A catalogue of poetics as community

A review of two Slack Buddha Press chapbooks

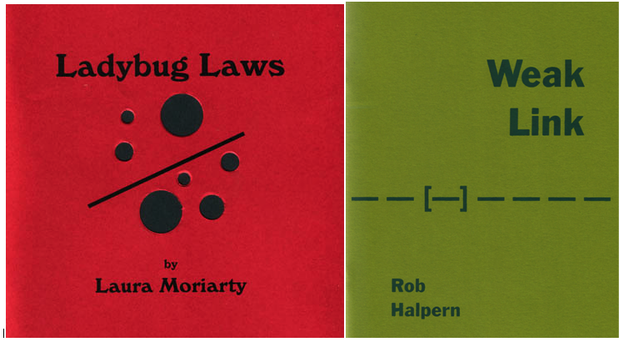

Ladybug Laws

Ladybug Laws

Weak Link

Weak Link

In the very place where the machine he must serve reigns supreme, [the worker] cunningly takes pleasure in finding a way to create gratuitous products whose sole purpose is to signify his own capabilities through his work and to confirm his solidarity with other workers or his family through spending his time in this way.

— Michael de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life

La Perruque Editions, the chapbook arm of Cincinnati publisher Slack Buddha, takes its name from philosopher and social critic Michael de Certeau. In his book The Practice of Everyday Life, de Certeau introduces the term “la perruque” to describe the act of individuals using company workspace, time, and materials to pursue their own creative endeavors — all while maintaining the appearance of working for their employer. It’s a humorously subversive name, one that speaks to the basic condition of many contemporary poets and visual artists (even as I type this now at my office, I’m glancing back over my shoulder to see if my boss is about to round the corner).

The concept of “la perruque” deals with a question that often seems to be at the forefront of discussions concerning what it takes for the contemporary creative act to exist, especially in a culture that increasingly devalues it: how to make the time to read, write, publish, or otherwise actively engage oneself with a poetic community when stuck in a cubicle eight or more hours every day? Exemplified by the Flarf Collective, who used their time in office spaces to create an internet-based, email-exchanged poetic practice, or projecting even further back to the image of William Carlos Williams, doctor’s pad in hand, crafting poems in between patients, the time, space, and conditions of contemporary work models have provided poets with new ways to reclaim the everyday vitality of the creative act — ways that also subvert the increasingly mechanized roles of individuals working in the office environment.

Since 2003, La Perruque Editions has released chapbooks by more than thirty poets as well as work by visual and performance artists including Mel Nichols, Ric Royer, Benjamin Friedlander, and Susan M. Schultz. The press’s aesthetic is, for the most part, simple: heavy cardstock, screen-printed or photocopied covers, often with overlays or cutouts, which highlight the idea of each of these works as something tactile, handmade, as coming from an individual or small group. This attention to detail, as well as the work itself, which tends to focus on the visual/concrete and the political, speaks to Slack Buddha’s efforts to craft a catalogue of poetics as community, as a return to conversation and physical exchange between people in an increasingly dissociated time.

In the chapbooks Ladybug Laws by Laura Moriarty and Weak Link by Rob Halpern, this act of reexamining and renewing the interpersonal becomes central to both thematic concerns and prosodic choices.

Slack Buddha Press is located in a nineteenth-century brewery-cum-ice cream factory in Cincinnati, Ohio.

Laura Moriarty, Ladybug Laws

Examining the life of patterns and color, Moriarty’s poems in Ladybug Laws suggest the various intersections of both backdrop and detail, or what can also be seen as the interplay between an autonomous unit and its larger environmental setting. These concerns persist throughout the chap: how the dot patterns play (or write) upon a red field of the shell; how both the small and the large react to and alter aspects of each other, much like the proverbial butterfly who, by flapping its wings, creates a monsoon thousands of miles away: “I produce enormous events” (“Smitten”). Ladybug Laws spells out a basic connectivity that is, at once, neither absolute nor categorical. Instead, Moriarty’s ladybugs move in spaces of indeterminacy, of fluidity: “Coating Thoreau / With herself preferably / A verb now […]. Swaps thy for thou / thee for me” (“Green Lady”). The space between the body of the poet and bug shrinks until it becomes virtually nonexistent, in a lighter, more conceptual take on David Cronenburg’s phantasmagoria: “Ladybug obvious / Hybrid of bug and lady / Unthinkable state […]” and “Not of but was / Jeff Goldblum / Sloughs off // his Human in / the Fly —” (“Flown”). Or the space between selves fills with the endless reproductions of life, as in her response to the Andrew Bird song “Imitosis”: “Read as the green / Of the creatures / Between us.” Imitating mitosis, on the level of relationship, invokes the sense of an aggregate body; Moriarty’s ontological examination is filtered through the perspective of a swarm, imagining how the individual positions herself in relation to another. Incorporating the language of other writers, such as Elizabeth Robinson in “Green Lady” or Alan Halsey in “Ladybug Honey” and “Ladybug’s Lament,” also evokes the sense of a swarm or colony: the language of others becomes part of the poet’s own movement throughout the poem as different source words work together to enact ever-changing structures.

A focus on blurring the borders of voice and body gives interrogative s hape to this collection. However, the sonic and referential porosity of words further defines this shape: “Read red as read / Lady as later // Song as wrong” (“Ladybug Song”). The words bleed into each other, drawing attention to the inherently elusive act of definition. The chapbook’s repeated theme of “read” versus “red,” its use of homophony to shift or morph meanings, emphasizes Moriarty’s inquiry into the act of recording: “We can barely see what’s out there / Overwhelmed as we are by repetition / Though I depend on it for what sense / Of continuity remains to me when / I see you I know I am at work” (“Ladybug Laws”). Moriarty’s consistent use of mondegreens and homonyms also illustrates both the cloudy repetitiveness of perception and the infinite, subtle variations that occur both in the creative act and in the natural world. The action of navigating currents of musical, social, and biological variations sustains these poems’ presences, their immediacies; it also makes for a beautifully lyrical, intellectually astute, and finely detailed reading experience.

hape to this collection. However, the sonic and referential porosity of words further defines this shape: “Read red as read / Lady as later // Song as wrong” (“Ladybug Song”). The words bleed into each other, drawing attention to the inherently elusive act of definition. The chapbook’s repeated theme of “read” versus “red,” its use of homophony to shift or morph meanings, emphasizes Moriarty’s inquiry into the act of recording: “We can barely see what’s out there / Overwhelmed as we are by repetition / Though I depend on it for what sense / Of continuity remains to me when / I see you I know I am at work” (“Ladybug Laws”). Moriarty’s consistent use of mondegreens and homonyms also illustrates both the cloudy repetitiveness of perception and the infinite, subtle variations that occur both in the creative act and in the natural world. The action of navigating currents of musical, social, and biological variations sustains these poems’ presences, their immediacies; it also makes for a beautifully lyrical, intellectually astute, and finely detailed reading experience.

Rob Halpern, Weak Link

It’s time that intellectual discourse of the left learn from the operatic emotionality of the right.

— Dodie Bellamy, “Body Language”

In a remarkable combination of emotional and theoretical speech, Rob Halpern’s chapbook Weak Link calls attention to a series of erosions, social spots that have lost their stability. In the wake of overwhelming U.S. military violence and political abuses within an increasingly apathetic and amnesiac culture, Halpern reconnects the experiences of the body to these larger, political movements, effectively drawing the reader back into their immediate physical existence. Through this embodied reconnecting, Halpern’s poetry enacts a social critique that doesn’t proselytize or dictate, but rather reminds the reader, like Charles Olson before him, that the root of politics, the “polis” (sharing a source term with the Ancient Greek for “pelvis”) is always centered in the physical.

Weak Link opens with a quote that is attributed to, as Halpern notes, a “Forgotten Source.” This draws immediate attention to and simultaneously obscures the authority of a outside source voice, one that could otherwise provide an accurate point of introduction to the concerns of these poems. Decentered from the very beginning, Halpern’s book next provides a stylized “Legend” for the work, which functions as a sort of list poem and apophatic description of the collection’s prevalent use of em dashes surrounded by brackets. This prefatory piece moves through statements of what a weak link does not equal, and in doing so allows the occurrence of each weak link in the chap (visually represented by the bracketed em dash throughout the poems) to function as a space of, often, indefinable loss.

[—] pumping my disturbance with phonation

Days go by, open vowels, not generating much future

Sound [—] losses where all this will have happened

Any common place [—] strung out on being still

Produced disfigured gently now my ratcheted dejecta

[—] his leg becomes my fluted stump, my lip

His anal spur [—] missing tongues insert the word

Whose shock force grids resistant salvage, ours

Being squandered in advance, we molt in network

Fibers, having traced the place of future action

What can't be named in a field of roots, so come

Inside my fjord of mannered stools [—] watch

—the eyes peel back, so pasted to the blazing. (13)

This focus on the ineffable and its correlation to the embodied, as well as the collection’s varied use of caesura and enjambment for corollary meanings across lines, creates a natural affinity between this chap and Halpern’s excellent book-length Disaster Suites (Palm Press, 2009), a lyrical engagement struggling to speak in spaces of disaster and dis-ease.

In Weak Link, the dialectic between the lyrical and the disastrous event occurs as a blurring or merging of the two, often describing a tandem loss of physical and emotional space: “Here we feel the pressing [—] the loss of woodland / Scenery under national, yr transmission // Just bellies up and dies” (8). The body moves from the arboreal to the mechanical, and loss— the breaking down of self-contained systems, in conceptions of both nature and industry— occurs concurrently. The mechanical mirrors the loss of the natural, as the transmission (word/message or gear system) reveals itself to be alive, organic, ultimately dying “belly-up.” Here Halpern fills in the space between often opposing concepts to get at the root of weakness, of the inherent vulnerability at the foundation of all systems, as well as the necessary loss of illusionary control this entails.

The intersection of the abstracted/mechanical and the immediate/physical also frame moments of intense intimacy between individuals in these pieces: “I have / Sown dark clouds above our bed the beautiful // Sounds of circuits memory and capital my treat- / Ment of the subject won’t save us from the total / Oblivion in becoming objective social fact” (20). In lines that introduce another core dialectic at play—the body/mind dynamic—especially as it speaks to historical record in the act of writing, Halpern makes a strikingly pointed statement about the opaque, endlessly complex relationships between the physical body and the body politic: “In public we reckon impossible tense, shame // On our white floors, becoming impossible / Bodies extracted by the thousands” (7). What is so effectively brought into focus here is the extreme reality of lost life: a body displaced or victimized by war and foreign occupation is consistently abstracted into conceptual forms such as “alien,” “enemy,” or “collateral.” This is a process of “othering” that Halpern draws close attention to, a system used to reduce or negate individuals’ basic humanity, which, in turn, serves to “weaken the links” in social consciousness, allowing for untold abuses by a hypermilitarized state. Ultimately, in this system it is never just the “other” but also the self, the connected “our,” that is labeled suspect: “Skins glow, organs crave yr foresworn illegal / Touch, they’ve traced powder in our stools // Therein lies the nation’s intelligence, a gap in stills” (24). In this charged journeying between philosophical concerns and the immediate processes of the sensate body, a closeness that reaches past obscure rhetorical gesture is delineated. The poems in Weak Link call for a movement of the heart, engaging readers to perceptually restrengthen the links within themselves.

More from Rob Halpern in Jacket 40

More from Laura Moriarty in Jacket 40