The beast that therefore I am

Eight recent poetry titles on the beast

Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths

Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths

Beast Feast

Beast Feast

Bestiary

Bestiary

You, Beast

You, Beast

Like a Beast

Like a Beast

Beast

Beast

Ordinary Beast

Ordinary Beast

Beast Meridian

Beast Meridian

I have been a made thing & a hunted thing — Cody-Rose Clevidence[1]

Eight poetry collections published in the past four years turn to the beast as an alternative way of inhabiting the world. This beastly turn has ontological, political, and aesthetic implications for how we theorize the relationship between poetry and personhood (and all of its Enlightenment-era baggage). This review explores both the impetuses and outcomes of these beast-filled encounters but stops short of offering a grand theory of “the beast,” as such a move would undermine the motivating reasons for embodying and embracing beasts as kin.

Before turning to these collections, I want to contextualize the beast in the human/animal relationship that Jacques Derrida deconstructs in his critical work The Animal That Therefore I Am. In it, Derrida subverts René Descartes’s rational, humanist cogito ergo sum (I think therefore I am), a logic that constructs a rigid boundary between humans and animals based on the capacity for thought. Derrida problematizes this dichotomy and undermines Western philosophy’s definition of “the human” as not an animal. Derrida’s view of the intertwined relationship of humans and animals is illustrated by the book’s title in the original French: L’animal que donc je suis. Here, je suis means both “I am” and “I am following,” tying identity to genealogy, proximity, and even violence (the hunter who follows the animal).

The brand of humanism deconstructed by Derrida also reifies taxonomical distinction into ontological essentialism as, historically, the discourse of species and race have been conflated to justify colonial violence and dehumanization. Critic Cary Wolfe names this apparatus of power the “institution of speciesism” in which the “noncriminal putting to death” of animals is ethically accepted and extended “to mark any social other.”[2] The beast, however, is by definition that which is always already marked for socially acceptable extermination. It not only excuses violence, it incites it. Living within the sacrifice zone, the beast becomes other even to “the animal.” So: how does turning to the beast or a beast or beastliness redefine these central questions of identity, otherness, and history inherent in the struggle to define humanness?

The beasts across these collections do not offer a unified answer to this question. However, some productive themes and concerns can be identified when these eight collections are brought into close proximity, themselves creating an intriguing poetic bestiary for our contemporary moment. From the forgotten origin stories of “sacred monsters” in Acevedo’s Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths, to the taxonomy of family ailments in Sealey’s Ordinary Beast, these beast-filled books nuance and challenge the categories of self, other, and history.

Beast that I am

In her article “Lesbian Spectacles,” theorist Barbara Johnson considers the limits of “speaking as a” — meaning, to address the world from the perspective of a specific, stabilized identity.[3] The problem with trying to speak as a lesbian, she writes, is that she might be inadvertently representing the image of what a lesbian should be, the identity that was packaged and sold to her through the media and through her own partial experiences. This problem is still pressing, and one that writers aware of the publishing industry’s desire for marketable identities are constantly fighting. Anthony Reed in Freedom Time poses a similar question regarding race and identity: “How does one change the valences of the burdens of black writing in a society where people presume to know in advance what one will say?”[4] Johnson and Reed frame two of the central concerns expressed in these poetry collections — the problem of writing as a and the expectations of publishers and readers for what a poet’s expression should look or sound like based on that poet’s discernable identity. The beast, however, offers a point on the intersectional grid of identity that both holds and reconfigures multiple expressions and ways of being.

Beast Feast by Cody-Rose Clevidence confronts these issues by first addressing the base unit of identity construction: language itself. Standardized grammar and syntax demand a certain relationship between subject and object, singular and plural — they/we/he/she/I. The proem of this collection, “Be Prepared for Many Forms,” announces as its object the deconstruction of language and concepts that stifle certain forms of expression:

*[words in use in the world are in conversation & are erecting certain structures of thought in relation to the world & to other uses of these words & this is an argument re: “natural” “animal” “world” etc.][5]

Clevidence’s language and forms accumulate, accrete, and mutate, producing a fecundity of meaning and possibility. The poem “[ZYG]” formally enacts this deconstruction of identity and language:

Queerne

ssnecessi

tiesarad

icalizedl

anguage

basedint

hedissol

utionofth

eboundar

iesthatus

uallycirc

learound

concepts[6]

In doing so, expression becomes inseparable from its method, disallowing the separation of form and content that can then be parceled out into discrete identity categories. This form also reveals the reader’s desire to reconfigure the poem’s given syntax in order for its meaning to match the conventional structures of grammar that organize thought. The tension between accepting these new thought formations and reconfiguring them to align with preestablished norms enacts the very positionality of the beast — that which is necessary as an Other against which order is established and that which threatens the very existence of that order.

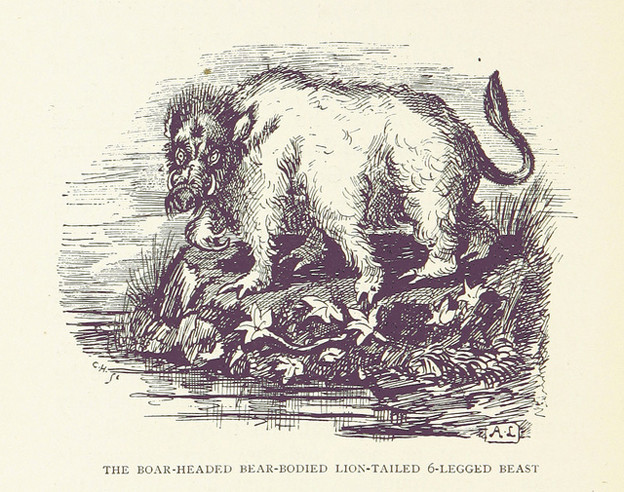

Donika Kelly’s Bestiary and Frances Justine Post’s Beast also rewire circuits of identity but do so through the method of self-portraiture. A bestiary, or compendium of beasts, is a medieval genre that categorizes the real along with the mystical, the imaginary with the ordinary. Kelly’s Bestiary is taxonomical in its logic, though this effort to chart the self continually results in a blurring of distinctions rather than a reification of categories. Throughout the collection, Kelly’s “Self Portrait as ___” poems draw us back into Johnson’s territory of “speaking as a ____.” Johnson’s solution to the problem of “treating as known the very predicate I was trying to discover” is “catching myself in the act of reading like a lesbian,” rather than directly setting out with that task in mind.[7] There is a similar tactic of evasion — of catching oneself in the act of reflection, of tracing the moment when the self turns from subject to object in order to inspect itself — throughout Kelly’s self-portrait poems. She transforms herself into various objects and others in order to catch a glimpse of that self being re-presented: “Self-Portrait as a Block of Ice,” “Self-Portrait as a Door,” “Self-Portrait as a Wooden Flower.” These poems serve as counterpoints to the series of love poems for creatures in the bestiary — specifically those that shift shapes or live between taxonomies: “Love Poem: Chimera,” “Love Poem: Pegasus,” “Love Poem: Centaur,” “Love Poem: Satyr,” “Love Poem: Werewolf.” These hybrid addresses and partial representations of the self together offer a method of charting the many forms of one’s identity without pinning them down into any single ontological category.

The proem in Post’s Beast, “Self-Portrait as Beast,” establishes the reflexive act of self-representation as one that multiplies rather than stabilizes. To represent the self is to represent transformation, the movement from one becoming to the next: “I put on my face. This one is wolfish, / covered in whorls of black and gray fur.”[8] This self-portrait cannot name what is, as there is no stable self to portray. This is not a scene in which a human dons the mask of an Other that it can then remove, but in which the whole face, the site of ethical comportment, is transformed over and over again. This act offers a distinction between ethical and exploitative empathy, a critical conversation in poetry today surrounding the question of persona, power, and appropriation. The self in question here does not step in and out of these other selves, a temporary and exploitative form of empathy, but becomes a site of encounter itself, an accretion of identities that widen, harden, and diverge.

In Post’s other self-portrait poems, the self is revealed to always already be selves, though again the grammar that structures identity constrains this mode of being: “We’ll quiet / then we’ll not. We’ll speak in the singular.”[9] The concept of the singular self continues to splinter as it is constructed in terms of movement and multitude: “Self-Portrait as Maelstrom,” “Self-Portrait as Pack of Wolves,” “Self-Portrait as the Crumbs You Dropped.” The work of the self-portrait here is to construct but not reify, to offer a face but not the face. These portraits do not cohere a self that has been fragmented by modernization, nor do they attempt to distance the self-as-speaker from the poet; rather they affirm the presence of many selves that need not be reconciled into any coherent whole but that can be accounted for nonetheless. These poets have perhaps found another answer to Johnson’s concern about “speaking as a” by speaking as many.

Beast that you are

You, Beast by Nick Lantz directly addresses beastly others. And as we know when we see the second person used in a poem, this address is nearly always also directed at the one who is speaking. The structure of this address is a necessary framework for reinterpreting who gets to respond and whose response is considered meaningful in this act of interpellation. Lantz’s fabular opening poem “Posthumanism” models what it looks like when we think about signification beyond our human-centered linguistic system. “In the good old days,” the poem begins, “the lords / summering in the country / paid peasants to beat / the ponds … so the frogs would stay / silent.”[10] Imbricated in a feudal system of exploitation is the transformation of animals into silent objects. But then “one evening,” the poem continues, time stops and a new set of relations becomes possible:

A driver

rolled down his window.

“Hey!” he shouted. “Hey!”

said a blue jay on a mailbox.

“Hey!” said a squirrel to a dog.

“Hey!” said the driver.

“Hey!” said the dog.

“Hey!” said the driver.

“Hey!” said the bees.

“Hey!” said the flower. “Hey!”[11]

Posthumanism, it seems, might be the answer to humanism’s essentializing tendencies. Though N. Katherine Hayles, Donna Haraway, Cary Wolfe, and others all have different interpretations of posthumanism, simply put, we might think of it as a mode of thought that resists anthropocentrism by countering the systems of rationality and autonomy that justify this human exceptionalism. At its best, posthumanism allows us to understand how humans are not independent wholes but creatures that are constituted in and through our relations with the more-than-human world. At its worst, posthumanism eschews the body for the fantasy of freedom via technology and reinforces the very category of “human” it is purportedly trying to deconstruct. Zakiyyah Iman Jackson explains how many posthumanists, despite their attempts to deconstruct binaries such as human/animal, are still entrenched in Western values of rationality: “While post-humanism may have dealt a powerful blow to the Enlightenment subject’s claims of sovereignty, autonomy, and exceptionalism with respect to nonhuman animals, technology, objects, and environment, the field has yet to sufficiently distance itself from Enlightenment’s hierarchies of rationality: ‘Reason’ was still, in effect, equated with Western and specifically Eurocentric structures of rationality.”[12] How, then, does this framework of “posthumanism” intersect with the beastly address of Lantz’s collection?

The key to not reproducing the aforementioned pitfalls of posthumanism might exist in this very structure of address. This poem in particular tropes on the lyric tradition of apostrophe, which Jonathan Culler describes as itself a “troping on the circuit of communication.”[13] Typically, the apostrophe is an address to one who is not expected, or able, to respond: someone or something dead, absent, or inanimate. However, nested within the collection’s apostrophe — (hey) you, beast — is the fabular remediation of address that shows how the ones we don’t expect to respond do. The reason for the beast’s historical lack of response is not the beast’s inability to respond, but that no one thought to address the beast, or if they did, they did not wait around to listen for an answer. The move from talking about to talking to might be the same transformation needed to maintain posthumanism as a mode of encounter rather than a mode of thinking that simply extends the typified structures of “Reason” outward without ever troubling those structures. When one addresses a beast and expects a response, even responds to that response, this address enlivens a new ecology of encounter, a new way of being in the world.

After this mode of address and response has been established, the collection continues by examining how humans tend to interact with particular others: a roach on a kitchen floor, a dove “vaporized” by a fastball, a grackle at Walmart. Lantz examines how anxieties about humanness are routed through animals, who serve as symbols to make meaning, fables to make morals, and companions to make humans feel less alone even as they both challenge and reinforce a hierarchy of human to nonhuman. Addressing the beast of one’s self in order to engage in the response from these beastly others complicates human and animal ways of knowing and being, turning posthuman into postanimal.

Carly Joy Miller’s Like A Beast measures the strangeness of the beast-as-other through simile. How much like a beast are we? What is the nature of being a beast? Through ontological inquiry and formal contiguity, these poems try to track their own scent, turning in circles with the recursive logic undergirding Derrida’s je suis (I am [following]). In “Dayshift as Conduit,” the speaker reports: “My mother told me I live / like a beast and like a beast // I will die.”[14] The simile at the center here chases its own tail, unable to draw any positive conclusions from this recursive loop of likeness. The crux of otherness, it seems, is located within the self, which can’t be seen by the “I” unless that self becomes an object able to be beheld. And yet at that moment of turning, the true glimpse into the self is lost, bound to wander the corridors of being like something but never actually being something. The question of how much like beasts we are is one continually repressed by a Cartesian logic that rests on the specialness of “the human.” This collection not only manifests that question but reverses it to ask: how much like humans are we?

Beast that has been

Beasts breed origin stories. They live through myth, amenable to revision and repetition but also resistant. In Elizabeth Acevedo’s Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths, beast merges with monster in the dynamic project of myth as a record of history that has been rejected as “real.” Just as John Berger writes that we lose access to some part of our humanity due to the loss of the animal gaze (a trait and product of modernity), we lose access to our unhumanity, our beastly origins, when we write them out of history.[15] In “La Ciguapa” Acevedo writes: “They say. They say. They say. Tuh, I’m lying. No one says. Who tells / her story anymore? … We who have forgotten all our sacred monsters.”[16] Monsters, like beasts, incite violence. They serve as the antagonists in stories in which humans prove their right to rule the nonhuman realm. For Acevedo, however, myth is the mechanism for remembering the kinship of beast and human, monster and mother. To forget that history is to lose a part of one’s culture and one’s self.

In Beast Meridian, Vanessa Angélica Villarreal redraws the contours of an imperialist history through the figures and stories generated by an ancestral bestiary. Beasts here become a method of countering the dehumanizing tactics of settler colonialism, which are reinscribed daily on the bodies of those who must confront the “widening line that splits your body in halves … that which separates you from home / you from history.”[17] Even if one were to reunite these halves, the result would not be a wholeness that has healed its trauma, but a body marked by it. A body one might call a beast. Villarreal charts the movements of a “halo of beasts” who are loved “with the knowledge of our ways lost to violence.”[18] In “Horned Woman Ancestor,” kinship is known by such a mark: “I will know you by your heavy horns and two faces / to look always South as you look North // to survive this nightmare so American.”[19] The split caused by the border, the meridian that pierces this book, not only configures social relations and economic security, but time and space. The Janus of Greek myth is remade, as the ancestor gazes across a land marked by violence in which the future is not something that can be looked forward to but must instead be survived into. The beast, then, is not a singular figure but a constellation born from the lines written over and over again to “repair the seams between worlds along its meridians.”[20] The beast is a set of relations, a kinship that cannot be reified but known only by the movement across and between bodies and places.

Finally, Nicole Sealey’s Ordinary Beast returns us to the doubleness of the je suis — the being and following that inheres in her journey to follow her own self as she explores taxonomies and genealogies of kin and language. The opening poem, “medical history,” presents the reader with a list of facts about the speaker and those close to her: “I’ve been pregnant. I’ve had sex with a man / who’s had sex with men. I can’t sleep.”[21] A list of objective facts soon transforms into more subjective experiences, as the line between what should be included or excluded on this imagined intake form quickly dissolves. It becomes impossible to know what is relevant information — who is to say that her knowledge of dead stars is not as pertinent to her medical condition as her sexual history? The attempt to chart symptoms and relations and the inevitable subversion of a linear concept of history is a defining tension of this book. Personal history is never discrete, but a pattern intersecting with the lives and actions of so many others. To know the self becomes an impossible feat, at least if one understands that knowledge to be a stabilizing force.

What, then, is an ordinary beast, a phrase that seems to contradict itself, insofar as a beast is a figure of what is strange, other, and outside the realm of the ordinary? In Sealey’s work, ordinariness is ideology. It is the institutionalized way of being that was constructed to serve a few and exclude many. The beast interrupts this fantasy of the ordinary, of accepted and expected behavior. For example, the poem “hysterical strength” shows how the daily, ordinary experience of being black is, in fact, extraordinary: “the hysterical strength we must / possess to survive our very existence, / which I fear many believe is, and / treat as, itself a freak occurrence.”[22] Violence and racism are ordinary insofar as they are structural. To continue existing is not a matter of fact but a constant confrontation with a system that actively works against one’s survival. To survive the ordinary, one must become like a beast, imbued with a more-than-ordinary strength like “a camper fighting off a grizzly / with her bare hands.”[23] And yet one cannot live in this constant state of emergency. The double bind of the beast is that it is excluded from the ordinary even though it is required as the opposing force that gives the ordinary its shape. Ordinary beast, then, is less a description of a type of beast and more a description of the tension between historically constructed relations that mirror and intersect with the human/animal dichotomy that Derrida deconstructs.

What draws these collections together, beyond their engagement with beasts and beastliness, is their self-conscious engagement with the ecology of identity and its fractious relationship with history, language, and humanism. The lessons of deconstruction have been thoroughly absorbed and are ripe for interrogation as these poets probe the limits of a theory of identity based on negativity or différance. The result of this encounter is a poetics and politics of affirmation that does not revert to essentialism. In other words, identity is neither revealed nor eschewed in these collections, but configured through a beastly coalition of material, political, and aesthetic practices that resist the narrow grammar of selfhood asserted by humanism and even deconstruction. The political urgencies of our contemporary moment cannot be answered with humanist tactics of “inclusion,” which simply mask the fact that the unmarked subject at the center has yet to be toppled. Nor can they be answered with endless play of deferral in which language becomes separated from materiality and lived experience. Rather, these urgencies demand multiplying presences, accretions, and excesses that do not depend upon any predetermined taxonomy for acceptance yet still endeavor to demonstrate the encounters that shape and reshape one’s way of being, one’s possibility of being, in the world. They require, in short, a beastly ontology.

1. Cody-Rose Clevidence, Beast Feast (Boise, ID: Ahsahta Press, 2014), 79.

2. Cary Wolfe, Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 7.

3. Barbara Johnson, The Barbara Johnson Reader: The Surprise of Otherness, ed. Melissa Feuerstein et al. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press Books, 2014), 141.

4. Anthony Reed, Freedom Time: The Poetics and Politics of Black Experimental Writing (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2014), 20.

8. Frances Justine Post, Beast (Berkeley, CA: Augury Books, 2014), 15.

10. Nick Lantz, You, Beast (Madison, WI: Wisconsin University Press, 2017), 3.

12. Zakkiyah Iman Jackson, “Animal: New Directions in the Theorization of Race and Posthumanism,” Feminist Studies 39, no. 3 (2013): 672.

13. Jonathan Culler, “Lyric, History, and Genre,” New Literary History 40, no. 4 (2009): 887.

14. Carly Joy Miller, Like A Beast (Tallahassee, FL: Anhinga Press, 2017), 18.

15. John Berger, “Why Look at Animals?” in About Looking (New York: Pantheon Books, 1980), 1–26.

16. Elizabeth Acevedo, Beastgirl & Other Origin Myths (Portland, OR: YesYes Books, 2016), 2.

17. Vanessa Angélica Villarreal, Beast Meridian (Blacksburg, VA: Noemi Press, 2017), 78.

21. Nicole Sealey, Ordinary Beast (New York: Ecco Books, 2017)