'Writing is a body-intensive activity'

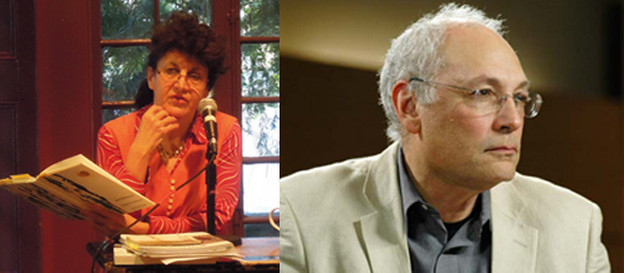

Close Listening with Maggie O'Sullivan

Editorial note: Maggie O’Sullivan (b. 1951) is a poet, artist, editor, and publisher. She is the author of over fifteen books, including Concerning Spheres (1982), A Natural History in 3 Incomplete Parts (1985), States of Emergency (1987), Palace of Reptiles (2003), Body of Work (2006), and most recently ALTO (2009). She also edited the anthology Out of Everywhere: Linguistically Innovative Poetry by Women in North America and the UK (1996). The following has been adapted from a Close Listening conversation recorded on October 11, 2007, at the Kelly Writers House at the University of Pennsylvania. The conversation was transcribed by Michael Nardone and edited by Charles Bernstein. Listen to the audio program here. — Katie L. Price

Charles Bernstein: Welcome to Close Listening: WPS1’s program of readings and conversations, presented in collaboration with PennSound. My guest today, for the second of two shows, is Maggie O’Sullivan. Maggie O’Sullivan’s most recent book is Body of Work, which collects a wide range of her poetry from the time she was living in London to after her move to the northwest of England, where she lives now. On today’s show, O’Sullivan will be answering questions from Penn students, and we are recording this on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania at the Kelly Writers House. My name is Charles Bernstein.

Maggie, welcome back to Close Listening.

O’Sullivan: Thank you, Charles. I’m really glad to be here.

Student: Thank you for your reading, Ms. O’Sullivan. I was wondering if you could describe the relationship between performing your work and writing it.

O’Sullivan: Well, it depends on … every situation is different. Performing it is another opportunity to reengage with the text at different levels and another opportunity to negotiate the text on the page. As you’ve probably heard, I often find my work is quite difficult for me to read from the page. Writing it, I hear the sounds often in my ear. But having to perform it, other difficulties emerge. There’s lots of disconnectiveness and disjunctiveness that is working against how sometimes it seems it may be read.

Student: Would you consider performing it to be more body-intensive than writing it?

O’Sullivan: Writing is a body-intensive activity, totally. Absolutely, totally. The whole body is engaged in the act of writing, whether it’s on the computer, or with using a pen in the hands. The breath is involved in all activities. But with the performing, there are others that you have to connect with, and the place of performing also figures on it.

Student: A number of your poems integrate different languages, musical notes, pictures, and streaks, and they push the possibilities of poetic forms on the page. I was wondering whether this is supposed to conflict with the words, complement them, or maybe even both.

O’Sullivan: The words working as part of all this kind of radical shifting —

Student: Right. Other forms on the page that would not be considered part of the traditional poetic form.

O’Sullivan: Well, it’s all material on the page. The page is like a score, like a place for painting, or drawing, or word-making, whatever. And I’m seeking to extend the range of poetic, what is traditionally regarded as poetic material.

Student: How do you determine which poem should be accompanied by which sort of visual form?

O’Sullivan: Well, I don’t, see — in a section of A Natural History — I don’t perceive a division between the words and the visual. The words are the visual form, and the visual form are the words. There isn’t a division for me. I don’t think of them as being separate. They all cohere in the making of the object, this construct, the composition that is, for me, the poetic text, the poetic work.

Student: So they function as one?

O’Sullivan: As one, absolutely. And I often tend to regard my works as compositions, compositions that gather in all possibility, and all possible materials: sonic, oral, textual. It’s all one fabrication.

Student: Each of your poems looks, feels, and sounds different. I was wondering if you would say whether your work resists themes at all?

O’Sullivan: Whether my work resists themes? Mmm … [Laughs.]

Bernstein: What’s it about? It makes no sense to me! There can’t be any themes there, it’s just a lot of words and pictures, eh? Eh?

O’Sullivan: … Well, there are concerns and preoccupations behind each different work. Researches, my readings, all kinds of areas are played with and brought into question for each different work. That kind of area of investigation will often declare its own kind of materials, although I think it’s not really … I don’t know what thematic means. It’s meaningless to me.

Student 2: Kind of along the same lines, as we go through your book Body of Work, we see you become more and more visual and abstract. Could you talk about your evolution and personal development as a poet?

O’Sullivan: That’s a very large question.

Bernstein: Maybe she hasn’t evolved. She’s devolved.

O’Sullivan: Evolution is a very scary word. Perhaps I’m devolving. Or spiralling.

Bernstein: Spiralling is good.

O’Sullivan: Spiralling is more appropriate, I think, to how I feel, what I’m engaged in.

Student 2: You read an early poem today, “Malevich.” How does it feel to look back on those earlier works?

O’Sullivan: I find them very exciting because, to me, they were written thirty years ago when I started out. Coming back to them, I find that I see them as a basic text. They’re inviting improvisation. Perhaps they’re inviting me to use the experiences and the procedures and processes that I’ve been using for thirty years. When I go back to them now, I approach them with all that, and so I want to read them, I want to sound them out differently than the composition appears on the page. I find there’s a lot of very surprising newness. Those early poems still surprise me, and I find that really exciting. There are things there that I’m still astonished by.

Student 2: So you find new things in the old, kind of like a recycling?

O’Sullivan: Absolutely, yes.

Student 2: And about one of your techniques, I noticed you like to underline. Could you talk about that, because you seem to do it quite a lot, and I was interested?

O’Sullivan: Well, I suppose I like to give some kind of visual notation on the page as to how deep the word might be incised on the page and how loud it might be read in performance. So I use capital letters a lot. I now use italic font as opposed to standard … and bold, using the different appearances of words and letters to give some indication of how they can be taken out and expanded. When I did a lot of this work, I worked at the BBC and I used to type scripts out, and they had certain kinds of format procedures for typing scripts. Say, for lighting, they would use lots of underlining and slashes. I really loved this, and I brought that into the making of my poetry.

Student 3: I wanted to go back to what you were talking about where the visualization of the poem — not just the writing, but how it’s all laid out on the page — all seems to come from one place. So, looking at a piece like “POINT.BLANK.RANGE.” which was comprised of photographs and drawings and graphics, when you put something like that together, does that also come from the same place where you are writing?

O’Sullivan: It comes from where I’m working, I’m not sure writing, but where I’m making and constructing. When I did A Natural History in 3 Incomplete Parts — well, I did the first section, which is like text, and then I imported a lot of materials that were around me from journals and newspapers. They seemed so necessary to the area that I was working in, and I felt their integration with the text was really vital for the kind of manifestation of the text I was working on.

Student 3: In the reading that you had just done, I loved the rhythms that you put into the readings. Have you done work with musicians?

O’Sullivan: I have, yes. It’s not so integrated. I’ve read pieces and we’ve collaborated in a very loose way: me reading and perhaps a violinist or a saxophonist playing in and out of each other. Not really very long collaborations.

Student 3: In Natural History in 3 Incomplete Parts, you devote an entire page to, like, an introduction to three senses: sight, touch, and sound. And when you’re reading this page, as I was reading this page, I felt completely just inundated with all of this language, you know, hitting you all at once. Some of the things that you talk about are primal feelings and very elemental feelings. Words like daddy, fire, clinging, breath. So how did you decide on the order of all those words and the associations to build this kind of tapestry, and what did you want the reader to walk away with?

O’Sullivan: I can’t say what the reader will walk away with, that’s up to the reader.

[Laughter.]

Bernstein: But we don’t know either! We want you to tell us!

O’Sullivan: Well, I can’t tell anything. I’m not into telling.

Bernstein: Oh, all right.

O’Sullivan: I can only say and show. I was using lots of different vocabularies, natural history, for the composition of that piece. And a lot of it was an improvisatory making. I just went, went and typed and typed and typed and typed, and a lot of the words are half-words or one-letters. I typed so fast I made lots of what might be considered mistakes in traditional spelling. But wonderful new words, new sounds formed.

Student 4: I noticed that the earlier works were done with a typewriter, and the later ones were done with a computer. I was wondering how that affected your writing process, and how you think it might affect the way we look at it.

O’Sullivan: Well, I can’t say how other people look at it. I’ve always loved the physicality of making, working. I loved working on the typewriter. I had an old, “Mal-uh-VICH” as Charles says —

Bernstein: What do I know? By the way — you’re listening to Maggie O’Sullivan on WPS1’s Close Listening, and we’re talking with Penn students here at the Kelly Writers House.

O’Sullivan: Well, that poem —

[Laughter.]

— that poem, which will be nameless, was done on a portable manual typewriter. It was about the first typewriter that I ever had. It looks quite rigid really. I love the effect that different typefaces can produce. Then I went onto a “golf ball” electric, which I absolutely adored and hated to part with.

Bernstein: The IBM Selectric typewriter.

O’Sullivan: I loved that one.

Bernstein: A milestone for —

O’Sullivan: I love typewriters. I’ve had great relationships with my typewriters as many writers do. You get so attached to them. Even though they’re out of date, you still want to hang on to them.

Bernstein: Often better relationships than with the people that surround us, I find.

O’Sullivan: And you spend more time with them than you do with people.

Bernstein: And they’re more responsive to our needs as writers.

O’Sullivan: Absolutely. And they often see you … they’re there when you are at your worst, most grumpiest, most horrible to know. They’re faithful. And very, very forgiving. [Laughter.] I’m obviously working on the computer now, but I do a lot of my work by hand, preparatory to working on the computer. I love the physical working and making words on the page. I love writing. I use different colored pens when I compose. And I still do the old basic sort of cut and paste. It’s really hands-on, tactile stuff, but I really like that. And I don’t use the computer until I get to quite an advanced stage in the composition. I’m not sure how people react when they see the differences. I love books and I love the printed page and I love the computer screen, too. But sometimes it’s a little bit distant, the computer screen … the encountering of the text. I like more intimacy.

Student 4: With the computer, you can backspace. I reckon that’s really interesting.

O’Sullivan: You can backspace?

Student 4: As opposed to on a typewriter, where you create something and it’s there, it’s on this sheet.

O’Sullivan: Yes.

Student 4: Even if you try and wipe it out, it was there. Professor Bernstein, in his forward to your book, wrote about how you like the topic of voicelessness in space, and I was wondering if you would like to talk about that … and silence.

O’Sullivan: And silence, yes. I love muteness. The page is a huge, deep, profound space to engage with, and I am trying to mine this in my workings. Although today, the pieces that I read were very rhythmic, quite full-on sound. There was not so much silence or muteness in them. But muteness, the other side of the vocal, is really important to me. And I think there is a lot of silence. I think my work is profoundly embedded in silence. In not being able to sound, sounds are coming through.

Sarah Dowling: I was wondering if you would mind speaking a little bit about the anthologyOut of Everywhere that you edited. It was very important for me, discovering a lot of innovative women writers. I was wondering, specifically, if you could talk a bit about the editorial process and where the idea for a transnational anthology came from.

O’Sullivan: Yes, well, it was a kind of collaborative suggestion from Ken Edwards, the publisher of Reality Studios, and Wendy Mulford, the co[publisher]. I think it came at a time when, in Britain — well, there are still not so many experimental writers, very, very few — but there were enough doing interesting work to be, kind of, to be displayed. And so many of us, the ones who were there, connected with North American and women experimental writers. We felt it would be really timely and appropriate to celebrate this and to see our connections and to really celebrate the connections, the conversations we were having. So, I had to leave out a lot of writers, unfortunately. There were so many more I could have had. But the point was to at least signpost this, particularly, you know, to the British community, to signpost this amazing work that was happening, and this kind of transnational discourse.

Dowling: If you were to do another anthological project now — ten or eleven years later or whatever it is — what are some of the conversations or axes that you would want to signpost today?

O’Sullivan: I don’t think I would want to do an anthology. [Laughter.] Anthologies can be … well, I think there is so much happening now. The whole terrain has changed since Out of Everywhere really radically. There is much more interdisciplinary work going on, much more activity between different genres of writing. And obviously, well, it’s so whole, where do you start? African writers? I think that I wouldn’t want to do an anthology again. I wouldn’t want to be … there’s so much available now with the Internet, I would find it a little bit restricting for me, because there are so many huge areas.

Bernstein: In the first of the two shows that we did, you read a long section from A Natural History in 3 Incomplete Parts. Could you say something about the origins of that work and some of the sources of it?

O’Sullivan: The sources? I lived in the city when I composed that: a very urban existence. I felt I wanted to try and find out more about the natural world, and how there could be some conversation between that and the urban life that I was living. I used lots of dictionaries, particularly on insects, and also books on war, on military equipment, because it was a time of huge political crises at that time in England with the government we had, the Thatcher government. So there was a huge discrepancy between my yearnings for some kind of natural world, creature existence, with the kind of Greenham Common protests and the American air bases in England, and I was trying to bring these together somehow.

Bernstein: Following up on Sarah Dowling’s question on your anthology, the collection of women’s poetry, can you talk a little about your relationship to women writers in particular? Why you wanted to do an anthology of women writers, or perhaps your experience of being a woman and a poet, and how that may affect your work or the reception of your work? This is my classic question. I always try and find a different way to ask it. I like to ask that question to men, too.

O’Sullivan: To men?

Bernstein: Yeah. Actually, we had a wonderful Russian poet on the program a while ago, and he was stunned when asked what is it like to write from the point of view of a man, and he was silent for quite some time. He said he had never thought about that.

O’Sullivan: Well, I don’t know what it is, this. I’m trying to get beyond gender.

Bernstein: Are you succeeding? [Laughs.] Can you share with us some of the, kind of, how-to? [Laughter.]

O’Sullivan: I can’t. I can’t. I see myself as a poet. Well, not even as a poet, as working with materials. I really don’t —

Bernstein: Well, are you a northern British poet? Or are you just a regular English poet? Because you live, I understand, what I learned from Steve McCaffery to call the West Riding of Yorkshire. Northwest England, that’s not quite the same as living in the southeast, right?

O’Sullivan: Well, there are too many labels there, Charles. I think I would like “poet,” if anything. And everything that I do is embraced by “poet.”

Bernstein: And within the field of poetry, there are many different kinds of poetry. Would you think that the differences … from your point of view, how would you talk about the different approaches that people take to poetry? Do you think that quality is a concern, that you can say one poet or one kind of poetry has a higher quality than others? Or even poems of your own? How do you think about the issue of quality?

O’Sullivan: Quality? What do you mean by quality?

Bernstein: Quality as opposed to genre. Do you feel that some poems are better than others? Obviously you like some poems more than others, but is the issue of quality a significant way that you differentiate between poems?

O’Sullivan: Are you talking about my work or —

Bernstein: Well, both, actually. Both in terms of your own work, individual poems of yours, but also in terms of other people’s poetry.

O’Sullivan: Well, I’m not sure what quality means. There are poems that resonate, that pose a lot of questions for me, and difficulties that excite me and can be potentially dangerous and necessary for my practice. I hate to say quality, but it’s that kind of thing. Something that speaks, that is an invitation for me to go further than where I am now, I guess. Is that quality? [Laughter.]

Bernstein: You’ve been listening to Maggie O’Sullivan on Close Listening. The program was recorded on October 10th, 2007. Our engineer is Mike Hennessey. I am Charles Bernstein, close listening for the s-s-s-sounds of s-s-s-soaring sh-sh-sh-shards and the s-s-sattering/sh-shattering/s-s-sattering/sh-shattering s-s-s-sensation/sensations of s-s-s-sense.