Art-trash

On Chelsey Minnis and CAConrad

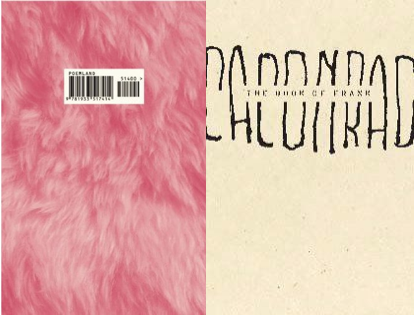

Poemland

Poemland

The Book of Frank

The Book of Frank

CAConrad is the son of white trash asphyxiation whose childhood included selling cut flowers along the highway for his mother and helping her shoplift. — author’s bio

This is a cut-down chandelier …

And it is like coughing at the piano before you start playing a terrible waltz …

The past should go away but it never does …

And it is like a swimming pool at the bottom of the stairs … — Chelsea Minnis, Poemland

What a trash

To annihilate each decade. — Sylvia Plath, “Lady Lazarus”

The argument

As these epigraphs so clearly emblematize, Art is asphyxiation; annihilation; anachronism; inebriation; something “cut-down”; something shoplifted; like trash, it makes more of itself; like the past, it should go away but it never does. Like a cough, it doubles up or doubles down on terribleness. It preempts itself by making multiple knockoff versions of itself; it is never sufficient because it is always more than enough. Through perverse excess, Art trashes conventional value, reassigning it to odd and ill-made receptacles which inevitably can’t hold; the chandelier is cut-down; asphyxiation has a baby; Art leaks and spills Art.

Drunk on Art (which is to say, poisoned —) the Artist can’t hold its liquor (which is to say, Art). Not all the vats upon the Rhine / Yield such an alcohol! — ED. Art spends its money on the wrong things. Art spends it all. Art eats breakfast at Tiffany’s: eats the book: like starvelings, the star and starlet suck words rather than speak them with queer pretty prostitute mouths: which is to say, unconvincingly; the ching-chong landlord has buck teeth taped to his teeth. Art speaks in teeth and not words. Art eats conflict, does a violence to violence, wears conflict diamonds in its teetering wig. The starlet eats tulips from beneath the Nazi boots. Moon River. Queer, syrupy tune. Art goes hungry on reverse clock time, Art’s record played backwards. The forehead of the exploited child splits, leaking Art. Moon River. Art is snaky like a trickle of blood down a child’s forehead or a Moon River: inside out peristalsis: it makes something present that makes something else disappear; that is, value; that is, time; something that should go away but doesn’t; sticks around, deformed and denatured and contaminating; dark matter. Artists are the life forms that live in Art’s gut; Art sheds Artists contaminated with Art; Artists are host-beasts that carry Art’s germs through the biosphere, their front legs trotting, their back legs galloping. Shitting Art like dew or conflict diamonds.

Inebriate of air am I, / And debauchee of dew, / Reeling, through endless summer days, / From inns of molten blue.

Dickinson-Artist, this little tippler, drinks, as they say, to excess. She is never full, because there is a hole in her. But she is saturated, then supersaturate, she reels, she tilts. Time is denatured, that is, made hypernatural for her, summer supersaturated with itself, shits an endless titrate, inns of molten blue which she also drinks and leaks. (In Poemland, “I’m so drunk I’m seeing toy bats …” (50))

A cut-down chandelier

What kind of mother is Art? What kind of child can it make for itself from trash, from shatters? Minnis’s poems form no body, not even a girl body.

If you want to be a poem-writer then I don’t know why …

It hurts like a puff sleeve dress on a child prostitute (15)

In the first line, the “then” refuses to mate with the “If” to make a conventional conditional statement. “Then” doesn’t follow from the previous clause so much as reject it, blanks out into not knowing: “I don’t know why” which then (paradoxically) double-blanks itself out with an ellipses. Like anorexia, it’s as if this thought cannot blank itself out enough and so inevitably underscores itself instead. Or like a cutter, scores itself, that is, scripts itself. So Minnis’s long poem exists in pieces, shreds and banners or snips that seem to poke up out of the skin of the page and want to subside into mystery but somehow only emphasize their long tails (the past should go away but it never does …). Every phrase is obsolete by the completion of its utterance, yet can’t leave the system. Unable to evacuate, it becomes a poison to the text (should go away but it never does …). Therefore it forms a modality that tends always toward Death. That’s how this four line sequence ends:

Nothing makes it very true …

Except the promised sincerity of death! (15)

Here the withdrawing ellipsis and the flourishing exclamation point have opposite but in both cases self-defeating (that is, self-killing) effects. The ellipsis wants to erase itself but overstates itself; the exclamation mark wants to voice sincerity but is so posed as to voice artifice. Both punctuation marks miss the mark. They overshoot the mark. They are divorced or sprained or autistic to the syntax of the lines, which is nearly autistic to itself, which is to say, inward directed, yet present in the world, unable to remove its symptoms from the world’s stage. A child prostitute’s puff sleeves which hurt, but hurt what? (“It hurts”), making a parody of presence to mark absence, the location of absence both gestured at and covered up with the exaggeration of something else. There is no selfsame body beneath those puff sleeves, no arms to hurt. Only an “It” and a “likeness”, exploited by Art for its ability to be like something else. Or we could take this line to mean that writing poems is like wearing the painful dress of the child prostitute; out of date, wrong sized for what you are pretending to be; exploited by some Other; that Other is Art.

It’s worth noting here that the “I” arises in Minnis’s poem in order to mark the site of non-agency; like her exclamation point which marks where sincerity is not, “I” marks the site where agency, thought, organized, individual consciousness is not. This emblematizes Art’s perverse way with valuation and devaluation. A line reads, “If you are not weak then I will start to feel like I have had enough of you …” (2). In this line, a quality (strength) is described by its double negative (not-weak). Minnis exploits her habitual conjectural “If/then,” a weak causality which can barely do its job; the “then” clause doesn’t attend to or follow on the “if” clause so much as reject it, drain away from it. Meanwhile the second clause, “I will start to feel like I have had enough of you” itself has a seesaw motion of rising and falling, draining and accruing, a future starting out, “I will start to feel,” a past piling up, “enough of you,” and past and future mysteriously linked around the fulcrum of “like,” an inverse (perverse) likeness. “Enough” is indexed to so many drainings and accumulations and conditionals and negatives that it hardly feels like an absolute value or location. Especially as it too is now discarded as the sequence continues:

But if you are weak …

Then this is a poem because it squeezes you …

It is a shimmer like flushing sequins down the toilet … (2)

Here the first ellipses suggests not silence as the absences of sound so much as a fullness of wordless gesture than takes up the whole next line: an inarticulable masturbatory fantasy on the white tiled bathroom floor. The poem returns to reward “you” with a “Then” which “squeezes you.” “It is a shimmer,” Art must exploit the world in order to articulate itself as a likeness, this time a likeness to “flushing sequins down the toilet.” Sequins instead of money; not something valuable, but something chintzy, decorative; trashing trash; Art’s redundant gesture; saturating the line with itself. Now the little ellipses turn optical, like sequins or a sequence making a spectacle of its trashing itself, flushing itself down the white porcelain toilet of the page, the readerly eye as a receptacle for the image, the hole in the toilet as the receptacle for the sequins, the hole of the page as a receptacle for the words, the world as the receptacle into which Art shits itself. Art says to its receptacle, “This is a chain for you, babe … / Babe, it goes around your throat …” (8)

*

This is like someone who pawns your minks …

And it is like a squandered money-gift …

This is the magic syphilis! …

There is no need for the truth …

Like scythes that cut through prom gowns … (80)

In Minnis’s Poemland, value is always something which empties itself out; the mink is pawned, the money-gift is squandered. Yet that trashing, that expenditure which makes a trinket of everything also makes an ornament of everything. “The magic syphilis! …” Art is over-marked, the amorous disease which trashes the body, reworks the decisive gesture as jerk and tremor (exclamation point AND ellipses), decorates the brain with lesion, converts the world to Art. It comes from traffic with prostitutes, and, “Like scythes that cut through prom gowns,” it wants to make another version of itself, a knockoff, a trashy horror-movie version of its would-be grand themes. “Oh, I walk in the red wool corset dress and carry the machete …” (98); “Poetry is my fondest stunt … like standing on my hands in a dress …” (98). Personal experience, even traumatic personal experience, prized materium of the first-person lyric, is here yet one more emblem or trinket of comparison for Art to wear on its chest: “To enchant someone meaninglessly … /Is like getting insulted and kissed by your writing instructor…” (24). The disturbance of each line break with ellipses or flagrant exclamation points; the excessive blank space between lines as if the lines have been denatured and cannot hold together in the natural body of a continuous thought; the way thought cannot run the circuit of the line breaks but rather keeps interrupting itself and tickishly picking itself back up (“This is like”; “And it is like”), marking itself as likeness and metaphor and never the thing itself — all denatures and dysfunctions both speech and thought, the supposedly distinctively human activities which the lyric is conventionally taken to mime. Minnis’s work suspends the suspension of disbelief in the lyric itself, and thus in speech, and thought, and thus in humanness and the prestige of being human:

Everyday I behave as though I am a human being …

And it hurts me to do it …

It is egotistically exhausting!

This is required to look like a poem … and to read like a poem …

But it’s really just some incomprehensible money … (63).

As she elsewhere concludes, “This kills the prestige! …” (106). When value systems are demolished, when the signature activity of value is to drain, scab, leak elsewhere, and leave behind little track marks of statement, exclamation, ellipsis, the entire denatured landscape cannot amount. Beauty does lie around here, though, like an arm, dislocated, or in pieces, divested of prestige, “like a cut-down chandelier.” Or elsewhere, the line is extra-saturated with beauty which can’t leave the system, which “should go away but it never does,” it supplies a toxic swimming pool of itself at the bottom of the stairs. “It’s like trying to drink a bottle of champagne in a roadside bathroom … / While holding on to a handle attached to a wall …” (38).

CAConrad is the son of white trash asphyxiation whose childhood included selling cut flowers along the highway for his mother and helping her shoplift.

What kind of mother is Art? What kind of child can it make for itself from trash, from shatters? CAConrad provides us an allegory for this in the form of his author’s bio. This Artist-son is born from Death, into Death, a very lowdown and ignoble Death (“white trash asphyxiation”), one that isn’t heterosexual (doesn’t involve two parents), doesn’t have a human body, a presence that’s in fact an absence (the absence of oxygen). Born into Death and Absence, the “son” enjoys an inverted version of life, a life with no center, on the margins, “along the highway,” selling trashed cut flowers and shoplifting, activities which continue the logic of exploitation and non-sustenance, but also of an improvised existence.

In The Book of Frank, CAConrad recasts this birth; he makes a cast of this birth; he casts a new son from it; like Warhol, he generates counterfeits and multiples; like Warhol, these images start to resemble one another, to enjoy a paradoxical life in and as Art that totally replaces the horizon line of conventional biology, temporality and experience. Like Poemland, The Book of Frank “trashes” value, but unlike Poemland here a countervalue is allowed to accrue, albeit erratically, from poem to poem in the figure of this continuous, if paradoxical, character. Where Poemland denatures the convention of “continuity” among successive lines on a page, The Book of Frank makes unconventional use of the two-page spread, especially in its first section. On one such spread, on the left side of the page Frank’s mother prefers her miscarriages, jarred in formaldehyde, to her “live” boy. She remarks, “you are too big for a jar my child / you will betray me the rest of your life” (4). On the right side of the page, an alternate version of the relationship is imagined, in which rejection inverts to nutriment, “milk pours from the sky,” “the countryside is comfortable and burping,” “Frank naps on the lawn / smiling” (5). Art redistributes the dynamics of the “real” relationship in a fantastic landscape; but the inversion also requires that the landscape itself will acquire the qualities of bodily vulnerability which attach to Frank: “with tomorrow’s sun / gutters will / curdle and / sour.” Even Art’s improvised, counterfeit consolations have an expiration date.

Art’s counterfeit reality is the space in which Frank improvises an inverted existence; another poem in which the Mother “hollers” at him for pretending to be a bird, concludes:

he pecked bugs off the ground

the rooster led him

behind the hen house (6)

The improvised dynamic of Frank’s fantasy life also allows him to participate in an alternate morality, a happy seduction/exploitation at the hands of “the rooster.” The definite article here is important: Frank is the asphyxiation casting these other personages from his own trashy material. The rooster is “the rooster,” the one commanded by Frank to appear and molest him, rather than “a rooster.” In Art’s (and Frank’s) double world, the poles of agency and victimhood are not as clearly separable as they are in the brightly lit nation to which we pledge allegiance each morning in the schoolroom.

Just as CAConrad’s own biographical sketch gestures towards a complicity in exploitation, so there is an unstable complicity in these poems between Frank and his parents. The mother, we learn, enjoys cartoonish double vision, a vision that allows her to see “the devil in every room / twirling his asshole / cooking small rodents / masturbating in Father’s E-Z chair” (8). This vision frightens Frank when he assumes it by stealing his mother’s eyes; but this very action allies him with her, allies violence and vision. Frank, after all, has similarly violent or obscene visions; in some poems Art converts violence to a violet, or magically saves a life, but in others, violence and the violence of rebirth in Art continually restates itself:

Mother breaks Frank’s paint brushes

forces his head

through canvas

“FRAME ME!” he shouts

“FRAME ME! take the copyright

from God! FRAME ME!” (19)

Here violence is constitutive; like asphyxiation, here Mother-Art is violence, she gives birth to Art by forcing his head through canvas, forcing him in and through an artistic medium, a medium she is also destroying in this act — that is, trashing. Yet Frank is the son of asphyxiation; death-giving-as-life-giving; he converts the violence to a violent self-iterating phrase; he asks to be remade as Death’s son, as Art’s son — that is, as Art. “FRAME ME!” he shouts three times, that magic number.

While the Mother and the Son struggle to birth and rebirth Art, the Father is cartoonish in his inability to fix value on his son; he first misreads his son as a cunt-less daughter, then becomes confused:

Father was confused

which was Frank?

which the five

dollar bill?

the pornographer’s smile

s t r e t c h e d

the room (11)

In the perverted stakes of the Book of Frank, even the witch-like Mother can’t fix Frank’s bodily form; nor can the Father fix his economic value. Instead Frank enters into another arrangement; the pornographer’s approval is a welcome, is a source of wealth; acceptance as a sexual commodity stretches the room, makes a roomy place for Frank. At the same time, Frank defines himself in terms of a total abnegation of value, a willing expenditure akin to his identification with miscarriages which paradoxically produces milk from the sky:

“when I die” Frank prayed,

“I will never return

if I must

it will be as

abortions

it will be as if I had not” (17)

Here the declaration that “I will never return” is met with an implicit command to return, just as he returns again and again to The Book of Frank itself. As his relationship with his mother emblematizes, the relationship to Art is in fact a commandment. The blank space in his utterance counters his own utterance, so he next tries to erase himself by voicing overstatement, a paradoxical multiplication of negation: “it will be as / abortions / it will be as if I had not.” Resourceful under Art and Life’s commandment, Frank improvises a “likeness,” an “as if” which reinvents himself as a negative infinity (“abortions”) even as Art forces him to be reborn and reborn in these poems.

As Art’s son, Frank has a nimble relationship with Death, crossing its borders, as he himself is Death. The book is riven with motifs of crows and carrion eaters; “when Father died / Frank was found / straddling him / his crows picking the seven / gold fillings” (31). This recalls Chelsey Minnis’s invocation to Death in Poemland, which is also a willingness to be bodily remade as a dead thing, as Art:

I am a vile baby …

Look, death, I have so much delicious vulture food within my chest cavity … (28).

In Poemland as in The Book of Frank, to be Death’s baby is to be Art’s baby; to be Art’s victim, but also its food; the way it comes into the world; to give birth to the Art that gave birth to you; to be a vessel and what comes out of the vessel; to be continually shedding something, Art, even as Art sheds the Artist, makes a son out of impossible non-ingredients. No value could cohere in a non-system like this, a backbreaking, self-digesting, self-gestating, cutting, immolating, imbricating system, certainly not the values of self-authenticity, self-sameness, self-worth, certainly not the value of self-expression, rendered here a complicated ventriloquist’s script of quotations and self-quotations:

“I love us with the wig,” Frank said

“it makes our voices change

you wear the wig

and ask my lips

to find you in the dark

I wear the wig

and track you

with my tongue

the wig uncombed!

the wig a fire of curls!

‘the wig completes the head?’ you ask

‘the wig completes the head’ I say” (62)

So the Artist born of Artifice, Asphyxiation, Violence and Death wears Death’s wig and scripts Death’s lines; plays the (false) role of Death; has incestuous sex with Death; trashes the “natural” body, the “natural” family, the “natural” timeline; dwells in paradox; in limitless negativity that does not reverse itself to become a positive; but sons; “one night / the dog / dissolved / with Frank,” […] “Frank with child / at last!” (116-117); generates artifice and perversion, counterfeit and copies; an ouroboros of exploiters and exploitation which blots out conventional economies of worth and value; a radiant black horizon of expenditure where the voice makes a fake voice of the voice; where multitudinous, queer, perverse, or misanthropic voices fuck up the family romance; “a room full / of lesbian / ventriloquists / threw their voices”(Frank, 80); anachronism, marginality, deprivation, violence and pettiness; but a radiant wig, a wig on fire!:

It is like being slapped in the face with a stack of dollar bills …

I like it like glitter drums! (101).