject. There is alliterative buoyancy in spite of foreboding in “fog and fencepost,” “blood and boondocks,” and “citrus and centuries” — this last a poem where the nouns we traverse in the landscape are “Farmland and farmland and splendor” (17). We’re in California, we’re in a sound cloud, and we’re in trouble: how can a poet write about something systemic, the misogyny and violence that undergird these scenes, if it is as pervasive as the oxygen that enables her to speak? Melnick finds ways to write about rape, sex work, abortion, and abuse through tactility, through noun-centered descriptions in contexts that include “In the champagne buckets, / spoiling milk” (20) and “one lamp-heated burger” (67). No one who reads this book will forget the rest stop receipts lining blood-stained panties, or the carpet fibers on the tongue.

Melnick’s nouns render accounts of rape culture less abstract, but that is not all they do. They also repeatedly signal slippage between subject and object, agency and objectification, offering a resonant chronicle of the effects of trauma. Bhanu Kapil observes that “[i]n a shamanic or trauma theory model, the body streams towards the place where a scrap of it is held. In the butcher’s shop. On a hook. And so on. A recursion.” Melnick’s poems bear this out, streaming toward landscapes of originary violence and spotting within them both the self and the self as object: “If I’m not a trinket I blend into concrete” (5). Trivial ornament and invisibility are the only known options in this scene, the speaker soon identifying herself with debased content: “I was smut” (8). Lines like this invite the reader, as Calista McRae has observed, to ask where agency inheres. To express that “I let the riffraff envenom my body” (1) is to assign the subject agency only to acquiesce, and to situate the body as the recipient object of a poisonous transitive verb. How can a victim wriggle out from a sentence that pins her, grammatically and rhetorically, in the objective case?

Few poets have so aptly captured the victim’s predicament in the mechanisms of language itself. Landscape with Sex and Violence repeats a sentence pattern in which a linking verb joins an “I” to a predicate nominative: “I’m yours,” for example, is the bitterly ironic end of “Some Ideas for Existing in Public,” a poem about street harassment (the poem for our time about street harassment), and elsewhere, the speaker states, “I’m no one.” The pattern recurs throughout the book, replacing the subject “I” with “more and more of what I am: kaput // hot-to-trot” (75). The “I” lands on its definition in the modifiers of rape culture (“hot-to-trot”), and in the crosshairs of its constraints:

I am only ever trapped inside

my own fixed vantage point or else I am

convention (48)

I’m no lady anywhere

and, like the sequoia that died

girdled on display,

I’m older than I look. (49)

This self is predicated on confinement, then on “convention,” then on the terms “lady” and “older,” loaded signifiers for women. No wonder the speaker attempts to manipulate the erotic and destructive energies that ensnare her: “I tried to detonate my body / differently than he did” (26).

Melnick’s work, like that of all our best poets, embraces both poles of poetic articulation Nathaniel Mackey calls “check and enchantment”[3]: on one hand, it issues critique, checks injustice, and exposes the workings of power and dominance; on the other, it summons the force of incantation, of song. Another one of Mackey’s dichotomies is the poetic tension between “nomination and agnosis” — naming and doubt, the knowing of the thing and its uncertain epistemology. Name it, say it. But how can we name it, or say it? Nomination as a poetic principle in Melnick’s work — strenuous interrogation of language’s nominal capacities — draws the reader into an intricate and vulnerable web where subjectivity finds itself enmeshed in person, place, and thing:

I fold over to smell myself.

Route 66 to Las Vegas.

Perfect for a child and also America

loves the promise of a long haul.

I pull the tab from a small can of apple juice:

see?

I’m cared for. (13)

The speaker struggles for self-recognition in a landscape where a token of nourishment is mistaken for care. The poem retraces the road trip, as Kapil suggests the survivor of trauma must, going back for the pieces of the self that are left behind.

These pieces accrue to create narratives of shifting significance. One poem identifies an artifact of a childhood that is cut short by initiation into violence. The noun in focus is a “hook-rug,” a recreational craft, then the poem swerves abruptly to “dick” and “car,” then “asphalt,” “sweat,” and “rubber” (32–35). In another poem, nouns mark the body as both eroticized and wounded within the décor: “bruises,” “breaks,” “tits,” “string-lights” (57). In another, short “i” assonance enchains “clinic,” “fat lip,” and “kiss,” a series that leads to the polluted moral ecology signaled by “chemtrails” (54). Sonic effects relentlessly link the nouns that solidify rape culture’s rhetorics. “Smut” connects with “slut” and “strut,” and the poem becomes a symphony in the key of short “u,” the “uh” of hesitation and stuckness and confusion — “I fuck a man shilling for Jesus” (40). Interconnected by their sounds, concrete nouns throughout the book are a scatter graph against grids of abstract nouns that define the cognitive and emotional fields of the speakers’ experiences: “Your fervency. Your remorse.” Desire and regret, eros and fear, propel the poems’ speakers through urgent interpretations of artifacts and products, flora and fragments: “and real quick I understood enough about bigotry and drought” (72).

Nomination as a principle of composition, as Stein knew, carries the risk of becoming static, inert, but Melnick forestalls that possibility with whiplash enjambment. Enjambment in these poems functions as the counterforce to the nominal, and moreover, it generates within the poems an unfolding process of disambiguation. If the pairs of titular nouns function as guidewords that head the columns in a dictionary — then radical enjambment sets in motion the cuts and breaks that allow movement among multiple meanings. Disambiguation, a term often used with regard to search engines, refers to a process of resolving conflicts among multiple semantic or grammatical interpretations, and Melnick’s poems do just that. Enjambed lines activate polysemy to make a situation’s danger clear:

while I moan you can’t leave

handprints on my throat. (50)

As a term in computation, “word-sense disambiguation” refers to the mind’s capacity to determine the relevant usage among several possibilities. These poems take up the lexicon of rape culture (slut, smut, lush, bitch, asking for it, hot-to-trot), turn the words over on the page, expose them to light, and force confrontations with their meanings and inferences in overlapping contexts that include crime, law, medicine, anatomy, addiction and treatment, fashion, television, and consumer culture.

Melnick’s poems parse their own terms, pointing out how we tease out meanings under the influence of pressing external forces (worry about that word tease, then worry about it harder):

Across the alley way from myself there I am

lit by Hollywood in a decalescent dress (79)

In this moment of dissociated self-awareness where the self observes the self from a distance, the line break underscores the rift between self-actualization (“I am”) and the predicate nominative that clinches it. In this case the sentence lands on a term — “lit” — that vibrates in at least three directions, from illumination to intoxication to chic. Here’s another enjambment that severs an expectation, conditioned by rape culture, from the self’s actuality:

… grubs have fed on me in every season

because I’m a lush

tacky annual unwinding in rare humidity toward self-burial

or, I mean

once I pull my true self from the split. (80)

A reader (or a jury) might jump to the conclusion that this speaker is a drinker (the classic victim-blaming tactic), before realizing she imagines herself a flower, déclassé and decorative, and then wrests something that resembles regrowth, a “true self,” from the rupture.

This book does its critical work through lexical work, dictionary work: it is a wordsmith’s inquiry and a cultural historian’s glossary of terms. Most explicitly, “Landscape with Thesaurus and Awe” quantifies and queries the words we use to capture conflictual feelings of longing: “There are 24 synonyms for the word envy” (63). The stakes of this inquiry are high, and the means available for the investigation are neither safe nor easy: “I am furious for answers / inside the book of words I stole from a stranger’s back pocket” (63). Furtive, enraged, this seeker is working with a stolen lexicon, and with the inescapable awareness, as Adrienne Rich so aptly expressed it, that “this is the oppressor’s language but I need it to talk to you.”[4] She discovers

There are 5 synonyms for the word redemption

and 46 for fear.

One of them is chickenheartedness

and another is awe and

only my body is for sale. (64)

Melnick’s poems tread into taboo, asking how women’s experiences of sex work, abortion, and abuse are enmeshed in the available language for the interactions that constrain their fates.

In these poems, the work of definition, of codifying meaning and usage, is never merely academic, and defining a person vis-à-vis their sexuality is often a precondition for exploitation: “Some folks like to use the word slut, even with children” (7). A word’s usage, Melnick reminds us, shapes our perceptions of a person’s worth: “girls vibrate urgently for your tips and when I say girls // I mean that” (65). The words that caption a scene determine the fate of the person within the scene. Most memorably, the harrowing recollection of a rape requires “a more serious set of adjectives” (12) than initially thought:

I hire a skywriter to describe me:

voluptuous, terrified, bewitching, willing to wait

[…]

the skywriter got confused and wrote:

terrified, showstopping, mute, asking for it (11)

Fear is irreducible, a constant; the other terms shift from attraction to threat. Melnick’s speaker views and reviews the trauma through the shift of connotations, and this lexical work makes the articulation of the account possible. As in the detonating line in Patricia Lockwood’s “Rape Joke,” where she wonders if writing the poem is “asking for it to become the only thing people remember about you,” the phrase “asking for it” triggers an implosion of misplaced guilt and justifiable dread.

Melnick’s assemblages reveal the extent to which rape culture compromises the idea of home. The book begins with “Landscape with Stucco and Dandelion,” where the common residential building material in the southwest and the familiar wildflower of the unkempt lawn encapsulate formative circumstances. Later, when the poems’ titles depart from the pattern of two-noun anchors, the effects of trauma are writ large in more ambiguous spaces, as if refuge were barely imaginable: “Landscape with Somewhere Else Now,” “Landscape with Dissociation.” Melnick gives “local habitation and a name” not to airy nothing but to an ideology that unravels efforts to secure a habitat in the first place. As she puts it, point blank, in a poem published elsewhere on the occasion of Trump’s inauguration: “Do you know what it’s like when a body twice yours / holds you down in the room where you make your life?” The rooms depicted in this collection, whether framed by stucco and dandelion or improvised “in the desert in a Datsun” (85), are sites where physical reality gives way to lasting psychological effects: “(tarmac, blacktop, lonesome)” (78).

For Melnick, as for Stein, poetry is a rigorous practice of searching for nouns that come close or closer to being the right word for the thing: “I go hunting for another word for hypervigilance / and someone asks if I mean hopefulness. // I do not. / But whatever” (76). Nomination implies agnosis — misunderstanding, inadequacy, any surety of knowing undercut by the possibility of shunning or denying that knowledge. In these lines, from a poem near the end of Landscape with Sex and Violence, the speaker claims not to mean “hopefulness,” to doubt that her attention to detail, her “hypervigilance,” can take her there. Yet the book ends on a note of hope nonetheless: “but this, all of this, the rape and the allegory // and the skinny palms sheltering no one: // this is the story of how I got to live”:

I lived

in a desert

where palms are signposts of water, not the want of it. (86)

Hope and survival are perceptible, but they are not the same thing. Neither are habitation and sanctuary. Melnick’s first book, If I Should Say I Have Hope, contains the elusive noun “hope” in its title, but it is couched in the conditional and the prescriptive, and it takes six words and two separate “I”s to get there. Hope, in Melnick’s work, is something tangible, like a nutrient. A person can be deficient in it, but it can be supplemented, restored. Landscape with Sex and Violence is a tonic, a necessary intervention that delivers restorative vigor, uncovering openings for change at the level of signifier and horizon.

1. Gertrude Stein, “Poetry and Grammar,” in Lectures in America (Boston: Beacon Press, 1985), 327.

2. Lynn Melnick, Landscape with Sex and Violence (Portland: YesYes Books, 2017), 65.

3. Nathaniel Mackey, “Preface,” in Blue Fasa (New York: New Directions, 2015).

4. See Adrienne Rich, “The Burning of Paper Instead of Children.”