Kirsty Hooper's 'Writing Galicia into the World' as co-savoir

In post 13, when I spoke of Blanchot and translation as a step outside time, I briefly mentioned UK critic and Galician literary scholar Kirsty Hooper. Her landmark book Writing Galicia into the World is also a step outside time, one important to translation in a critical sense and in a wider optic. Its mission is other, but it opens up the stakes of translation itself, in a way that is co-incident with, and that has learned from, ideas of writers such as Édouard Glissant and Gilles Deleuze. Her work allows us to look anew at what it means to cross the borders of language, and better understand literature’s role in this crossing.

To tweak from the press website[1], the book’s “key theoretical contribution is to model a relational approach to a nation’s cultural history, which allows us to reframe a culture often dismissed as peripheral or minor as an active participant in a network of relation that connects local, national and global.”

The exciting thing is that it opens many possibilities to future investigators, and not just to those who study Galician culture (though, please, folks, do study Galician culture!). Hooper’s work is also co-incident and co-intuitive with ideas such as Anne-Marie Losonczy’s “cosavoir,” or “co-knowledge,” a current influence on the production of Quebec poet Chantal Neveu and others.

Hooper’s conclusion resonates: “Writing Galicia is, and could only ever be, the first step in a much bigger and hopefully collective project.” Among the pressing questions she realizes still need to be addressed: “is the question of the alófonos, those writers who publish in Galician even though it is not their native language.” “Many of their works… share a spatialized view of cultural identity, which is played out in the geopoetical frameworks they create.”

This to me is the stakes of translation played out in another way, for translators too enter as allophones, non native speakers, into a language and culture, and bear the seismic risks of their move, their bearing of that language back into their own. A generosity prevails, but the move can also cause fractures. Translation can be a kind of fracking, if we’re not taking care.

Articulations based in analysis and comparative research in literature, history and philosophy such as Hooper’s and Losonczy’s provide essential thinking for translators, as well as for critics. Spatialization, indeed!

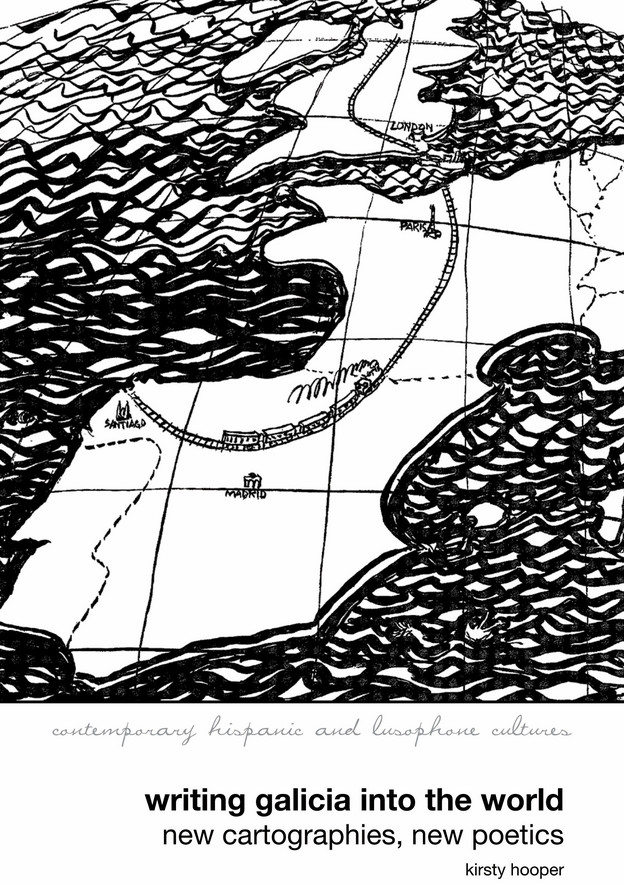

Hooper, further: “The value of the maps, the co-ordinates, the networks of relation considered in Writing Galicia lies in their potential to address not only the community of Galician readers, but outwards, transforming the ‘very conditions of possibility’ of the other reading communites of the Spanish state, but also—potentially—of the English-speaking world.”

“Ultimately,” she ends, “the power of the readings that emerge lies in their dynamic interaction with the multiple networks of relation which, in the words of Éduoard Glissant, are ‘not prompted solely by the defining of our identities, but by their relation to everything possible as well—the mutual mutations generated by this interplay of relations.’” This interplay is relentless and beautiful, and affects our ongoing relationship to translation into English, creating new, contiguous spaces for writers and critics to explore.

[1] which really says: “Its key theoretical contribution is to model a relational approach to Galician cultural history, which allows us to reframe this small Atlantic culture, so often dismissed as peripheral or minor, as an active participant in a network of relation that connects the local, national and global.”

T r a n s l a t i o n ' s__H o m e o p a t h i c__G e s t u r e s