The Tarzan method

In working last week with translator and writer (and multimedia, book designer and theatre guy) Daniel Canty on his current translation in progress of Little Theatres as Petits Théâtres, I remembered the original inspiration for the wee bilingual Galician-English dictionary at the back of my theatres. It was my childhood Whitman Classics edition of Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan of the Apes. No wonder that I’d always been drawn to translation!

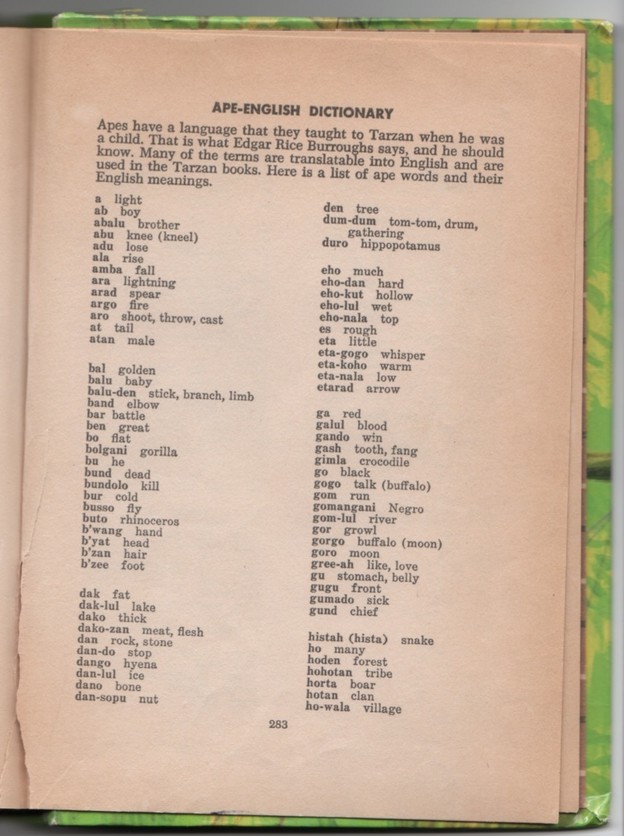

It was, perhaps, my 11th year, and as a Christmas or birthday gift, I received a copy of the book, a copy I had to share with my brothers. It was the rule of books. At the back of the novel was something I’d never seen before, and it intrigued me: a bilingual dictionary. Ape-English, three pages long. I tried to use it to write poems in Ape but the words were limited, rather violent, and there were no connectives. As well, I had to read all three pages of English words before finding one I could use, as the dictionary went in one direction only.

Years later, when I knew the time was coming when we would be called to help my father move out of his house, I spotted the book on a shelf there still, and asked him if I could have it. He said, no, it belongs to your brothers. And I said, no, it was given to me! He disagreed. I gave up. But I told my father that there was something beloved in that book, a three page Ape-English Dictionary. He said there was no such thing. I told him, oh yes, and I loved it so much that when I had to share the book with my brothers, I wanted to keep the dictionary for myself, and decided to hide and tear it out of the book. An evil act. As I started to tear the paper, I felt horrible, and stopped. There was a 5 c.m. jagged rip in the page; I patted it flat and shut the book, hoping no one would notice, no one would realize that the tear had been deliberate.

My father looked at me strangely. He took the book off his shelf and looked at the back, for he remembered no such dictionary. He arrived at the page you see above, looked at me again, and held the book out to me. It’s been a precious possession since.

And not just for the dictionary. Something even more important happens in the story, I think: The young man Tarzan teaches himself to read a language he does not know, using children’s books he found left in the ruins of his own parents’ house in the jungle. By looking at images and letters over and over, he learns to read English. This reality stuck with me, and when years later I wanted to learn Galician, I did it at first on my own, buying workbooks forchildren and reading them over and working through them until I began to understand. And working through the same workbook over and over, understanding a bit more each time. I call it the Tarzan Method of language learning.

I’ve had other help learning Galician, of course. But I owe thanks to Tarzan that I can translate Chus Pato and Rosalía de Castro today.

T r a n s l a t i o n ' s__H o m e o p a t h i c__G e s t u r e s